I know you think that evil always fades

like grass, that even when it spreads itself

like a bay tree, or cobwebs on a shelf,

time will turn it back, as sun with shade,

All posts tagged: Nathaniel Perry

What We’re Reading: April 2025

Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

The long New England winter is finally thawing, and here at The Common, we’re gearing up to launch our newest print issue! Issue 29 is full of poetry and prose by both familiar and new TC contributors, and a colorful, multimedia portfolio from Amman, Jordan. To tide you over, Issue 29 contributors DAVID LEHMAN and NATHANIEL PERRY share some of their recent inspirations, and ABBIE KIEFER recommends a poetry collection full of the spirit of spring.

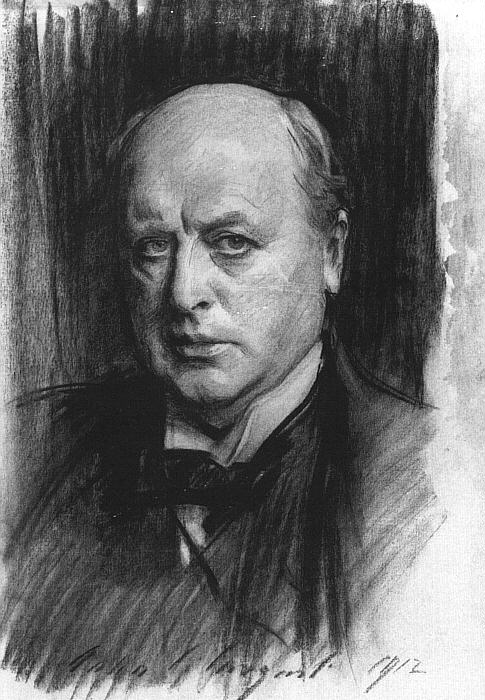

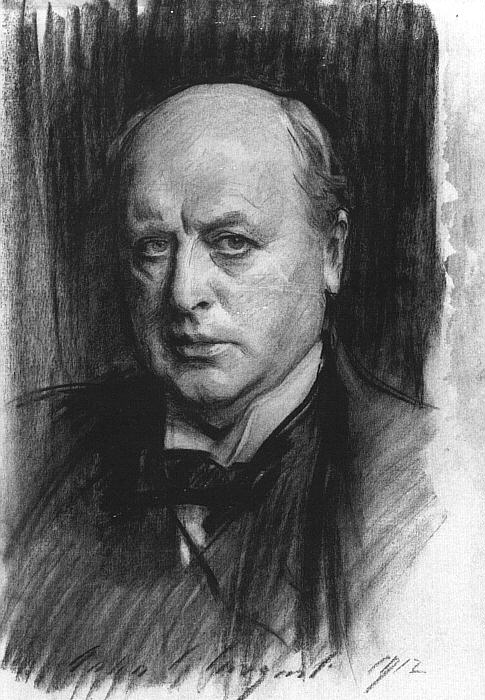

Henry James’ short works; recommended by Issue 29 contributor David Lehman

I’ve been reading or rereading Henry James’s stories about writers and artists: “The Real Thing,” “The Lesson the Master,” “The Death of the Lion,” “The Tree of Knowledge,” “The Figure in the Carpet,” “The Aspern Papers,” et al. His sentences are labyrinthine, and you soon realize how little happens in a story; the ratio of verbiage to action is as high as the price-earnings ratio of a high-flying semiconductor firm. Yet we keep reading, not only for the syntactical journey but for the author’s subtle understanding of the artist’s psyche—and the thousand natural and artificial shocks that flesh and brain are heir to.

The Most-Read Pieces of 2024

Before we close out another busy year of publishing, we wanted to take a moment to reflect on the unique, resonant, and transporting pieces that made 2024 memorable. The Common published over 175 stories, essays, poems, interviews, and features online and in print in 2024. Below, you can browse a list of the ten most-read pieces of 2024 to get a taste of what left an impact on readers.

