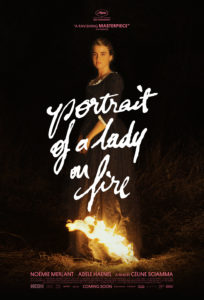

Movie directed by CÉLINE SCIAMMA

Review by HANNAH GERSEN

In 1770, Brittany, France, a young female painter, Marianne, is hired to paint a wedding portrait of a noblewoman. But the assignment is unusual: she must make the painting in secret because the bride, Héloïse, is reluctant to marry. Héloïse and her mother live in an isolated seaside estate, and her mother explains to the young painter that the portrait is necessary to entice the bridegroom, who lives in Milan. Héloïse (Adèle Haenel) is arrestingly beautiful, and I can imagine many movies that might begin with the groom’s approving gaze upon receiving Héloïse’s portrait, kicking off a storyline that would take viewers into Milanese high society. But Portrait of a Lady on Fire instead focuses on the two weeks that Héloïse and Marianne spend together in a nearly empty house by the sea (the bridegroom in question never appears on screen). Written and directed by French filmmaker Céline Sciamma, and with a nearly all-female cast, Portrait is both a romantic story of two people falling in love, and a sensitive depiction of a female painter’s life and artistic practice in the eighteenth century.

The film is framed by events in Marianne’s professional life, opening upon a portraiture lesson that Marianne (Noémie Merlant) is giving to a group of young women. One of her students uncovers one of Marianne’s paintings, which happens to be in the classroom: an arresting and possibly surreal image of a young woman standing in a dark landscape with the hem of her dress on fire. This painting, titled Portrait of a Lady on Fire is the jumping off point for the film: a recollection of a love affair.

From here, the film unfolds in flashback, and we next see Marianne heading out to her commission in Brittany, ferried by a group of fisherman in a rickety rowboat. She arrives at Héloïse’s estate carrying her own supplies and soaking wet after a rough ride. She’s greeted by a timid maid, Sophie (Luàna Bajrami), who lights a fire for her in the large room that she will use both as a bedroom and as a studio. Marianne immediately strips off her wet clothing and sits nude on the floor in front of the fire, smoking a pipe. She’s framed by the stark, empty room and lit by the fire’s golden light. In this quiet portrait, we see Marianne’s independence, as well as her comfort in solitude. It’s one of many scenes that left me with the strange desire to live in the world of this film—strange, because I don’t harbor many illusions about what it would be like to exist as a woman in the 1700s. What makes this love story so intoxicating is that it has no illusions about women’s limited options during this time period, but revels in the moments of freedom that women found anyway.

The first half of Portrait is concerned with Marianne’s covert assignment. Héloïse has been told that Marianne has been hired as a companion for walks, so during the day, Marianne and Héloïse’s hike the grounds of the estate, clambering down stone cliffs in heavy dresses and heeled boots. Marianne stares at her for as long as she can get away with, trying to memorize her face in order to sketch it later. The camera takes on Marianne’s perspective, focusing on the nape of Héloïse’s neck, her ears, her profile, and her eyes that are pale blue like the sea that roars in the background. The two women don’t talk much during their walks, even as Marianne attempts to draw Héloïse out. It’s hard to say, at first, if she genuinely wants to get to know Héloïse, or if she is just trying to elicit more information to inform her portrait. She complains to Héloïse’s mother that she hasn’t seen Héloïse’s smile. “Try saying something funny,” Héloïse’s mother advises her.

During these early scenes, I found myself thinking of a Modern Love column that went viral a few years ago, which suggested that two strangers could be made to fall in love if they stared into each other’s eyes for four minutes after asking a series of personal questions. The time that Marianne and Héloïse spend together is brief yet intimate, and not only because of Marianne’s searching gaze. Héloïse is at a vulnerable time of transition, and wrestling with a lot of anger. She’s fresh from a convent, where she had planned to live her life; the marriage was meant for her older sister, who, rather than marry, threw herself into the sea. When Marianne first arrives, there is some fear in the household that Héloïse will do the same. But Héloïse has an appetite for life; she also seems desperate for a sympathetic ear. She tells Marianne that she was happy in the convent, a place where she could read to heart’s delight and hear music every day. Marianne tries to get her to make peace with her fate, describing the orchestra music she’ll hear in Milan, but this only annoys Héloïse, who sees that Marianne enjoys her itinerant life and would not be content to marry, either. There’s a prickliness to the young women’s early interactions, in part because Marianne is guarded, and can’t reveal her true occupation, but also because of their growing attraction to each other.

At night, Marianne works on her canvas, bringing all her technical skills to bear. Portrait is unusually attentive to the process of painting, with many close-ups of Marianne’s canvas and her hands as she lays down a base coat of paint, sketches Héloïse’s face and figure, measures for the correct proportions, and examines her initial brushstrokes. Without Héloïse to pose in her formal attire, Marianne has to wear the dress herself and examine its folds in the mirror. It’s hard to tell how much time is passing, but after what seems to be a week, maybe two, the portrait is finished and Marianne reveals it—and her true identity—to Héloïse. Unsurprisingly, Héloïse is furious that she’s been lied to. She also hates the portrait—but surprisingly offers to pose for a new one. Marianne asks for an extension, and the mother, who is about to leave the estate for several days, tells Marianne that the portrait must be done by the time she gets back.

Here is where I started to creep, cautiously, toward the edge of my seat. I must admit that while the first half of this movie is visually stunning, with a rich color scheme of seaside blues and grays to contrast with warm, golden interiors, its cinematography is somewhat conventional—much like Marianne’s first portrait of Héloïse. But everything gets wilder when the mother leaves: the shot compositions are bolder, more surreal and playful. The story also expands in an unexpected direction when Sophie, the maid, admits to a personal problem that she must attend to while the lady of the house is away. Marianne and Héloïse work together to help her, a task that takes them beyond the confines of the estate. Without Héloïse’s mother around, they are finally able to admit their attraction to each other. The stilted quality of their earlier interactions disappears, and they make they most of their limited time together, spending hours in bed, talking, smoking, and even consuming an unnamed plant that Héloïse purchases from a woman who promises that, under its spell, time will slow down—the dream of all who are newly in love.

Meanwhile, Marianne must complete the portrait, but this time it’s a collaborative project between the two women, with Héloïse posing at length and drawing out Marianne during sessions. Marianne, who learned portraiture from her father, tells Héloïse about the difficulties of making her way in a male-dominated field. She’s not allowed to attend life-drawing sessions with unclothed male models, supposedly for reasons of modesty, but Marianne suspects that the real reason is to prevent women from learning how to draw men, so that they cannot depict important subjects like war and mythic heroes. Héloïse questions this definition of importance, and in one pivotal scene, she encourages Marianne to paint the subjects that only women have access to.

Because their time together is so limited, the women are quickly forced to reflect upon how they will remember each other after they are inevitably broken apart. As Marianne’s departure nears, it’s poignant to realize that the intense looks she gave Héloïse early on, in order to complete her portraiture assignment, will serve a second purpose: to look back on an intense, too-short love affair. This is not an age of FaceTime or even photographs, and all that will tangibly survive the affair is Marianne’s artwork. Yet, a delicate epilogue, which reveals Marianne’s and Héloïse’s divergent futures, suggests that many of the images we’ve seen in the film itself are memories that Marianne carries with her.

Hannah Gersen is a fiction writer and staff writer at The Millions. Her debut novel, Home Field, was released in 2016. She writes about movies on a semi-regular basis on her blog, Thelma and Alice.