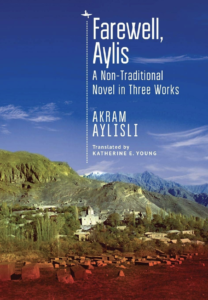

Book by AKRAM AYLISLI

Translated from Russian by KATHERINE E. YOUNG

Review by OLGA ZILBERBOURG

Contemporary books emerging from post-Soviet countries often deal with the dehumanizing effect of the region’s systems of government on its victims, seeking to trace and partially redeem the psychological and physical harm many have suffered. For understandable reasons, few authors care to look at the perpetrators, at the people who committed murders and mass murders, informed on and denounced their neighbors. Yet, in the post-Soviet reality, often it’s these people and their descendants who have risen to the top, taken charge of the new nation states, and written their laws.

It is in this context that Akram Aylisli, in post-Soviet Azerbaijan, gathers together the three novellas and closing essay that comprise his “non-traditional novel,” Farewell, Aylis. Born in 1937, Aylisli achieved fame in the Soviet Union for his earlier trilogy People and Trees. Though pieces of this new, remarkable book have appeared in Russia, the collected Farewell, Aylis, published as a result of the efforts of his American translator, Katherine E. Young, does not yet exist in any other language. Aylisli completed the first novella in 1991 and the final essay in 2016. Working from Russian translations of the original Azeri (two by the author himself), Young has given great attention to Aylisli’s unique style that combines elements of socialist realism, Middle Eastern and Persian tales, and social satire. Each piece is set in a different time and place and is populated by different protagonists, yet a continuity exists across the whole. What unites these four works is their engagement with historic trauma and the way hushed-up violence and wrongdoing are transmitted through generations, destroying not only individual lives but also the character of the village, region, and country that guilty people inhabit.

To simply survive in the Soviet Union, people were compelled to commit acts that they found morally questionable, from joining the Komsomol—the Communist Youth organization—and bearing flags on parade days to voting “yes” or abstaining from perfunctory elections. But to rise to positions of power within the Communist Party ranks, people often needed to perform larger transgressions: denounce their coworkers, spy on their neighbors. By the time the Soviet Union dissolved and tumbled into capitalism, most of its citizens (save a handful of dissidents) were complicit in a system that had helped normalize bad behavior in society. In the late 1980s, Aylisli himself briefly served as a Secretary of the Writers Union of Azerbaijan and was an honoree of state prizes. He witnessed first-hand the way progressive socialist ideology proved itself unequal to the hunger for power and material possessions, for large apartments and imported cars.

Aylisli opens Farewell, Aylis in the Soviet era, with the novella “Yemen.” Safaly muallim (a respectable way of addressing a teacher), the director of a literary institute in Azerbaijan’s capital city of Baku, accompanies Ali Ziya, “the great writer, great scholar, and great public figure” (a Party functionary), on a trip of cultural exchange. The two travel to Yemen, where Ali Ziya falsely accuses Safaly of harboring a wish to run away and hide in the American embassy, an accusation that results in Safaly’s forced resignation and becomes the foundation of Ali Ziya’s rise to greater political power. Perhaps, in his own path to the directorship of his institute, Safaly had not been entirely above reproach—Aylisli tells us, for example, that the trip to Yemen came about because Ali Ziya had hoped for an exchange of favors: “it was Ali Ziya’s goal to set up [his daughter] at the institute where Safaly muallim was rector. And if Ali Ziya hadn’t had that goal, Safaly muallim would never have seen Yemen.” Whatever they may have been, Safaly’s transgressions are comparatively minor, and when Ali Ziya pushes him aside, he chooses not to fight but to step away from his post.

The fallen Safaly then comes to be tormented by his nephew, Tariel, who has risen to a position of significance in Moscow and returns to Baku, vying for Safaly’s centrally located apartment and angling to dispossess his uncle. Using the rising wave of violence against Armenians, Tariel scares Safaly’s next-door neighbor, an Armenian woman, into selling her apartment to him and moving to Moscow to live with her sister. Tariel schemes to unite the two apartments into a single large one by tearing down the wall that separates them. So terrified is Safaly of losing his independence that he tries to exchange his apartment for a smaller, more undesirable one—in a vague hope of getting his nephew off his back. The attempt is unsuccessful and the novella leaves Safaly roaming the streets of Baku, afraid to return to his own home.