*

January 2024 Poetry Feature: Part I, with work by Adrienne Su, Eleanor Stanford, Kwame Opoku-Duku, and William Fargason

“I wrote this poem on Holy Saturday, which historically is the day after Jesus was crucified, and the day before he was resurrected. That Spring, I was barely out of a nervous breakdown in which I had intense suicidal ideation … The moments of quiet during a time like that take on more meaning somehow, reminders I was still alive. And that day, that Saturday, I saw a bee.”

—William Fargason on “Holy Saturday”

October 2024 Poetry Feature: New Poems By Our Contributors

New Poems by Our Contributors NATHANIEL PERRY and TYLER KLINE.

Table of Contents:

-

- Nathaniel Perry, “34 (Song, with Young Lions)” and “36 (Song, with Contranym)”

- Tyler Kline, “Romance Study” and “What if I told you”

34 (Song, with Young Lions)

By Nathaniel Perry

All the young lions do lack

bones. They lie wasted on grass,

cashed out, exhausted and un-

delivered. A poor man cries

eventually. A troubled

friend cries eventually.

May 2020 Poetry Feature

By PETER LaBERGE, ROSE McLARNEY, NATHANIEL PERRY, and KERRY JAMES EVANS

New poems by our contributors:

Peter LaBerge | Reliquary (June)

Rose McLarney | Her Own

Nathaniel Perry | March (I’m far away from home today)

Kerry James Evans | Golgotha

Reliquary (June)

By Peter LaBerge

midnight & the dead boys introduce

themselves once more, not by name

but by what they’ve left behind—

hello Unlicked Stamps.

hello Blanched Almond

Moon.

hello Board Games in the

Pantry.

another queer boy’s death in media

res—

the unblinking eye

of a cavalry horse gone

belligerent…

last monday it was the

moon.

nobody asked the moon if it

was

finished being the moon

before god popped it from

its socket.

more queer boys in media res. the

queer boys, first their names left out

of the news—

hello John Doe.

hello John Doe.

hello John Doe.

on TV, they sprout names. on TV,

we watch each as boys, falling

through the snow of grainy home

videos—

i fear we’ve etched each

little face

in smooth clay like memory,

one next to the other,

then printed them with

ground charcoal

then left them out in the late-

spring rain

to de-face like history—

Her Own

By Rose McClarney

Sillage is the scent following after

the wearer of perfume moving through a room.

It comes from the French for a wake,

as in the trail left by a jet through the sky.

Once, she thought it was chopped corn stalks,

fermented and fed, in the winter, to pigs.

You can guess the kind of place she came from,

how much of anywhere she’d been. When wind

blew from the direction of the silos,

she didn’t move, would only

raise her own hand to her nose for cover,

for its soap smell, and continue whatever task

she was set to. Flight, that there was other air,

were not ideas she held then.

March

By Nathaniel Perry

I’m far away from home today

and everything is breaking.

The heat pump stopped, the well went out,

and the dog is still making

us worry with what she is and isn’t

doing. Kate’s been calling

me asking for help, and I

am, to be honest, failing

to be much help at all. I sent

a friend to fix the well,

which he did, but that is really the only

thing I managed. If a bell

rings and you’re not there to hear it

or attend to what it means,

what is your relationship

to the bell? I’ve never been

a monk, but if you don’t rise and pray,

the prayer goes on without you,

I know. When Merton asked his abbot

if he could travel, he flew

to Thailand and died, or maybe was killed,

but his prayers went on without him

either way: he left his things at home

and knew no more about them.

It is so easy to separate,

I forget the work of staying

whole, is maybe another way

of putting it, of paying

my respects to what I’ll leave behind.

Today, I’m going home,

but Merton never made it back,

to M, to the small stone

hermitage he’d barely lived in,

to his east-facing Jesus

or to the knobby hills that rise

like beautiful excuses

around Gethsemani. And it’s useful

to remember that that will be,

one day, my fate as well. My kids

will stand at the spring and see

a sunset I won’t see. The beech

and hickory will clack

indifferent branches above the field

beside them as they walk back

to the house without me, gravel thin,

not one stone on a stone,

the sky above them blue but weird,

bare and blank as bone.

