NAYEREH DOOSTI interviews ALEKSANDAR HEMON

Aleksandar Hemon is the author of the novel The Lazarus Project, which was a finalist for the 2008 National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award, of which Junot Diaz said: “Incandescent. When your eyes close, the power of this novel, of Hemon’s colossal talent, remains.” Hemon has also written three books of short stories: The Question of Bruno; Nowhere Man, which was also a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award; and Love and Obstacles. His autobiography The Book of My Lives, was also a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award. Hemon was the recipient of a 2003 Guggenheim Fellowship and a “genius grant” from the MacArthur Foundation. Born in Sarajevo, Hemon visited Chicago in 1992, intending to stay for a matter of months. While he was there, Sarajevo came under siege, and he was unable to return home. He now lives in Chicago with his family.

A week after the release of the January 27 executive order titled “Protecting the Nation from Foreign Terrorist Entry into the United States,” The Common’s editorial assistant Nayereh Doosti talked with Hemon in the library of the Lord Jeffery Inn during his visit to Amherst College. Their shared perspective—growing up outside the U.S.—and the ban’s direct effect on Doosti guided the conversation toward the intersection of politics and literature.

*

Nayereh Doosti (ND): I met you at the Bookstan Festival in Sarajevo this summer. You spoke a lot about the rise of Trump, and at some point I could see some non-Bosnian faces looked very confused or uncomfortable because the focus of the talk had shifted to politics, as if politics and literature are two completely separate entities. But all good literature is more or less explicitly political. And I know this is your mantra. Can you talk about your view of the state of politics in contemporary American literature?

Aleksandar Hemon (AH): It’s a very complicated question. To use novels to make a political impact is not necessarily the only or the best way. Because it takes a long time to write a novel. It takes a long time to publish it. It takes a long time for a novel to reach the reader. But at the same time, I think each writer and each novel has some kind of ethics, whether they acknowledge it or not. Some ethical vision of the world, an ethical concept of what human life and human beings are. To be aware of the ethics in one’s own work, to own it, is political.

In some ways the novel is in fact the longest-lasting way to establish a political and ethical position in the world and in a public space. Because writers are also public individuals; they have access to the public space. For me, ideally, I’d use both the novel and the public space. I wrote an article about Trump that pertains to last week’s events, or whatever, the inauguration, and I expect it to vanish. I hope that it won’t be relevant ten years from now, five years, two years. Its perishability is accepted. Whereas a novel, a story, an object of art should last regardless of specific political realities.

ND: In a recent article, you suggest the rise of Trump may rescue American literature, if “a good writer never lets a catastrophe go to waste.” This is what you do in your work, which always deals with both American and Bosnian politics and history. But to me, it seems as if that’s easier to do in retrospect. When one is directly affected by the catastrophe, the shock may make it almost impossible for the writer to confront the “unimaginable realities.” So the writer uses her work to resort to alternative realities. What is your “prescription” for writers in such conditions?

AH: [Laughs.] Well I don’t write prescriptions. A prescription is some sort of an ideological demand that I would not put upon others, and would not want anyone to force upon me. But at times of historical, societal ruptures (and I think we’re in the middle of one, because Trump is already destroying something and it’s just started and we’re paying a terrible price), the destruction is already ongoing, and that is the destruction of reality that many people have taken to be self-evident and solid and stable. So all you have to do as a writer is to address it and then interpret it creatively. This is the current fate of the realistic concept of literature where your work as a writer or your book is diagnosing society.

Because this country has been stable in some ways and for a certain class of people, and now it’s falling apart, some of the novels written five years ago, in many ways, are no longer applicable. They’re either complicit in creating an image of society where the problems are simplified, or the conflicts are simplified or reduced to the exclusive experience of a certain group of people. It’s a widely generated fiction of the American Manifest Destiny, and decency in America, that guarantees consumerism and the pursuit of happiness and all of that. Or they just seem like novels of the last century. It’s all just shit now. It has to be questioned from the beginning. So to me, to own the destruction, the rupture, is to accept the fact that this country is not what we thought it was, whoever we may be.

In other words, Trump is an absolute and total failure in American society, including its literature and culture and art, and politics, and democracy, and everything! And he’s been only two weeks in office so far, so the literature has to address this to some extent, otherwise it’s complicit and propaganda. And I expect it to happen. Because what else are we going to do?

ND: Historical evidence shows that good literature thrives under political and societal restraint. In a way, and as ironic as it sounds, the rise of [Slobodan] Milošević helped your own writing flourish. Do you see parallels between Trump’s nationalism and Milošević’s? Or do you find such comparisons problematic?

AH: There is no absolute parity between the two, or equality in their methods—so far at least. But nationalism, like many ideologies, has its common traits, common methodologies. There is a similarity between Milošević and Putin, and Milošević and Marie Le Pen, and not because Milošević invented [nationalism], though he was one of the best in the 20th century and post World War II. Because there is a political pathology to nationalism, the same modes of operation repeat, the same tropes and the same ideological constructs and so on. I could talk about it all day long. For instance, nationalism tends to be a masculine operation. Men carry the nation, women generate citizens who will die in wars for the nation. [Laughs.] Wherever you see nationalism of that kind, on the cusp of being outright fascism, in Russia, Serbia, Croatia, the United States, wherever, it’s always rampant sexism. In that discourse, the nation is conceptualized as male.

Another trait: the insistence of the purity of the nation; the nation is presented as contaminated by “some foreigners.” It used to be the Jews, who were among “us,” or among “them,” and somehow they contaminated the purity of the nation. [Jews] were crossing borders and to shut down the borders was essential to the purification.

