Artist: FRANCES STROH

“I realized these were all the snapshots which our children would look at someday with wonder, thinking their parents had lived smooth, well-ordered lives and got up in the morning to walk proudly on the sidewalks of life, never dreaming the raggedy madness and riot of our actual lives, our actual night, the hell of it, the senseless emptiness.”

― Jack Kerouac, On the Road

When I was sixteen my father gave me a Nikon FM for my first high school photography class. He’d look over my shoulder at the B&W prints scattered cross our dining room table—portraits of white Goth faces dripping with black eyeliner, studies of peeling urban walls in abandoned tire plants, and Hari Krishnas—and he’d invariably say, “Yep. You’re a better photographer than I am. Keep it up!”

I shot the images in early 1980s urban Detroit, or in some friend’s basement in our leafy suburb of Grosse Pointe. My father’s support meant everything to me then, particularly since his talent as an amateur photographer was widely recognized among our friends and acquaintances in the Detroit area, where our family had been brewing beer for four generations.

His parents had discouraged him from attending art school and photographing professionally, pushing him to join the family business; yet he’d kept shooting film throughout his life. But an artist without a champion is like a runner against fierce headwinds, and he never had the confidence to show his images in a public context.

Now, revisiting my father’s body of work six years after his death, I realize my photographs never held a candle to his vision of suburban Detroit life in the sixties and seventies. My images are reflections of typical teenage forays into the redemptive unknown: Detroit’s abandoned manufacturing plants; the urban punk rock scene; the post-riots decay. My father stuck to what he knew: casually staged portraits of his family and friends in their lush gardens, houses, and clubs—portraits that often arrived as signed cards at Christmastime. And yet today his images hold up as artifacts of a very particular, now bygone world—the rarified sphere of Midwestern industrial wealth.

Grosse Pointe’s wide, tree-lined boulevards, lakefront estates, and classic country clubs were home to all the automotive company founders, such as Henry Ford, and their descendants. My own family made Stroh’s Beer, a Midwestern brand that supplied the automotive workers with tasty, cheap brew, and later went national to compete with Anheuser Busch and Miller. Throughout the twentieth century, the wealth in Grosse Pointe was staggering. The grand old estates along the waterfront were erected as summer houses for Detroit industrialists who’d built the city from the ground up. After WWII, Grosse Pointe became a full-time sanctuary from the heavily polluted inner city and, by the late 60s, from racial tensions.

The 1967 riots created an irreversible trend of white flight from the city to the suburbs. While in the 50s, Detroit had boasted the fastest growing black middle class in America, by the 70s the poverty and segregation had grown to unprecedented levels. The automotive industry was slowly moving out—to the suburbs and abroad—draining the city of its tax base and leaving a mostly destitute population in its wake.

I remember my father instructing my brothers and me to lock our doors as soon as we crossed into Detroit on Jefferson Avenue. It was well known that the Grosse Pointe police escorted black pedestrians from our side of the Detroit border back to an increasingly derelict and underserved inner city. Coleman Young (Detroit’s mayor from 1974–1994) who called himself the “MFIC”—Motherfucker In Charge—encouraged Detroit’s segregation from its suburban counterparts, only making matters worse.

Increasingly disconnected from its urban center, Grosse Pointe became a haven of conformity. Stepping beyond the established bounds of fashion was rare, with personal style manifesting as little more than a cautious flourish: penny loafers with dimes, a bracelet snaking around a slender upper arm. It was Lilly Pulitzer and Brooks Brothers by day, black tie by night. And as a nod to the local industry, everyone drove American cars to work downtown, reserving their sporty European cars for the weekends.

My father’s images capture the apparent ease with which his subjects inhabited their world: what Ta-Nehisi Coates calls “the gorgeous dream.” The leisure life, the good life—the dream that America promised us all, but delivered to only a few; the dream that hides from any suggestion of its own falseness. And yet the world recorded in my father’s images is one that sits on the brink of its own unraveling. Soon the decline in the American automotive industry, the plummet in Detroit’s real estate values, and even the precipitous loss of market share for my family’s beer brands would portend what was in store for the rest of America: outsourcing, multinationals, the blight of the rust belt, rampant unemployment.

