Artist: BEN SHATTUCK

When I first heard of the Nicaraguan Canal Project, I thought of the 19th-century artists Martin Johnson Heade and Norton Bush. It was winter, and I was driving through Wisconsin, early evening, listening to the news. The canal, the reporter said, would be three times as long and twice as wide as the Panama Canal. It would fit extra-large container ships. It might stimulate Nicaragua’s economy. Environmental groups were protesting potentially large-scale disaster.

Bleak, gray Wisconsin landscape passed by my car window. The sun was already setting, illuminating patches of roadside snow blue.

Heade and Bush had traveled to Nicaragua over 150 years ago, when it took a long time and was really hard to get there. I thought of Heade’s paintings of storm-washed rainforests. Hummingbirds gripping orchid stems. Thick foliage blotting out sunrise. I thought of Bush’s sunset on Lake Nicaragua, which he’d painted like a light-smothered Eden. When I arrived home, I bought a plane ticket to Managua.

The impacts of the $50-billion Nicaraguan Canal Project are somewhat unquantifiable, but here are the basic numbers: the route will displace over 30,000 people, many of whom are indigenous; Central America’s largest lake, Lake Nicaragua, will be silted after dredging, decimating local fisheries, the lake’s ecology, and polluting drinking water; and in a country that holds 7% of the world’s biodiversity, the canal will affect an estimated 2,500 square miles of forest, coast, and wetlands—including the San Miguelito wetlands, the Cerro Silva Natural Reserve, and the Río San Juan Biosphere Reserve, containing the Los Guatuzos Wildlife Reserve, the Indio Maíz Biological Reserve, and the Solentiname Archipelago. There have been over 35 protests since HKND—the company funding and developing the project—broke ground in December, and uproar from environmental agencies and publications, such as Nature and Yale Environment 360.

Of the many reasons for journalists to go down there, mine was art historical. I imagined that we probably didn’t need another article adding to the pile that have come out since this past winter. But I did need to memorialize the land and water itself, which is invaluable to those living on it, and significant in our art history. I wanted to render a landscape that braces itself for shock. What will be done there cannot be undone. Land, water, and ecologies will be changed.

I constructed a carrying case for painting panels, outfitted a strap for a light-weight easel, and started following the canal route. In the following weeks, I would paint a stretch of beach planned to be the site of a fuel jetty and 1,000-meter wharf, a moonrise over farmland that will be drowned by 152-square mile artificial lake, and the water of Lake Nicaragua, home to a species of freshwater shark, that will be silted. I found and painted from sites where Heade and Bush stood.

Paintings transcend language and culture. A tree looks like a tree no matter what language or culture a person knows. A lake looks like a lake. A cloud a cloud. I’d be on the roadside or hillside, and behind me, almost always, someone would be watching. In all my conversations at the easel, I never heard a Nicaraguan support the canal. Be it the farmer on the volcanic island of Ometepe who lamented what the canal would do to the water, or the hotel owner in Granada who said it would ruin tourism, or the fisherman in Brito who had been vaguely promised a fishing vessel when the wharf came, or the taxi driver near Las Palomas. “All this,” the driver said, waving his hand toward the village at the base of the hills, “will be gone.”

It would have been easier painting from photographs, in the studio. Howler monkeys dropped mangoes on me. I escaped a swarm of bees—miles from town—by running into the ocean, paintbrushes in hand and clothes on. I held my breath underwater, clutching the brushes, listening to the last of the bees embedded in my hair buzz down to their deaths. I stayed in many hammocks tied up in people’s homes. I lugged drinking water through 95-degree heat. Every day I strapped on my easel, and kept walking. Hopefully, I’ll return every year for the next ten, documenting the changes as they come.

Ometepe Island, Looking South to Dredging Area. Oil on board.

Estuary at Sunrise; Fuel Jetty and Wharf to be Here. Oil on board.

The Lake Beyond the Trees. Oil on board.

Pink Evening in Las Isletas. Oil on board.

Sardine #1, Brito. Oil on board. The fisherman who caught this sardine will not be able to fish here anymore. The rocks where he stood, and on which the fish lies, will be the site of the fuel jetty. I slept in a hammock in his house for days, painting the ocean and the beach.

From a Cave in Brito; The Exact Place where the Canal Will Begin. Oil on board. While I was painting this, a swarm of bees attacked me. I swam out into the waves – pallet, brushes, and all in hand – to get away. The sand embedded in the paint here is from leaving the easel while I tried to drown the bees. A gust of wind came, and knocked the painting onto the beach. The bees stung me all over.

Moonlight Over a Farm that Will be Under an Artificial Lake (Nueva Guinea, eastern Nicaragua). Oil on board.

Gray Day on Ometepe; Dredging Area Just Beyond. Oil on board.

Fishermen in Brito, Location of 1000-meter Wharf. Oil on board.

Wave, Brito. Oil on Board.

Bougainvillia on Farmer’s House, Ometepe. Oil on board. Like many of the people who introduced themselves to me and then watched me paint, the farmer who worked here said he opposed the canal. It will be bad for the Lake, he said.

