BY NARINE ABGARYAN

(Translated from Russian by Lisa C. Hayden)

reviewed by OLGA ZILBERBOURG

A brave writer begins her novel with the deathbed. Instead of hooking a reader the way the proverbial gun on the wall might, opening with a death scene threatens her with the inevitable backstory.

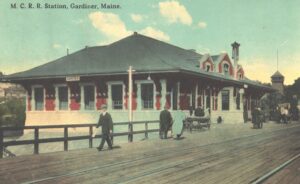

Luckily, Narine Abgaryan is both a brave and an experienced writer. Three Apples Fell from the Sky is her fifth full-length novel, which won Russia’s prestigious Yasnaya Polyana Literary Award in 2016. Maine-based Lisa C. Hayden translated this novel for Oneworld, and after a COVID19-based delay, the book was released in the UK in August 2020. The novel opens with Anatolia Sevoyants, the protagonist, as she lies down “to breathe her last.” Soon, though, we learn that while Anatolia fully intends to die, life is far from finished with her.

Gardiner, Maine

Gardiner, Maine