My own photography in the 1980s recorded the aspects of my world where irreparable fissures had already appeared—the city itself, and a narrow sampling of its various subcultures. The decay in Detroit felt more real, more honest than my daily reality in Grosse Pointe. And yet I see now that my father’s images, with their blithely detached subjects, were far more authentic than my own. He recorded what he knew, redemptive or not. His subjects have gentle, confident smiles—smiles that evoke that palpable sense of boundlessness and invincibility in the post-war era, when it seemed everything was possible. And yet the innate pathos of “the gorgeous dream” cannot be denied in these images; they affirm our blindness, our assumed exceptionalism. Indeed, our American-ness. We were Detroiters, after all—living on the fumes of America’s industrial greatness on cruise control, and headed for the wall.

The jobless in Detroit continued to live in an urban center with a rapidly dwindling middle class, the highest murder rate in America, and, as if to give voice to its woes, a burgeoning punk rock scene. Everything that had made Detroit great—Motown, abundant jobs, home ownership, and the fastest-growing black middle class anywhere—was vanishing into history.

Which is exactly what makes my father’s photographs compelling. They recorded a time and a place like no other, and its populations’ unique sense of separateness from the other world just a few miles down the road. Doors locked, Grosse Pointers drove their sleek American cars to only the most privileged spaces in Detroit—offices in high rises, the Detroit Athletic Club, The Detroit Institute of Arts—avoiding the sprawling slums. Privilege, it seemed, was a beacon in the encroaching night. And yet the impulse to separate and insulate was not unique to Grosse Pointers. There were also the well-heeled suburbs of Bloomfield Hills, Birmingham, and Troy. Indeed, all across America, wealthy neighborhoods butted up against blighted areas, yet nowhere to the extremes experienced in Detroit.

And it was these extremes toward which my father and I gravitated. While my father remained an amateur photographer throughout his life, I hoped to fulfill his destiny myself by becoming a professional photographer. But in my 20s I went on to become an installation artist in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and eventually London. “Get out that camera once in a while, why don’t you?” my father would say. And I would get it out, but by then it was a video camera, and I would be shooting footage for my installations. Later, when I became a writer, my father supported me by simply asking, “Can I be a character in your great American novel?”

Photography was about freezing things in time to better understand them. Narrative became a space for me to unfreeze, to breathe life back in, and to connect the dots in a new pattern. And it was my need to reconstruct what seemed fixed, both in my father’s images and in my own memory, which compelled me to write my slice of the American story as a memoir. My father gifted me a camera, in the beginning, but more importantly, the courage to brave those fierce headwinds. And along the way I learned to record what I knew, and, little by little, to find my voice.

Digging through the stacks of boxes that contained my father’s unseen photographs, I wondered how many voices have recorded the American story but never been heard; how many boxes sit in attics and closets across our nation, concealing versions of our collective dream; how many voices have been silenced by a lack of resources, a dearth of support, or a belief that one’s vision is of no importance. On Detroit’s Cass Corridor, or in the depths of Louisiana’s swamplands, in my own streets of San Francisco they lay hidden, I knew, these slices of the Dream.

And as I uncovered my father’s work, I wondered how his singular vision had fallen between the cracks. Had he grown up in Chicago or New York, where a far more extensive gallery and collector network existed than in Detroit, might things have been different for him, career-wise? In the spirit of collaboration, I resolved to take his images out into the world—as the visual component of the chapters in my memoir, and in a myriad of other ways. Soon, I told myself, this unknown voice will ring out, telling an important slice of the American story, frame by indelible frame.