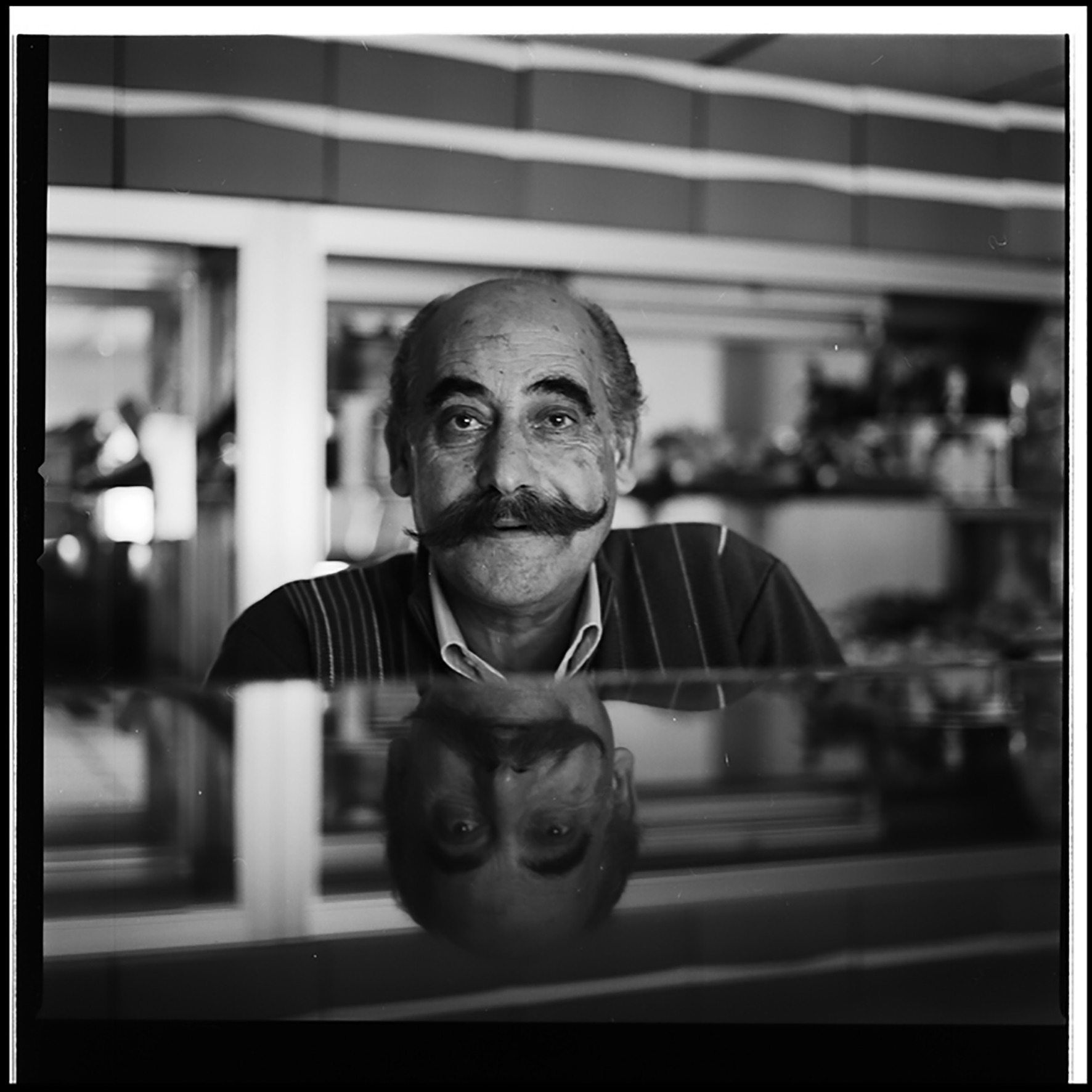

Near Lake Nicaragua, with the carrying case I constructed fort the trip. It holds thirty painting panels.

Antony Dias, of Brito (western Nicaragua), painted with me for a few days. Here, he holds up his own painting. Antony Dias, of Brito (western Nicaragua), painted with me for a few days. Here, Antony holds up his painting of three fishermen in the surf. He and his parents live in the sleepy village on Brito beach, fishing every day in the waves. From HKND canal project report: “The Brito Port would include the following facilities: North Wharf structure, 1,100 meters long, capable of supporting a 200,000 dry weight tonnage (DWT) bulk carrier or 25,000 TEU container ship; West Wharf berthing facilities, 1,200 meters long, accommodating: Three 70,000 DTW container berths; One 30,000 DTW oil /fuel jetty; 13 work boat berths; and Other miscellaneous supporting facilities.” That would be behind him.

The Nicaragua Canal paintings were exhibited at Dedee Shattuck Gallery in August. Half of all profits from the exhibition will be given to a non-profit organization that provides aid to Nicaraguan communities. The organization has asked to not be named.

Ben Shattuck is a writer and painter from coastal Massachusetts. He has written for Salon.com, The Paris Review Daily, McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, and The Morning News.