Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

To kick off the autumn column, our contributors bring you three novels that invite unexpected encounters with time. A recommendation from former TC submissions reader SAMUEL JENSEN trains our sights on the future of the American dream; with LILY LUCAS HODGES, we unearth an artifact of historical erasure; and with HILDEGARD HANSEN, we finally transcend history through prose that gropes at the primordial core of life.

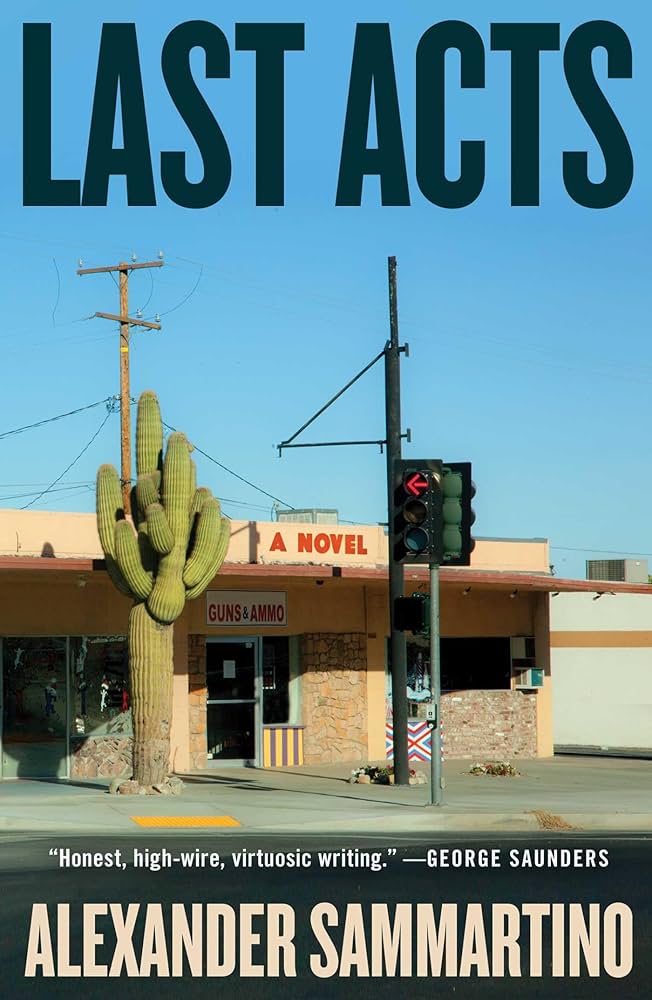

Alexander Sammartino’s Last Acts; recommended by Reader-Emeritus Samuel Jensen.

I picked up Alexander Sammartino’s debut novel, Last Acts, because of the cover. Seeing it at the book store, it was as if someone had walked up the road from my childhood home, aimed their camera across the arroyo, and snapped a picture. I’m from El Paso, Texas and Sammartino’s novel is set in Phoenix, Arizona—two very different places—but still: a sunbleached strip mall with a gun shop in it, burning under a merciless blue sky? It was like running into someone you’re not sure you wanted to see again.