Family of Seven, 1973

Girl on Tennis Court, 1977

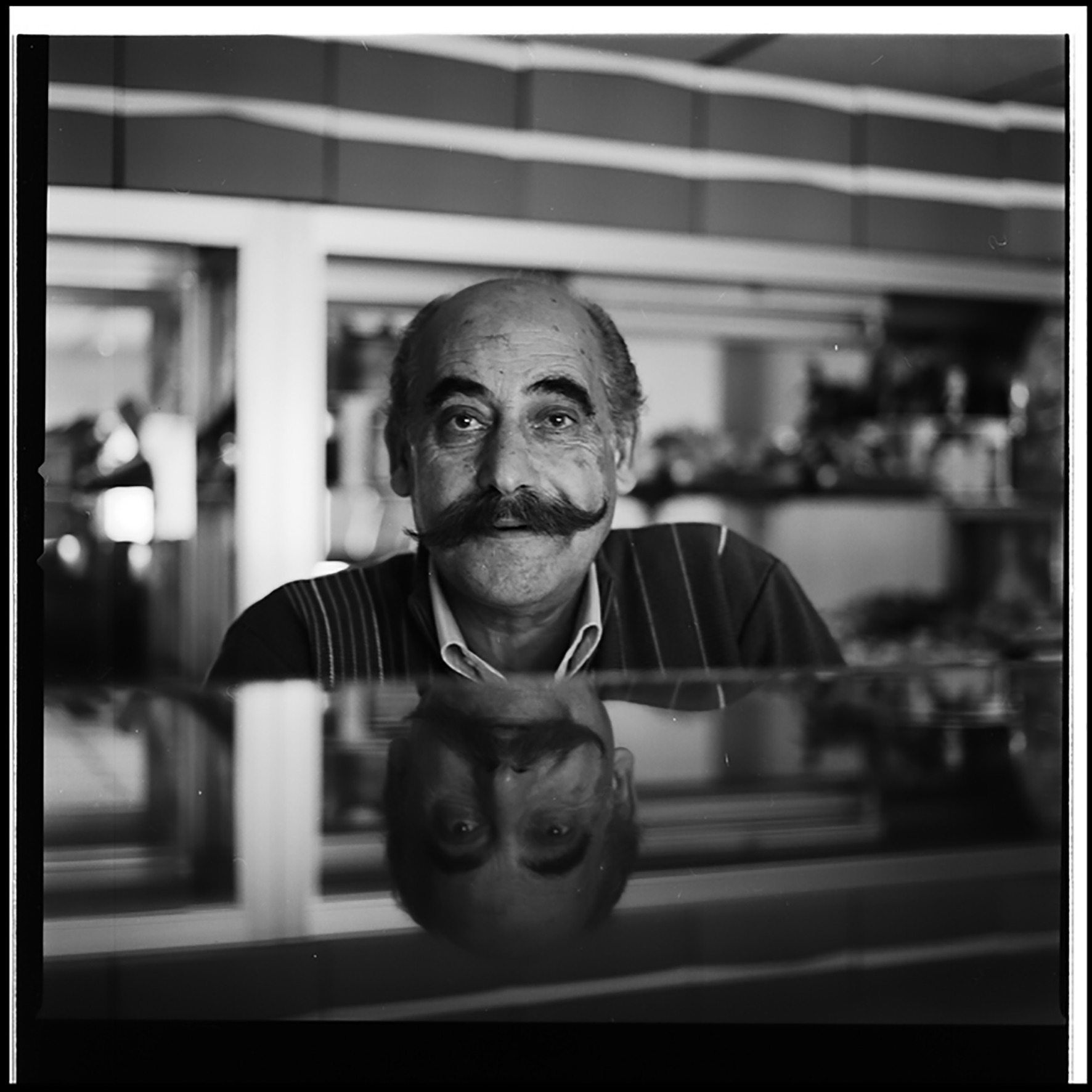

Eric Stroh Self-Portrait, 1978

Stroh’s Beer Party, 1962

Woman with Cat, 1974

British Racing Green, 1976

Mother and Child, 1967

Frances Stroh was born in Detroit and raised in Grosse Pointe, Michigan. She is a member of the San Francisvo Writers’ Grotto, and her work across all media explores issues of identity, point of view, and the mythologies that define us. Her forthcoming book, “Beer Money: A Memoir of Privilege and Loss” will be out on May 3rd.