By SARAH LURIA and DANIEL JACKSON

Houghton Garden (Fig. 1) was created in 1906, on the grounds of an estate in Newton, Massachusetts, owned by Martha Gilbert Houghton and her husband. Houghton hired Warren Manning, a leading landscape architect and former member of Frederick Law Olmsted’s studio, to work with her on a design for her garden. Manning disliked the kind of formal garden fashionable at the time, which subdued nature with symmetrical, geometric forms. He advocated what he called a “nature garden,” whose design was less invasive, and took advantage of the elements nature already provided. This demanded, as he put it in an essay quoted by Robin Karson in Nature and Ideology (1997):

… a new type of gardening wherein the Landscaper recognizes, first, the beauty of existing conditions and develops this beauty to the minutest detail by the elimination of material that is out of place in a development scheme by selective thinning, grubbing, and trimming, instead of by destroying all natural ground cover vegetation or modifying the contour, character, and water context of existing soil.

In How Fiction Works, James Wood provides a “primer” along the lines of John Ruskin’s The Elements of Drawing, in which Ruskin, as Wood says, “cast[s] a critic’s eye over the business of creation.” In the process of photographing Manning’s nature garden, we find some tangible evidence of the realist’s “business” as she or he creates a world for another inhabitant.

Manning’s starting point is to recognize and appreciate what exists, rather than to create ex nihilo. This strategy calls to mind photographer Minor White’s goal, as stated in his 1951 American Photography article, to create “a feeling the photographer imposed nothing, but instead let the subject matter itself generate, dictate and determine the composition out of its own shapes and relations.”

Figure 1

Figure 2

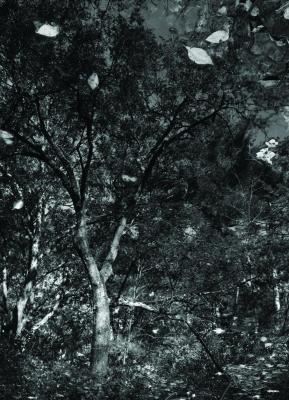

Manning created his gardens not by replacing what existed with new forms, but by “selective thinning and grubbing” (digging up roots and stumps), by eliminating material he felt to be out of place. Photographer Stephen Shore, in an interview with Michael Fried, describes his own process in similar terms: “The metaphor I have in my mind is that in a certain way I am clearing the space for the viewer.” Both Manning and Shore select, but always in order to heighten a sense of the natural. As Henry James puts it in “The Art of Fiction”: “Art is essentially selection, but it is a selection whose main care is to be typical, to be inclusive.” We might say that both Shore and Manning achieve that blend of “artifice and verisimilitude” that James Wood extols in fiction where “there is nothing difficult in holding together these two possibilities.” Like Manning, Shore highlights what he most appreciates in what is already there, by “clearing,” “pruning” or “selecting” within the space—not literally by any explicit manipulation, but by a selection of camera position and angle that brings order and balance to an otherwise apparently chaotic scene.

Both Manning and Shore use the place that already exists, and from it, frame views for their observer. Houghton Garden itself exists as a series of such views (Fig. 2). At the heart of the garden is a pond, framed by rhododendron bushes, that acts like a window to the worlds beyond and above. We look down into the water’s surface and see the sky, as well as something that lies beneath. The pond’s view acts as both mirror and window, gesturing beyond itself.

In a similar way, the panes of the triptych of photographs (Fig. 2) form a window framing the main ingredients of this nature garden—just water and trees—and so emphasizes (or as Manning might say, “develops”) the effects of enclosure and expansion created by these natural elements. Henry James noted that the realist author always produces not “reality” itself but views of it, which are “as nothing without the posted presence of the watcher—without in other words the consciousness of the artist.” In other words, the realist always shows “reality” as seen, and the reader is aware of looking at the scene only indirectly, over the shoulder of the author. The photographs of the pond capture not just the pond itself, but the pond as we imagine Manning and Houghton wanted us to see it. By taking this view, we hope to add another generation to the process of seeing, so the photograph becomes an image of an image, like a collection of Russian dolls, or the nested photographs in the filmMemento.

Looking at, rather than into, the water, we see how Manning and Houghton played with the garden conventions of their day. A favorite feature of Olmstedtype gardens was a series of spatial reservoirs or outdoor “rooms.” Like a foyer, with its carpet of leaves, the garden’s pond takes us deep into the interior beyond (Fig. 3).

Figure 3

But Manning and Houghton were not interested in incorporating built architecture, such as we see, for example, in the stair and tunnels of Central Park’s Bethesda Terrace. Instead, Houghton Garden takes its structure from nature. Leaves run wall-to-wall and floor-to-ceiling, building out the space, the same materials used in contrasting clumps and planes. By selecting and pruning, Manning and Houghton bring out nature’s own remarkable floorplan.