The second novella, “Stone Dreams,” completed in 2007, picks up the narrative where “Yemen” leaves off—with an elderly man, roaming the streets of Baku, afraid to go home. This is a different old man, Nuvarish Karabakhly, an actor, instead of a literary scholar, but the situation is similar: a minor Party functionary has seized the apartment of Nuvarish’s Armenian neighbor, Greta Sarkisovna, and turned it into a brothel. This is the winter of 1990; Gorbachev’s reforms were followed by ethnic violence between Azeris and Armenians; Baku is crowded with “yerazis”: ethnic Azeris who had been displaced from their homes in Armenia. Armenians who live in Baku are quickly becoming targets of violence. Greta Sarkisovna died by falling off a balcony, and Nuvarish believes that the Party functionary murdered his neighbor because he wanted her nice apartment. Nuvarish is terrified: “one fine day [the Party functionary] could easily take Nuvarish himself and throw him off a balcony and call it suicide.”

Nuvarish isn’t Armenian, and as an old man, having lived through the Soviet Union, he attempts to navigate his reality without expressing a strong opinion about whose side of the conflict he’s on. However, as the violence between Azeris and Armenians escalates, it becomes impossible to preserve neutrality. Nuvarish witnesses a group of “yerazi” throwing an old Armenian into a frozen pool and kicking him to his death, and when another actor, Sadai Sadygly, also Azeri, steps in and tries to defend the dying Armenian, the crowd attacks him. Nuvarish brings the badly beaten Sadai Sadygly to the hospital.

In the scope of the book as a whole, the actor Sadai Sadygly is endowed with the strongest moral authority. He is the only one who’s had the backbone to resist favors from the Party leadership, going so far as to refuse a personal apartment. What makes him different from his peers? Perhaps, he refuses to conform because “[h]e’s a born Don Quixote,” as a physician treating his unconscious body suggests. Perhaps, he processes historical trauma differently from his peers: “He simply can’t forget the slaughter the Turks conducted [on Armenians] in [his ancestral village] Aylis,” his wife Azada suggests. Perhaps, it’s the quality of love that he’s capable of: “From birth he was an honest, conscientious, and vulnerable person. […] He loves his people—that’s what distinguishes him from the ill-assorted, brainless screamers who’ve now multiplied around the world like mushrooms after rain,” says his father-in-law. “His character is entirely child-like,” Nuvarish explains. “When he was still little, out there in the village someone shot a fox cub in front of him. So, he remembers that cub to this day. He’s told me about it many times. And every time he has tears in his eyes, that’s the kind of person he is!” There is no final consensus, only a choir of people whom Sadygly loved and who loved him.

If there ever had been a time in history when truthtellers were rewarded, Farewell, Aylis makes clear, the Soviet era was not that time. As the Soviet Union was falling apart, people like Sadai Sadygly who held on to their morals became the enemy of those with power. Having grasped this in his attempts to stand up for the Armenian, Sadai Sadygly refuses to wake up (we get to witness the thought process of this dying man). As we are told that Sadai Sadygly has died, we learn that Nuvarish Karabakhly, too, is dead—“They say he threw himself off a balcony.”

So, what becomes of a country, newly independent and led by denunciators and murderers and their descendants? In the third novella, Aylisli imagines a fictitious post-Soviet country he calls Allahabad and prefaces the text with this disclaimer: “This work is not about SOMEONE but about SOMETHING. To be precise, about gluttonous regimes that devour themselves.”

