Translated by LISA MULLENNEAUX

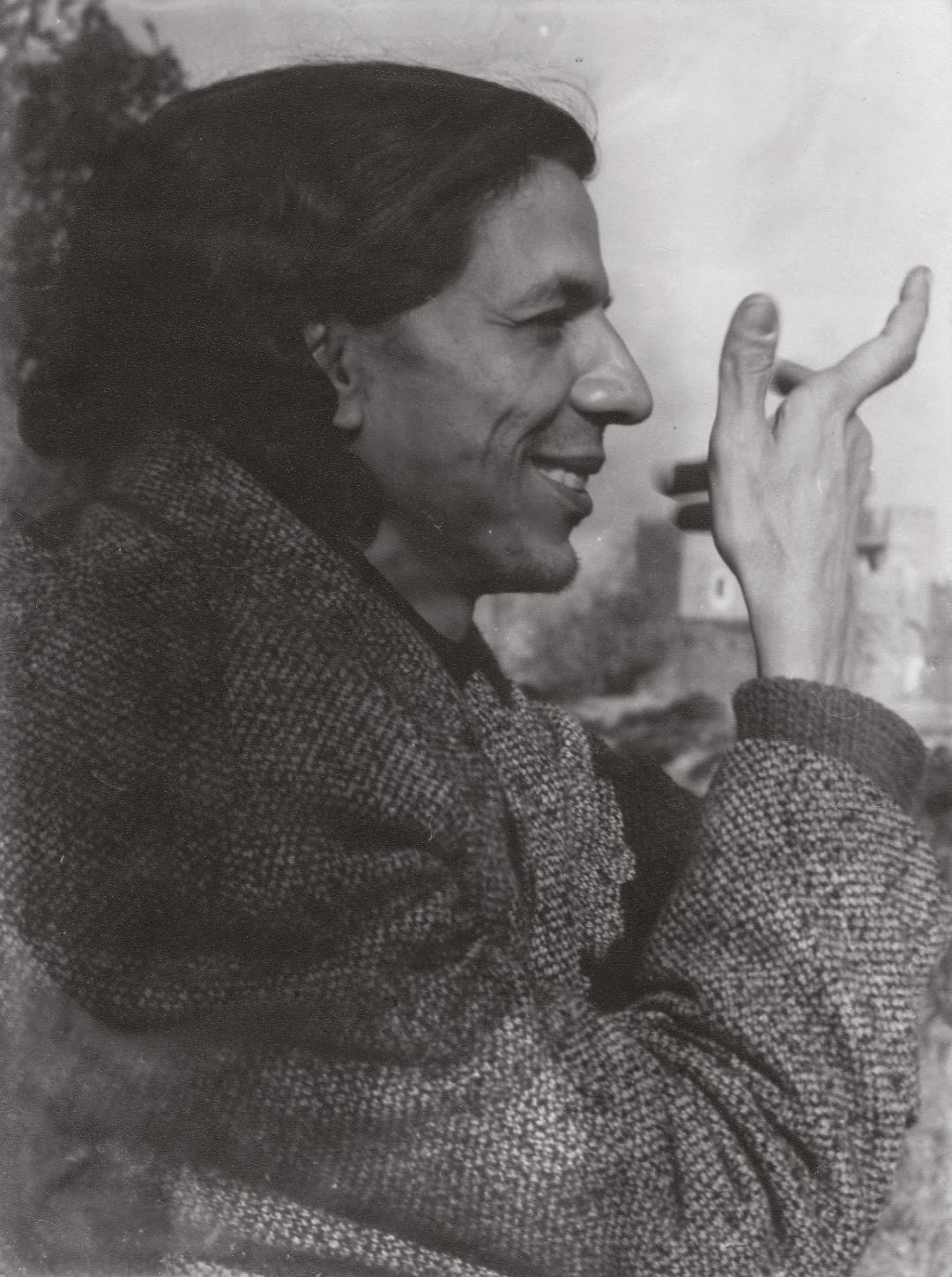

Photo courtesy of Archives Bouanani

This country

My country is this horizon with blank pages

where I see skeletons of broken children

wandering, begging for the light of thin wisps

of stories that might finally appease them

In hands the color of amaranth magic

they hold hippogriffs like dogs

a talisman to protect themselves from the lover

with hair braided into black shapes

All evening every evening until old age

under the ocean of sky under the constellations

they will come to shed the blood of their distress

and celebrate their death in sad ablutions

My country where ancestors with pagan joy

marauded in songs and paradises

Their white horses drank from a thousand fountains

of sanctity and love Who would have told us

Was it the March wind or their poems

War ships had destroyed their horizons

so appalling hypocrisies could triumph

Our bestiary deserted our homes

Horsemen of the past facing our windows

still speak to us about the lights of the fields

and living legends that gave birth

in our breasts to strange setting suns

Ce pays

Mon pays est cet horizon aux pages blanches

J’y vois errants des squelettes d’enfants brisés

mendiant sur des lumières de maigres tranches

de contes qui pourraient enfin les apaiser

Entre leurs mains couleur de magie amarante

ils tiennent des hippogriffes comme des chiens

un talisman pour se protéger de l’amante

à la chevelure tressée de noirs desseins

Les soirs tous les soirs et jusqu’à la vieillesse

sous l’océan du ciel sous les constellations

ils viendront déverser le sang de leur détresse

et fêter leur mort en tristes ablutions

Mon pays où les ancêtres aux joies païennes

maraudaient dans des chansons et des paradis

Leurs chevaux blancs s’abreuvaient aux mille fontaines

de la dulie et de l’amour Qui l’aurait dit

Etait-ce le vent de mars ou leurs poésies

Des destroyers avaient détruit leurs horizons

pour le règne d’effroyables hypocrisies

Notre bestiaire déserta nos maisons

Les cavaliers d’autrefois face à nos fenêtres

nous parlent encore des lumières des champs

et des légendes vivantes qui faisaient naître

dans nos poitrines d’étranges soleils couchants

Wild Miniatures

I was born in the kingdom of false memories

in the margins of long-forgotten manuscripts

While elsewhere soldiers drunk on looting

raised bloody garrisons on the mountains

camels and dogs gone wild

cheerfully trampled the horizons

Soon there was no one in the villages

except old men old women and little kids

The dying men called the storms

The old women sang of new tomorrows

War famine then war again

and the amnesia of many generations

as in dawn dreams as in Gomorrah

where plantations have long since died

Kids in the heart of torrid autumns

