By KURT CASWELL

Bending to a high-power telescope trained on the moon at the McDonald Observatory in the Davis Mountains of west Texas, specifically the terminator line that is the far reach of the sun’s light at this phase—waning Gibbous moon—the contrast of light and dark makes visible the rims and floors of uncountable impact craters. My companion and I can see the crater walls, the striated lines of some long past moment of chaos, the crusted lip of the crater’s edge where the force of that energy lifted and curled into a rift of moon rocks. The sun’s light on the lunar surface is so mesmerizing along that line, so utterly beautiful, that coming away from the eyepiece, all you can see is moon.

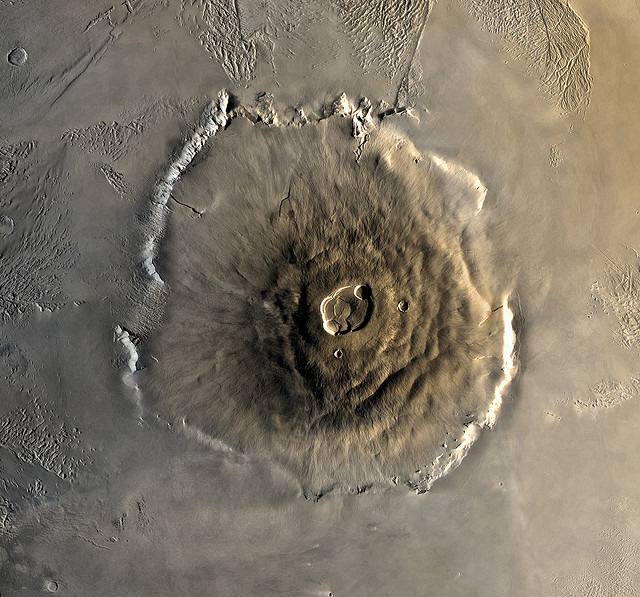

And yet those craters, as wild and deep and fantastic as they are, are little to speak of set beside the highest mountain in the solar system: Olympus Mons, on Mars. The mountain’s base covers an area the size of the state of Arizona, about 114,000 square miles. Its summit rises to nearly 85,000 feet off the Martian surface. By comparison, mighty Mount Rainier National Park covers an area of about 368 square miles, and Mount Everest stands at only 29,029 feet. Olympus Mons is a shield volcano, formed entirely by flowing lava, not unlike Manua Loa, one of the five volcanoes that makes up Hawaii, but 100 times larger—so large, in fact, that if you stood atop Olympus Mons, you wouldn’t know you were on a mountain.

Olympus Mons is but one volcano of many in the Tharsis Montes region, a vast highland desert in the western hemisphere of Mars near its equator, a desert the size of the western United States, 1,850 miles across, and all of it at the elevation of Mount Everest.

People may soon explore Olympus Mons via Mars One, a private endeavor with the goal of establishing a permanent settlement on Mars by 2023. Applications for the first four voyagers are in progress now. There are two caveats: first, it’s a one-way trip (hence “permanent settlement”); and second, participants will be filmed as part of a reality TV show. The first caveat is familiar, as it was little different for the 15thcentury sailors departing from Europe for the unknown across those vast oceans. The second is also familiar, with an exception: this won’t be reality TV, so much as it will be reality, with high-definition cameras offering 24/7 viewing of the “scientific research, experiments and exploration of Mars.”

Coming down the mountain from the McDonald Observatory under a hail of starshine and black night—the darkest sky in the lower 48 states—the universe went on expanding around us, my companion and me. We pulled into Davis Mountains State Park to camp for the night. There, under the leaf-less fingers of hackberry and ocotillo, a family of javelina, or peccary, moved ghostly by as we set up camp. Endemic to the southwest deserts, javelina mostly eat grasses, seeds, roots and cacti, especially prickly pear, but they will also eat small animals, and even attack and kill humans. They make an otherworldly chattering sound by rubbing their massive tusks together, a warning that says: stand back. We stood stock-still in the darkness as they passed, and I thought then that the fantastic is indeed way out there on the mountains of Mars, and it is also right here in this campground, on Earth.

Kurt Caswell is the author of two books of nonfiction: In the Sun’s House: My Year Teaching on the Navajo Reservation, and An Inside Passage, for which he won the 2008 River Teeth Literary Nonfiction Book Prize.

Photo from the University of Lisbon on Flickr Creative Commons