Completed in 2010, “A Fantastical Traffic Jam,” opens with another elderly gentleman. His name is Elbey, and he, too, finds himself homeless and locked out of his office. Just that morning, he was the right-hand man of Allahabad’s Rais (in Azeri, “a leader”)—a dictator. As a child, Elbey had witnessed the Rais’s love affair with Elbey’s mother and had kept the secret to himself. As the Rais advanced in the Party ranks and solidified his power, he valued Elbey’s ability to keep his secret and Elbey became his eyes and ears, going to tearooms about town and gathering the rumors people were spreading about the Rais. Elbey is now married to the Rais’s niece; they have two sons who live abroad, and a daughter, Guinel, who stayed in Baku and is raising her three children.

The family connections, however, prove to be insufficient when Elbey fails to inform the Rais of a new nickname, invented for him by an art teacher of his youngest grandson. Elbey’s duty is to put the young artist behind bars, but his daughter, Guinel, comes to the teacher’s defense, and he allows her words to sway his judgement. The moment of pity for the young man—the moment when Elbey shows himself capable of that emotion—has the weight of a punishable offense in the eyes of the Rais. When he understands his mistake, Elbey accepts his punishment and only wonders what kind of death sentence he will receive. “The Master was always able and loved to manipulate the emotions of people in order to bring everyone to full obedience,” Elbey thinks. “Even in those situations where he sentenced people simply to an inglorious death without resorting to crude violence.”

Elbey is exiled to his dacha in the countryside, which he finds ransacked, his housekeeper, missing, and his dog, gruesomely dead. Near the refrigerator, there are two cases of Russian vodka. “It occurred to [Elbey] that one of the simplest methods the [Rais] used to eliminate people was to gradually instill a passion for drinking in the undesirable person and get rid of him that way. In fact, those cunning and deeply confidential tasks had even been handled by Elbey.” It takes Elbey three days to drink himself to death.

The trilogy concludes with death and hopelessness; “Farewell, Aylis,” the essay that follows is, if possible, even darker. The author, who had as a young man adopted the name of his ancestral village as his pen-name, Aylisli, recounts receiving the news of the murder of the last Armenian woman in Aylis in the middle of the night of January 13, 1990. “The sincere, good, pure-as-the-driven-snow Tamara Atabekyan—the last Armenian in Aylis, who didn’t even know Armenian.” In this essay, we come to understand that grief over this murder inspired the author to go against the political fervor of his fellow countrymen and to write about the long hushed-up persecution of the Armenian population, to speak out about Azerbaijan’s role in the Armenian genocide.

Following the publication of “Stone Dreams” in a Russian magazine, and likely as a result of a direct command of Azerbaijani leadership, Aylisli tells us, his fellow villagers, each of whom he knew personally, staged and videotaped a bonfire of his books. Aylis was no longer his, he laments in the essay, and would never be his again. But the morning after watching the video of the book burning, he was rejoicing. “The Aylis taken away from me that day by the potent hand of the authorities hadn’t been my Aylis for a long time already. It was their Aylis: without God and without Memory, without History, and without a Biography.”

A writer, Aylisli teaches us, has no allegiances to a country, an ethnicity, a religion, not even to his own birthplace. “But he’s always responsible for the moral appearance of his own people, for the spiritual state of his own fellow citizens.” And this writer has found the spiritual state of his fellow citizens to be in a dire condition.

Aylisli, insisting on his role as a truthteller, finds himself increasingly at odds with his countrymen and no longer willing to stay silent. His main addressee with this book is his country’s Rais—in the final essay, he addresses Azerbaijan’s president directly and calls him by his name, Ilham Aliev. He imagines himself in a conversation with Aliev, wishes to show him Aylis the way it used to be. But even in his imagination he’s unable to get Mr. President to respond. As Farewell, Aylis concludes, it leaves a reader with a sense that an individual voice trying to resist the culture of violence is powerless against the status quo; nonetheless, Aylisli’s voice feels necessary and urgent.

Olga Zilberbourg’s English-language debut, Like Water and Other Stories, is forthcoming in September 2019 from WTAW Press. Her fiction has appeared in Alaska Quarterly Review, Scoundrel Time, Confrontation, Narrative Magazine, Epiphany, Santa Monica Review, J Journal, and elsewhere. She co-hosts the weekly San Francisco Writers Workshop.