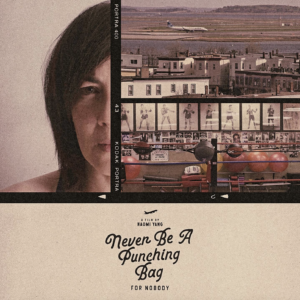

Film by NAOMI YANG

Review by HANNAH GERSEN

Sometimes visiting a new neighborhood can change your life. While scouting locations for a fashion shoot, filmmaker Naomi Yang happened upon a boxing gym in East Boston. The modest second-generation family business, with its sparring ring and wall of framed black-and-white photographs depicting local boxers, seemed like a great backdrop. Unfortunately, the gym’s owner and head coach, Sal Bartolo, Jr., disagreed, citing aprevious photo shoot that had gone badly, with high heels destroying his mats. There would be no fashion shoots in his gym. Instead, he gave Yang his pitch to all visitors, telling her to come back for a free boxing lesson. In voiceover, Yang confides to us that she did not take the offer seriously and didn’t plan to return. And yet, a few weeks later, she did. Part of her was holding out hope that Bartolo would change his mind. But another part felt drawn to boxing, and Bartolo’s gym would soon become the center of her life. Yang’s documentary tells the story of how this chance meeting at a boxing gym brought her into a deeper understanding of herself, and of the ways bullying forces can leave their mark on places as well as people.

The first half of Yang’s documentary is devoted to Bartolo, whose love of boxing seems to infect all of his students, Yang included. Bartolo is a small, wiry, seemingly ageless man with a shaved head, lively eyes, and friendly demeanor. His energy level is high, even when he’s sitting in his cluttered back office, showing Yang video clips from boxing matches. As a coach, he’s calm and direct. He doesn’t raise his voice or mince words. The phrase “never be a punching bag for nobody,” comes from Bartolo, his version of “a good defense is the best offense.” He takes on students of all ages and skill levels, and his gym is as welcoming to women as it is to men. Yang quickly finds community among the other students and signs up for weekly classes, then biweekly practices. Before she knows it, she’s going to Bartolo’s Boxing Club five days a week.

Going to Bartolo’s means spending more time in and around East Boston, and the heart of this short but substantial film is in Yang’s exploration of the neighborhood that surrounds her adopted gym. Even before her boxing habit took hold, Yang tells us, she had an abiding interest in the edges of urban areas, the zones where cities meet their geographical limits and domestic life is interrupted by industrial infrastructure—or nature. She finds both these elements in Winthrop and East Boston, where peaceful backyard views of Boston’s last remaining salt marsh are marred by low-flying planes coming from or going to Logan Airport—sometimes as many as 120 take-offs and landings an hour. Yang finds beauty in this juxtaposition, allowing the camera to linger on marshland surrounding the airport, tidal flats, and peachy sunset views unobstructed by tall buildings. It seems peaceful and far from the bustle of urban life—until the planes fly overhead, so low they seem to have gone off course.

As Yang explores the area, she learns more about the devastating impacts of Logan’s expansion into East Boston. She finds residents eager to share their stories, striking up conversations when they see her out filming. Many, like Bartolo, have been living there for several generations. In the early years of Logan, the airport was the pride of the neighborhood, a place to watch small airplanes take off and land. Runways were shorter, and farther from residential areas. But things changed in 1959, with the advent of jet engines, which were two times louder than piston engines and required longer runways. With the expansion of the runways, the airport was suddenly a lot closer. One resident tells Yang that his rooftop antennae were routinely knocked over by low-flying planes. Another is certain that his deafness in one ear is due to the sound of the planes flying overhead—as a side sleeper, one ear was always protected by the pillow, but the other was subjected to the sound of jet planes coming in for a landing, all night long.