Another thing, and this is the most common one, is the ideological move when the people busy themselves with finding traitors and the contaminators. This is what happened with Milošević too: establishing an economy depended on genocide and nationalism, from which only a thin layer of the elites took advantage or benefited.All these symptoms I’m familiar with. And it’s not just me; everyone from Former Yugoslavia who is not a fascist himself or herself can see it. As a matter of fact, Serbian nationalists recognized the kinship and supported Trump openly, and that made a big difference I think in Ohio, where there is a substantial Serbian population. In addition, there is the possibility that Trump has some kind of notorious connection with Putin. They’re of the same ilk, they belong to the same society. They see the world the same way, even outside of this nationalist bullshit. They think the same way about women and homosexuals and Muslims and so on.

ND: I want to go back to what you said about the writer’s responsibility. I think a similar sense of responsibility could or should be expected from translators. When it comes to translation, and politics of translation, the paradoxes of life and political realities are standard expectations from literatures of the so-called war-torn regions. Once it was the Balkans, now the Middle East, and the list goes on. This is how the popular American readership (and society in general) focuses on the problems of the “other” and deliberately forgets how miserably its own literature is divorced from politics, or how lacking its literature may be; this is especially a phenomenon in American translation. This is all happening when, as you suggest, there is no novel that discusses the inequities of the post 9/11 era. The farthest fiction on this subject went was to discuss “how difficult it was to shoot innocent people in the head.” Do you think the narrow focus of American translation plays a role in the gradual decadence of American literature?

AH: It’s improved a little perhaps, but not much. As a reaction to 9/11 and post-9/11 American nationalism, there are certain parts of the publishing industry that renewed interest in “other parts of the world.” But literature, any literature that is supposed totranslate “other” works is by necessity provincial. It does not communicate with other literatures, with other aesthetics, and ethics for that matter. The American publishing industry suffers from something that I like to call metropolitan provincialism; that is, the belief only in things that are “of value.” In other words, all that needs to be known is already known or will be soon known.

I remember when Patrick Modiano won the Nobel Prize, his work had never come out in New York. (I think the only translation at the time was from Yale University.) People were essentially claiming, well if he was any good, I would have known about him. And this is bizarre to me. I think that’s what has damaged American literature, has been damaging it for decades. At the same time there are people, and not just writers, publishers and critics too, who are fighting against that. There is substantial Spanish-language publishing activity in this country. Spanish language literature, rural literature in Spanish, especially from Latin America, has had a major impact on North American literature. It’s not so visible in the elite circles of New York necessarily. But in certain parts of the world, and in this country where people speak Spanish in cities, they have a major role. For instance, Junot Diaz cannot be fully understood outside of this context.

ND: On the topic of translation, I want to ask you about the experience of being translated into your mother tongue. I know you didn’t translate The Making of Zombie Wars yourself, and by doing this you somehow suspended your authorship and maybe even “alienated” yourself from the Bosnian readers. Why did you choose not to translate the book yourself and what was that like?

AH: I work with my Bosnian translator. She’s been my translator since The Lazarus Project, and she’s very good. She allows me to edit and supervise, so she writes a draft and then I edit it, and then I adjust it; so I’m not really alienated from that. If there is an alienation it’s because, for example, I’m writing about Chicago and certain tropes about Chicago are more accessible to someone who reads English routinely than someone in the world of the Bosnian language.

People ask me all the time if I’m a different person in different languages. I’m not. Not any more than I’m a different person in the same language when I talk to my children, and when I answer questions from a smart young journalist like you. People have different registers in different contexts. I do not step into a different world when I speak Bosnian. What’s different is the referential system. Psycholinguists may or may not think differently, but I think when we speak different languages, we’re the same person; it’s not a different world.

Years ago I translated some of my stories, but they were terrible translations. After the book was published I discovered that they were just not good, that I was misusing Bosnian words. And some of the sentences had English syntax and were clunky in Bosnian. For instance, in English, you use the same word, “camp,” for “concentration camp” and a “tourist camp.” Whereas in Bosnian it’s not the same word, ever! Camp is only for tourists, whereas the word for concentration camp is “koncentracioni logor.” I used “kamp” for concentration camp, because to me it was the same thing. In Bosnia it sounded like a bad joke to say “koncentracioni kamp.” Because it conflates fascism and tourism. [Laughs.] And there were other instances like that, and I thought, with greater discipline I could have done it. But I’d have so much work. [Laughs.] Since then I let others translate. I have the utmost respect for translators. It’s a heroic endeavor to translate. It’s incredibly creative, but also an incredible responsibility.

ND: Let’s finish by talking about the role of place in your work. Your writing, much like Joshua in The Making of Zombie Wars, much like yourself, traverses between languages and between places, between Sarajevo and Chicago, between Bosnian and English. How does this constant movement between the two realms affect your writing process?

AH: I don’t think of it as moving in between. I mean, I move between Chicago and Sarajevo, but the languages overlap, the cultures overlap. For me, that’s not a traumatic experience, as some people assume. I think it offers incredible opportunity…. It’s a privilege to have a multilingual or multicultural experience.

*

Nayereh Doosti is an Editorial Assistant for The Common.

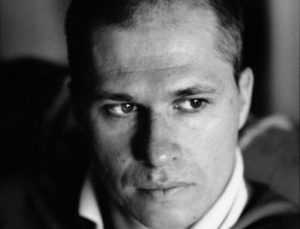

Photo courtesy of the author.