By RICHARD GWYN

Leaving behind the clamor of Mexico City, I catch a bus and cross the wide altiplano. Behind the tinted windows are strewn the blackened remains of trees and cactus, upon which perch large, dark birds. Half asleep on the silent bus, which plows like an ocean liner across the prairie, I think about the birds outside, peering into passing vehicles from their watch-posts. I fall asleep and dream that the birds standing aloft the cacti are truly enormous, and that they have a name that no one can pronounce. Even the local people are confused because they cannot utter, or even remember, the names of these birds, which means, in their language, “those whose croak inspires terror.” It is not known, the people in my dream tell me, whence the name originated, nor have any of the birds been heard to croak; they all remain implacably silent. If one of the birds were to call out, it would signal the end of the current universe, the death of the sun, and the whole terrible process of regeneration would begin once more, following the previous cycles of destruction by (i) tigers, (ii) the winds, (iii) rains of fire, and (iv) water. The inhabitants of the plain, when they die, are roasted in a clay pit and eaten by their relatives and friends. Their livers and other inner organs are eaten by their closest kin. Their feet are cut off and left out for the birds whose name no one can remember, as it is believed that this will prevent them from making their dreadful sounds. Mictlantecuhtli, Lord of the Dead is in there somewhere, hovering in the debris of my dream.

When I am fully awake, or at least in a state resembling wakefulness, I wonder: did I actually see those birds, or did I hallucinate them? It is so hard to distinguish at times between the things we see and the things we remember and the things we think we remember and the things we never saw but read about, and the things we wish we had seen and so retrospectively invent, and the things we will never see but have experienced vicariously in a story told by someone else, a friend or stranger. And then a mist falls upon the plain and the next time I look there is a forest, barely visible through the thick cloak of fog, and the windows of the bus have steamed up with the change in temperature. But the birds, I know, are gone.

We arrive at Xalapa in heavy rain, I hail a taxi from the bus station and find that the route across town is cordoned off for a Mayday demonstration. The taxi driver curses impressively, finds a way around, and drops me off at my hotel, a modest establishment with rooms at ground floor level that overlook an inner courtyard.

I am hungry and set out up the street, turn into Callejón Diamante, and enter La Sopa canteen. An older man with a white moustache, white shirt and white cowboy hat is playing the harp. I clock the harpist clocking me, which gives me pause for thought: why do some people act as if they recognize you, when they could not possibly recognize you? Or is the pretense of recognition a ploy they use in order to get into conversation later? Has this guy mistaken me for someone else? Do I have a double? My mind is adrift with the kind of chaotic speculation that often comes over me when I am in a new place, and on other random occasions.

I head towards the rear of the cantina, sit at a corner table, my back to the wall, and order: chickpea soup, pork in salsa verde with pasta, and a beer. The soup arrives, along with tortillas wrapped in a cloth. I take in my surroundings. The cantina has a pleasant, floral ambience, as though it were located in a small city park, complete with bandstand. The musicians take a break, and the cowboy harpist makes his way down to the washroom. When he passes my table he nods and says, “Buenas tardes,” in familiar fashion, confirming my sense of mistaken identity. But this is not so strange, I reflect; a friendly old fellow in a Stetson who plays the harp, saying hello. He reminds me of the wise cowboy in The Big Lebowski, played by the actor Sam Elliot. I finish the chickpea soup and await the arrival of the main course. The harpist comes out of the men’s room, stops by my table, greets me again, and then says, in Spanish: “Around here they call me The Ambassador,” and reaches out his hand for shaking.

Now this I do find odd; first, as his introduction suggests that the cowboy does not in fact know me, and that either I was mistaken in forming the impression that he thought he did, or indeed, that he mistook me for someone I was not; and secondly — and more significantly — I was under the impression that I was the ambassador, or at the very least a variation on the theme, having been appointed “Creative Ambassador” by the Arts Council of Wales for the year, and entrusted in this capacity to forge links with the literary communities of several Latin American countries. I am about to say something to this effect, and then realize I have been spending too long inside my own head: this happens when one is travelling alone. One begins to make assumptions that other people are privy to what one might be thinking, and this is absurd. I do not have a monopoly on the role of ambassador. I am not even a proper ambassador. Perhaps “The Ambassador” is the harpist’s stage name. Or perhaps, I reflect, he is a retired drug baron nicknamed “The Ambassador” for his talent in negotiating his associates’ passage to the afterlife, and who has since mended his ways and taken up playing the harp in a Xalapa cantina, where no one knows of his sinister past and his reputation for dealing out summary justice. Nonsense, I reply to myself, there is no such thing as a retired drug baron, only dead ones; in fact there are no such things as “drug barons,” just narco bosses. He is simply a nice old man who plays the harp. I stand, to be polite, shake the man’s hand with firm sincerity, and smile back at him.

