By ABBIE KIEFER

Gardiner, Maine

Gardiner, Maine

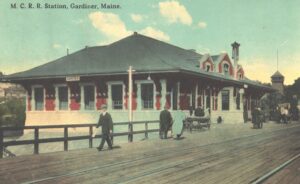

Raw granite and brick, hip roof like a helmet. At its height, it hummed: seventeen trains daily, lumbering in along the river. I imagine E.A. here with his ticket and his trunk. With his back to the brick, listening for a whistle.

Now the depot is a cannabis dispensary. They keep records in the ticket booth, make brownies in the basement. Preservationists call this adaptive reuse.

—

In E.A.’s day, Gardiner made paper: manila, newsprint, onionskin for bibles. Sodden pulp, steaming rollers. Every shift, the mill men spooling the sheets.

E.A. believed he was doomed, or elected, or sentenced to life, to the writing of poetry. His unquestionable calling. Few in Gardiner would have called that a job.

E.A. left Maine in 1897. The depot stopped service in 1960. The last mill closed in 2001. Everyone in Gardiner called it inevitable.

—

In his Pulitzer-winning collections, E.A. writes frequently about one fictional village: Tilbury Town. Its people falter against their failings, against change that won’t be stopped.

They endure or they don’t. We empathize or deny. E.A.’s lens is neither kind nor unkind.

—

Most mill buildings are gone now, knocked down or burned, but in my mind I stand them up along the river. All that paper, all those shifts. All the honest livings — none that I would have wanted.

On Brunswick Avenue, a mile from E.A.’s old house, a sign solemnly welcomes you to Tilbury Town. The sign’s one-sided, so when you leave it says nothing.

When I left, I called it temporary.

I was wrong. I was wrong about E.A. departing from the depot, which didn’t exist until a dozen years later. E.A.’s station was a long wooden shed, razed when made needless by the new, grander terminal.

I find the date of the depot’s construction just as I think I’m nearly done writing this essay. I’m frustrated — unwilling to abandon my train-station metaphor and the work I’ve done making it. From the same document, I learn that the depot’s design echoes Romanesque architecture. Medieval churches and castles — sheltering structures.

It’s a soft mirroring, a slight nod. Architects, those optimists, call this revival.

—

Perhaps the most famous resident of Tilbury Town: Miniver Cheevy, who sighed for what was not, longing for days he’s only read about. Unlike his neighbor Richard Cory, disillusioned Miniver doesn’t kill himself — but he does descend into drinking.

—

I’m reading a biography of E.A. and a history of Gardiner. I learn that Gardiner had its own brass band, that E.A.’s house had a grove of pear trees. That E.A.’s mother, Mary, died of diphtheria — a disease so strange I have to check the spelling.

My mother grieved when I told her I was leaving. We grieved in parallel, then I was gone. And what if we’d known about the coming diagnosis — shifted cells, even then, quietly colonizing. Would I have left, knowing home would be lost to me twice.

I picture the brass band, which sometimes led funeral processions. I think of Mary’s orchard, ripening in her absence.

—

E.A. lived half his years in New York, spent two decades of summers at MacDowell in New Hampshire. But his whole writing life, he returned to Tilbury. Over and over — though he always insisted Tilbury wasn’t modeled on Gardiner. Or if it was, only in a shadowy way.

In 1935, E.A. died in Manhattan. His hometown held a memorial in the high school auditorium. There were speeches and songs, a reading of “Miniver Cheevy.”

The next day they interred his ashes, brought to Maine from New York. Whoever carried them likely traveled by rail: the coupled cars steady-swaying, the landscapes gently blurring. I can see a conductor, striding the aisles, calling out the name of each station. So the riders knew, without question, when they’d reached the right place.

Note: The first and third italicized phrases are from E.A. Robinson’s personal correspondence. The second italicized phrase is from Robinson’s poem “Miniver Cheevy.”

Abbie Kiefer‘s work is forthcoming or has appeared in Arts & Letters, The Cincinnati Review, Grist, Passages North, Poet Lore, and other places. She is on the staff of The Adroit Journal. Find her online at abbiekieferpoet.com.