As air travel grew, so did Logan Airport, taking more bites out of the surrounding neighborhoods. It swallowed up Wood Island Park, a vast recreation area designed by Frederick Law Olmstead. The houses and trees surrounding the park were also removed, using eminent domain, with the government offering residents the option to sell their homes at market value or to lift their houses off their foundations and relocate them to another lot in the neighborhood. Many residents chose the latter, a process captured in news footage of oversized trucks bearing three-story houses past rows of onlookers. Yang intersperses archival video with still photographs, maps, and her own present-day footage. The loss of Wood Island Park—which still has a T stop bearing its name—struck me as particularly devastating: 70 acres of rolling hills, playing fields, trees, and waterfront vistas—a shared community space for playing, picnicking, relaxing, and celebrating—was razed and leveled in one weekend. In its place is a long, flat, fenced-off runway. Yang’s voiceover does not ask if the benefits of Logan’s expansion were worth the damage to the natural environment and human community; those questions naturally arise. It’s clear, though, that the business travelers who rely on the convenience of international flight often live far from airports, and bear none of the direct costs of airport expansion. With the planet overheating, I also couldn’t help thinking of the increased carbon emissions that came with the advent of all those deafening jet engines.

In the late 1960s, inspired by the Civil Rights movement, a group of local women took to the streets to fight back against Logan’s encroachments. They blocked incoming dump trucks barreling down their main thoroughfare, Maverick Avenue, carrying materials to build new runways. The trucks brought an extra layer of noise and dust, on top of the daily roar of the aircraft overhead. The women, who later became known as the “Maverick Mothers,” stood in the middle of the avenue with their baby carriages and strollers—their way of letting the city know that the trucks needed to find a new route. Their protests were met with rough treatment from the police, captured on film and reported by the local news media. It didn’t look good, and the trucks were re-routed. That was the beginning of many years of protests from local mothers, who fought for protection against noise pollution and other environmental contaminants.

Yang finds a common thread between the Maverick Mothers and Bartolo, weaving together stories of kitchen-table organizing with the exploits of local boxers to reveal the community’s fighting spirit. To this she adds her own reflections on boxing, a sport which ultimately helped her confront her own passivity, a defense mechanism she had never fully acknowledged before working with Bartolo. In an essayistic voiceover, Yang describes how, when she first tried to spar, she found herself giggling in discomfort and unable to hit another person. Over time, she realized that her inability to show aggression was a coping strategy from childhood, a way of dealing with her parents’ angry mood swings. Yang delves into the therapeutic aspect of boxing with a certain restraint. She shares a few snapshots from her childhood, and there are a few passages that show her working out and sparring, but usually she’s behind the camera, keeping it trained on the people and places that brought her to this new understanding. This choice is surprisingly expressive, and it’s enhanced by the soundtrack, which Yang wrote and performed herself.

Some viewers may recognize Yang from her career as a musician—though I personally didn’t make that connection until later. She was a member of Galaxie 500 and Magic Hour and currently tours with Damon & Naomi, a psychedelic folk duo. Yang also directs music videos and works as a graphic designer. She’s an artist in a variety of mediums, yet aside from the fashion shoot that brings her to Bartolo’s gym, Yang makes little mention of her professional life and more public-facing roles; instead, we get to know her through the images she collects with her camera and shares with us. Her love of nature is evident in her photographic compositions that frame the wild spaces between and behind buildings. She’s also alive to hidden human histories, showing the remnants of the past tucked away in parks, history books, houses—and of course, in ordinary people, who sometimes just need to be asked to share their stories. There’s a lack of vanity and an open-ended curiosity to Yang’s filmmaking that reminds me of Agnes Varda’s later documentaries shot with hand-held cameras (The Gleaners & I; Faces, Places). By the end, you feel that you’ve witnessed an intimate excavation of a person and a place.

Hannah Gersen is the author of Home Field. Her second novel We Were Pretending is forthcoming from Little A in 2024. In her monthly newsletter, Thelma & Alice, she recommends movies written and directed by women: https://thelmaandalice.substack.com