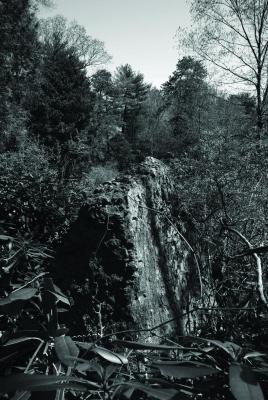

The trail guide to the Houghton Garden lists it as a 0.4-mile walk, and yet as we follow along its path with its smooth carpeted floor (Fig. 4), we have the feeling we could go on and on through an endless burrow of paths, nudged this way and that by the bush walls. The paths are sheltered and enclosed, little halls through the foliage that let us see only a little ways ahead, and this paradoxically creates a sense of greater distance since we never know exactly just how much further we have to go.

Along the path, wedged between path and pond, we come across a surprising rock (Fig. 5). Framed just so, sandwiched between the rhododendron leaves in the foreground and an array of trees behind, it gains stature. The relative size of the trees is hard to gauge: tall and distant or small and close? The result is an optical shift between close-up and long view that makes us unsure of just how big the rock face is. The image again highlights the idea of nature as seen, which, in contrast to nature itself, dictates the design of the garden. This reminds us of how photographers have always reveled in illusions of scale, whether serious, as in Paul Caponigro’s apple, whose surface might be the star-flecked sky of the entire universe, or humorous, as in Eliott Erwitt’s birdon- lamppost-meets-airliner, or Lee Friedlander’s road sign that is topped with a cloud as if it were an ice cream cone.

At the same time as it subverts them, this garden of natural surprises fulfills our conventional expectations—our mental pictures of what such a garden should look like. We expect to come across a bridge (Fig. 6) not just because of the central part water plays in the garden, but because every charming garden needs a little footbridge. Here perhaps Manning’s conceit of a garden made by nature belies the human needs imposed on it. If we really wanted to take nature on its own terms, maybe we should be content to get our feet wet.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

But the romance of the bridge is irresistible, for landscaper and photographer alike. However modern and jaded we may be, most of us have a side that is more Ansel Adams than Robert Adams, that wants not a deeper reconciliation with the flawed beauty of the world, but an escape into a more perfect world.

Yet for all these romantic and idealistic desires, the bridge is only allowed to play a minor role; at Houghton Garden, nature always dominates. The wrought iron fence that surrounds the garden pales in comparison to the trees (Fig. 7) that tower over it and enclose it in a majestic curtain. The branches crowd together, and yet the structure remains light—its weight distributed evenly across the sky, the strong trunks helping balance and anchor the airy web of branches and leaves.

Figure 7

In looking at and photographing Manning and Houghton’s garden, then, we see the game of realism in play. Authors like Henry James and Edith Wharton abhorred the idea of obviously manipulating their characters like puppets on a string. Instead they claimed their characters appeared to them; the realist author’s job was simply to watch and record what, given a particular situation, such characters would do. The power of such fiction comes from its accuracy of observation, its receptivity to human nature, its insight into the interior of our lives. The Olmsted-Manning type of nature garden was so successful because it predicted with such accuracy what its characters—its plants and trees and landforms—would do, how they would evolve over time. The conceit is that nature is the best architect, but the success of the garden confirms that, in fact, Olmsted and Manning are the best architects: “nature’s garden” would not exist without them. So too, for all James and Wharton’s professed modesty—we’re just the scribes for our characters!—their authorial presence and genius in novels likeThe Portrait of a Lady or The House of Mirth loom large.

We return on our walk through Houghton Garden almost to our starting point by taking a different path, one that follows not along the edge of the pond but rises along an outcropping of rocks. We look in the same direction as Figure 3, but what a difference an elevation of 20 feet has made: our cozy room has become a renaissance Eden (Fig. 8). In realist gardens, as in novels, point of view is everything. Though we walked the two paths, the contrast between these two views was not clear to us until we saw the photos. Sometimes we need to photograph, and write, the world just to see what it looks like.

Figure 8

Sarah Luria co-edited Geohumanities: Art, History, and Literature at the Edge of Place and is the author of Capital Speculations: Writing and Building Washington, D.C. She teaches American literature at the College of the Holy Cross.

Daniel Jackson is a photographer working in Newton, Massachusetts. His most recent work includes a study of the Chestnut Hill pumping station, and may be found online at http://straightphotography.org. He received his degrees from Oxford University and from MIT, where he is currently professor of computer science.

[Purchase your copy of Issue 02 here.]