Golgotha

By Kerry James Evans

I feel better about my peanut butter

and jelly sandwich, the pears

swelling behind the house,

where a chubby train appears each day

at 3:00pm, its diesel engines

rattling so loud, they scare squash

clear off the vine. Don’t worry.

Redemption lurks in the back pew

of a rural Baptist church—

or that’s what we tell ourselves

after raising our heads for the altar call

to watch Jethro Smith finally

get saved. Everyone’s so proud

of Jethro for seeing the light,

which he will truly see next Tuesday,

when he rolls his Ford F-150 over a guardrail

and into the Buttahatchee River,

where so many dead bodies

have been devoured, even the river

has lost count, cattle-thick

water churning like the preacher’s doubt

when he commits the unfound body

to the earth. He got right with God,

he’ll say, Bible in right hand,

shovel in left. He’ll fling dirt

onto an empty coffin, then walk away,

head slumped like a yoked mule—

like the rest of us bent under

the weight of our collective

disappointment. But how can I talk

about the future when the past,

virulent as the holy ghost, knocks

like an old friend peddling

fire extinguishers—who, like a

translucent Gecko, shimmies

through the door with a big red can

of what the hell happened?—

and my God, how do I get him

out of my house? What I wouldn’t give

to pursue other conversation—

one about how proud I am

for all your success, or Damn

if these aren’t the sweetest pears,

and Can you believe we’ve been

getting so much of this good rain!

I know it’s foolish, but I listen

in those flickers between breaths

—when a dialect gives way to a presence

beyond reason, a place so holy

it can hardly be seen or heard

—like dew drops on a watermelon.

Call it Golgotha. The crown of a hillside

made quiet by a simple breeze, a song

of such exacting glory you leave

the body altogether, and, like Jethro,

are content to drift downriver.

Kerry James Evans is the author of Bangalore (Copper Canyon). He is the recipient of a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship and a Walter E. Dakin Fellowship from Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and his poems have appeared in Agni, New England Review, Ploughshares, and other journals. He will join the MFA in Creative Writing faculty at Georgia College & State University this fall.

Peter LaBerge is the author of the chapbooks Makeshift Cathedral (YesYes Books) and Hook (Sibling Rivalry Press). His work received a 2020 Pushcart Prize for Poetry and has appeared in AGNI, Best New Poets, Crazyhorse, Kenyon Review Online, Pleiades, and Tin House, among others. Peter is the founder and editor-in-chief of The Adroit Journal, as well as an incoming MFA candidate and Writers in the Public Schools Fellow at New York University. For more, visit peterlaberge.com.

Rose McLarney’s collections of poems are Forage and Its Day Being Gone, both from Penguin Poets, as well as The Always Broken Plates of Mountains, published by Four Way Books. She is co-editor of A Literary Field Guide to Southern Appalachia, from University of Georgia Press, and the journal Southern Humanities Review. Rose has been awarded fellowships by the MacDowell Colony, and Bread Loaf and Sewanee Writers’ Conferences; served as Dartmouth Poet in Residence at the Frost Place; and is winner of the National Poetry Series, the Chaffin Award for Achievement in Appalachian Writing, and the Fellowship of Southern Writers’ New Writing Award for Poetry, among other prizes. Her work has appeared in publications including The Kenyon Review, The Southern Review, New England Review, Prairie Schooner, Missouri Review, and The Oxford American. Rose earned her MFA from Warren Wilson’s MFA Program for Writers. Currently, she is Associate Professor of Creative Writing at Auburn University.

Nathaniel Perry is the author of Nine Acres (Copper Canyon/APR, 2011). Recent poems and essays appear in Kenyon Review, Image, Fourth Genre, and elsewhere. He is the editor of Hampden-Sydney Poetry Review and lives in rural Virginia.

On Ice

The dogwood makes a second

skin of winter rain.

The form’s the thing, the sky

is saying as it drains

our language of descriptors:

crystalline?

May 2015

Please enjoy five new poems by our contributors.

Function of Water

By NATHANIEL PERRY

On rainy days the place seems smaller,

acres still ringed and shrouded by trees,

but the sky is closer, like something landing.

I know you’d like to ask me—please