Poems by AIGERIM TAZHI

Translated from the Russian by J. KATES

Translator’s Note

For the most part, the Russian poets I have translated—however different in style and school—have been of my own generation and share many of my persuasions. How much more distant from me is Central Asia? Russian serves as a shaky bridge I cross with trepidation. But for the Kazakhstani poet Aigerim Tazhi, born in 1981 in Aktobe—formerly Aktyubinsk—Russian is solid ground underfoot. “I live in Kazakhstan,” she has said, “but I was born in the Soviet Union… I did not choose the Russian language, did not evaluate it… It’s just the language that I’ve spoken since childhood.”1

Fortunately for me, Tazhi also has a feel for English. Our collaboration (to extend the bridge) spans chasms of age and gender as well as culture, and somehow has proved remarkably productive and congenial for more than seven years now. We share a number of attitudes that inform our collaboration, most notably for the present context, a preference for letting the poem speak, and not the poet. We both recoil from injecting ourselves into the text, and from setting a poem in an autobiographical framework. This is why I publish using only my initial, and why Tazhi minimizes any personal information in contributor’s notes and other writings around her work.

—J. Kates

видишь это солнце

снегом перекрашено

в серое

веришь ли

я внутри такая же

смелая

словно ты

не смущаешь

я мир освещаю

слущая

оттенки белого

в слабость

спитого чая

(untitled)

you see this sun

repainted by the snow

in gray

do you believe

I am the same inside

emboldened

as if you

do not interfere

I illuminate the world

precipitating

shades of white

to the weak consistency

of watery tea

Косматый кактус на окне

Цепляется за тюль. Болючий

Укол в ладонь. Вдоль по стене.

Не наступить на лунный луч,

Не раздавить ни домового,

И никого ещё живого.

В новорождённой темноте

Расталкивая сны и тени,

Сесть на диване, замереть,

Как будто выключили время,

Как будто нас не ждет финал,

А мир прекрасен, только мал.

(untitled)

A shaggy cactus in the window

catches on the drape. A stinging

spine in the hand. Along the wall.

Don’t step into a moonbeam,

Don’t tread on a house-elf

Or any other living thing.

In the newborn darkness

Pushing away dreams and shadows,

Sit on a sofa, keep still,

As if time had been turned off,

As if the finale were not waiting for us

And the world is spectacular, but small.

Aigerim Tazhi was born in the western Kazakhstani city of Aktobe (formerly called Aktyubinsk) in 1981. She is a graduate of the Aktyubinsk (Zhubanov) State University. Her only book of poetry so far, БОГ-О-СЛОВ (“THEO-LOG-IAN” sort of, but there is a play on words that could come out “GOD O’ WORDS“) was published in 2003. She has received numerous literary prizes in Kazakhstan and Russia for poems in the collection, and In 2011 she was a finalist for the Russian Debut Prize in poetry. Her work has been translated into English, French, and Armenian, and published in prominent literary magazines. Tazhi was one of the creators of a project of literary installations, “The Visible Poetry,” in 2009. She lives in Almaty, Kazakhstan.

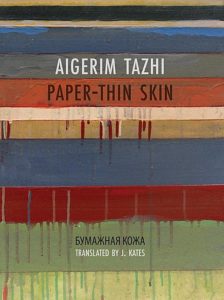

J. Kates is a poet and literary translator. He was awarded his third National Endowment fellowship for his translations of Aigerim Tazhi’s poems, since published as Paper-thin Skin (Zephyr Press, 2019).

Footnotes

1Interview with Philip Metres, translated by Philip Metres