buried Satan the angels and the seasons

Their ghostly features cracked with wrinkles

they vanished above new houses

I was born very early there and learned to believe

that angels left us on the doorstep of latrines

left us to our pitiful history

the only orphans unworthy of antiquity.

Miniatures sauvages

Je suis né au royaume des fausses mémoires

en marge des manuscrits longtemps oubliés

Tandis qu’ailleurs les soldats ivres de pillages

dressaient sur les monts de sanglantes garnisons

Les chamelles et les chiens devenus sauvages

piétinaient allègrement les horizons

Bientôt il n’y eut personne dans les villages

que des vieux des vieilles et des petits gamins

Les vieux agonisant appelaient les orages

Les vieilles chantaient de possibles lendemains

La guerre la famine puis la guerre encore

et l’amnésie de plusiers générations

comme dans les rêves d’aube comme à Gomorrhe

où sont mortes depuis longtemps les plantations

Les gamins eux au coeur des automnes torrides

enterraient Satan les anges et les saisons

Leurs traits fantômatiques lézardés de rides

s’effaçaient au-dessus de nouvelles maisons

Là je suis né très tôt et j’ai appris à croire

qu’au seuil des latrines les anges nous quittaient

pour nous laisser à notre pitoyable histoire

seuls orphelins indignes de l’Antiquité.

The filmmaker and writer Ahmed Bouanani (1938–2011) was born in Casablanca. When Bouanani was 16, in the final days of the French colonial era, his father, a police officer, was assassinated, a tragedy that the artist returned to in his work again and again. Bouanani studied film at the Institut des hautes études cinématographiques (IDHEC) in Paris for three years before returning to Morocco, where he directed several classics of North African cinema. He published three poetry collections during his lifetime, as well as the novel The Hospital. Bouanani’s generation of artists and intellectuals were persecuted and tortured by King Hassan II’s government for celebrating a national culture long suppressed by the French. The poet honors “the ancestors,” “the horsemen of the past” and their oral traditions over the king’s official history. Given the imprisonment of his fellow poets, Bouanani was reluctant to publish his written work and was known mainly for his films, yet they, too, were censored.

Lisa Mullenneaux specializes in the translation of modern French and Italian poets, such as Louis Aragon, Maria Attanasio, Alfonso Gatto, and Giovanni Giudici. She also reviews books in translation for the Harvard Review, Women’s Review of Books, and World Literature Today. She is the author of the critical study Naples’ Little Women: The Fiction of Elena Ferrante and has taught research writing for the University of Maryland’s Global Campus since 2015. More at lisamullenneaux.com.