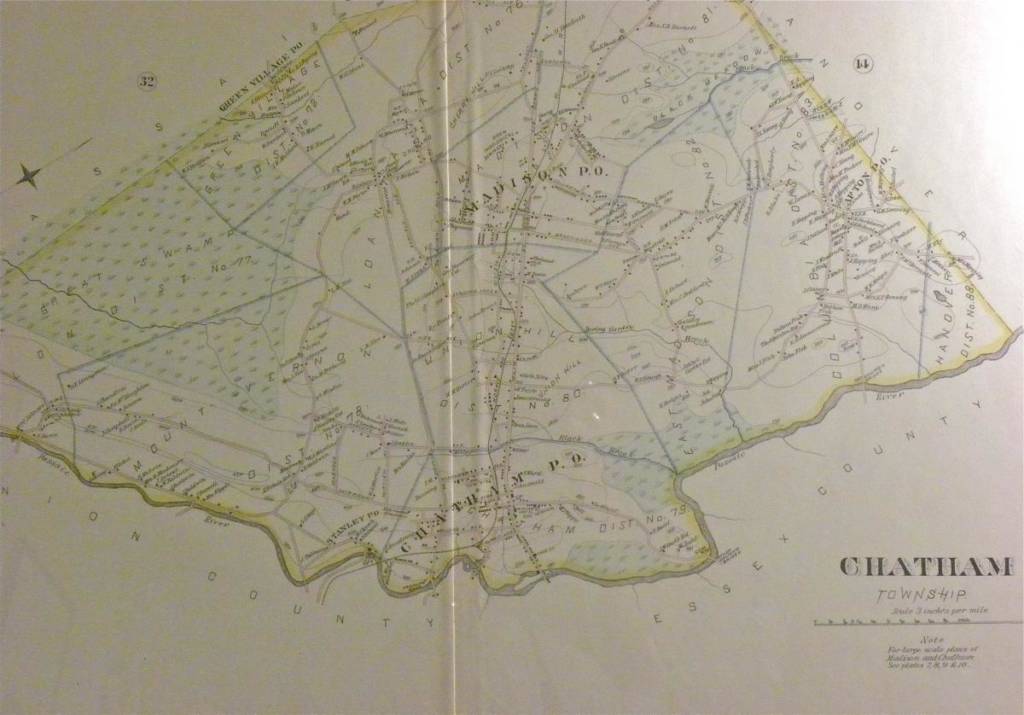

For a gardener, geology is destiny. My little bit of earth is in a town surrounded on three sides by water. Chatham, New Jersey, sits at an elbow of the Passaic River that forms its northern and eastern boundaries. To the south, the so-called Great Swamp soaks vast acreage. Yet for all of its perimeter liquid, the town is built on rock.

The Passaic’s riverbed is carved along the base of Long Hill, the third and last of the Watchung Ridges, a set of basaltic vertebrae that runs roughly north-south. Long Hill, christened “Fair Mount” by early Chathamites, forms the backbone of the town. From just three steep blocks uphill from my house, one can gaze over our little valley and imagine the waves of prehistoric Lake Passaic lapping up. A bit of the old lake still finds its way into my garden.

In a residential development project now dotting Long Hill, heavy equipment has uncovered a layer of sedimentary rock the color of New York City brownstones. Stone for those Italianate terrace houses of the mid-1800s was quarried here. Millennia earlier, dinosaurs waded in the lakeside mud that morphed, over time, into these rocks. My agreeable husband helped fill the back of the Subaru with several loads of this ochre-brown rock, which we turned into an edge and path for a new garden bed.

You wouldn’t think that we’d need to import rocks into our garden: Stick a shovel anywhere in the backyard, and you’ll be rewarded with a clang. Our property sits along the east-west moraine, the stopping of point of America’s last glacier. A thin veneer of soil, mostly reddish clay, covers the collection of stone that the ice sheet amassed in its trek southward through Canada and New England. Many of these stones are rounded, worn by the emery action of the moving ice.

My favorite of these glacial hitchhikers is Roxbury puddingstone, a purple conglomerate with a name like an English dessert. We constantly scout construction sites, numerous during the most recent teardown era of Chatham’s geological time, and liberate any choice specimens unearthed during excavation. The best of these now provide structure for a collection of tiny hostas along the back walk.

Out of other rocks chosen for their squarish shoulders, we’ve built a low wall along the wooded back property line. It’s homage to the colonial farmers who cleared this land for pasture and orchard and field. They would be horrified to see the reforestation that a few generations of suburbanites have managed to achieve. When Hurricane Sandy toppled a white oak in the back corner of the lot I mourned the loss of the tree, but I rejoiced in finding a good-sized piece of sandstone among its massive roots to add to the wall.

The leaves from the trees on our property get composted every year, offsetting to a degree the heaviness of the clay soil. In the nineteenth-century, Chatham boasted a thriving brick industry, but the clay pit that was once a source of raw materials is now an astro-turfed athletic field. Still, clay laces the local soil, and clay and stone make for heavy digging. Each year when I plant the latest batch of daffodils with the inevitable clank of rock on tool, instead of cursing I smile the smile of a petrophile.

Marta McDowell is the author of Emily Dickinson’s Gardens, published by McGraw-Hill in 2005, and her book on Beatrix Potter’s gardening interests is due out from Timber Press in October 2013.