“Mucho gusto,” I say. He seems on the verge of saying something in return, his gaze lingering on me, but changes his mind, perhaps realizing that I am not someone he especially needs to know, and moves on, back to his harp.

When I leave the cantina it is still raining. On the way, several pick-up trucks pass by, carrying soldiers dressed in black waterproofs. I go to my room and read a short story by Juan Rulfo, have an early night.

The next morning, immediately after breakfast, I set off for the museum of anthropology, a half hour’s walk under light but persistent drizzle. It is still early, and the place is almost empty. Beautifully laid out, the museum is spacious, bright, and populated with large and imposing stone carvings from the Olmec era (2,500 – 500 BCE). I am struck by the simplicity and solidity of these forms which strike me as carrying an intangible, spiritual quality that is, however, quite beyond my ability to decipher. I find them deeply moving, but realize that I cannot possibly “see” these works for what they are, in the spirit in which they were created, and that this, rather than being frustrating, provokes a feeling of wonder at their richness of expression in and of itself, and I am left without comprehension, as though understanding were itself irrelevant, and the beauty of these implacable, somber faces lay precisely in their inaccessibility, their removal from all interpretation. One smaller piece, in particular, engages my attention.

In “Dualidad,” as it has been named, the face is half-covered by a dense, featureless carapace, as though the subject were in a crisis of self-disclosure, and was being violently silenced against its will. The half-face that is revealed remains impassive, unaware that this terrible erasure is being visited on it. It speaks to a duality which I feel very keenly at present, a striving to rid oneself of another, past identity. It unsettles me in the way that only an uncannily familiar object can, as though reminding one of something or someone one is trying to forget, and to which, however, one is permanently conjoined. I am entranced.

I spend a couple of hours wandering through the halls, becoming saturated with Olmec images of human figures, including several which depict men, or androgynous beings, alongside their totem animals, and a smaller array of jaguars and serpents.

On leaving the museum, I decide, on a whim, to visit a neighboring town, Coatepec (the accent is on at): it fulfils at least one of the criteria I employ when deciding whether or not to visit a place: I like its sound, which carries the resonance of something at once remote and reassuring. I flag down a taxi driven by a man with stupendously fleshy earlobes, earlobes that remind me of small whoopee cushions or rolled dough or molded plasticine, which leads me to speculate whether the ears continue to grow throughout a person’s lifetime, as I read somewhere. Once we get going, and he decides I am a harmless foreigner, the taxi driver chats openly about corruption in Mexican politics. He tells me things are getting worse, that the governor is corrupt, that the police are corrupt, that everything in the State of Veracruz, as he puts it, has gone to shit. We drive out of Xalapa in the rain. The traffic moves very slowly. It has been raining all morning and all last night, and throughout the previous evening, and as far as I know it has never not been raining in Xalapa.

Just outside town there is a roadblock. The young policeman, barely out of his teens, fluff on his upper lip, carries an automatic rifle and wears black body armor, leg armor, the works. He inspects the taxi driver’s ID and looks at me intensely for several seconds as though the act of staring could itself squeeze from me a confession of guilt. I am unsure whether the best response to this is to look back at him or cast my eyes down in submission to the interrogatory gaze, so end up doing both. He looks at me for an unnecessarily long time, as the rain clatters down on the roof of our car, before waving us through with an impatient gesture.

We arrive in Coataepec and immediately get stuck in another traffic jam. Nothing moves for fifteen minutes. The taxi driver asks directions of a fellow taxista whom we are stranded alongside, but the traffic doesn’t budge. I spot a restaurant, pay the taxista, and get out. It is mid-afternoon by now, and I need to eat. The restaurant has a nice inner patio with a garden area, and tables around it, out of the rain. In the garden there are roses and other flowers. The members of a large family group are finishing their meal and spend at least twenty minutes taking photos of each other in every possible combination, so that no one has not been photographed with everybody else. They have commandeered the only waiter in order to help them in this task. Every time I think they are about to leave and release the waiter—who could then come and take my order—they reconvene for a new set of photos. One of the men, a Mexican, has very little hair but a long grey ponytail, which always strikes me as a terrible style choice. One of the women—I suspect Ponytail’s sister—is married to a gringo. Perhaps they have just got married, but in a registry office rather than a church, and this is the celebratory meal. He has long hair also, but not arranged in a ponytail. He speaks Spanish well, with a norteamericano accent. I order tortilla soup and start leafing through a magazine I bought at the anthropology museum. My phone makes a noise that tells me I have received a message, which informs me, in Spanish: “Adults who sleep too little or too much in middle age are at risk of suffering memory loss, according to a recent study.” I look at the message in consternation. Too little or too much? So, you’re fucked either way. Having suffered from insomnia for much of my adult life, I am an avid consumer of any information that purports to throw light on my infirmity. Such information is almost always unhelpful. But now, it would seem, there are casualties of both too little and too much sleep. Who sends this stuff? The screen says to connect with 2225 to find out more. Then another message: “Japanese fans of Godzilla were very upset with the news trailer of this film to find that Godzilla is very big and fat: read more! 3788.” Then a link. How do you switch this crap off?

Coatepec is full of attractive buildings with courtyards. I head down to the Posada de Coatepec, a hotel in the colonial style, and go in for a coffee. A slim man in his forties with fine features, a neat little moustache, not quite a pencil moustache, and dressed in polo gear, greets me in friendly fashion, and I greet him back, once again under the impression that I have been mistaken for someone I am not. A blonde woman, also in white jodhpurs, follows the man. There must have been a polo match. How strange, I think: I have not associated polo with the Mexican upper classes. The hotel offers a nice shady patio, but we don’t need shade, we just need to be out of the rain. I sit on the terrace outside the hotel café and write in my notebook. Before long, the man who was in riding gear but has now changed into khaki slacks, pale blue shirt and black sleeveless jacket, comes and sits on the terrace also, nodding at me as though we were by now old buddies. Immediately three waiters attend to him, bowing and scraping; one of them is even rubbing his hands together in anticipatory glee at the opportunity to serve this evidently Very Important Person. The man takes off his sleeveless jacket, his gilet, rather, and immediately the second waiter scurries away, returning with what appears to be a hat stand for very short people but which is, I realise a moment later, a coat stand. Clearly the Very Important Person cannot do anything as vulgar as sling his coat over the back of a chair. Another waiter opens a can of Diet Coke at a safe distance, and only then brings it to the table, along with a glass brimming with ice. He is bent almost double, as if to ensure that no part of his body looms offensively above the person of the celebrity guest. It is one of the most extraordinary displays of deference I have ever witnessed. Then all three waiters—the one who brought the coat stand, the one with the Coke, and the one who was rubbing his hands, who appears to be a kind of maître d’—vanish inside like happily whipped dogs. Left alone, the man makes a phone call in a loud voice. He is barking instructions to some underling. He is clearly someone who is used to being obeyed, like an old school caudillo. When he has finished his call, he looks around and gets up, heading towards the restaurant, where his company—family and friends, I guess—are seated. He takes his drink with him, but within seconds one of the waiters appears out of nowhere, grabs the coat stand, and follows him in with it.

I have to go. I have arranged to meet a poet, José Luis Rivas, back in Xalapa, in order to discuss poetry matters. Rivas has translated T.S. Eliot and Derek Walcott into Spanish and is a well-known name in Mexican literary circles. I take the bus this time.

As I walk down the street from the bus station towards my hotel, a pick-up truck packed with soldiers passes by. A machine gunner is perched on the back, and he swivels the weapon to train it on me as the truck continues on its way. I am just a visitor to this town, but I have now been the subject of interest to the security forces a couple of times, and am beginning to feel a little paranoid. What would it feel like having this happen every day? How long before you cracked?

The rain has eased. I stop for a drink at a cafe and sit outside. A little girl approaches my table and tries to sell me a rose. I buy one, give her ten pesos, and tell her to try and remember not to ask me again. Barely has she disappeared when a stooped, toothless old fellow comes along, the sort of beggar who has become oblivious to rejection and insult. He stops by my table and implores in abject fashion until I relent and give him ten pesos also. I move down the street and sit outside a bar called Cubanías, and am again approached by the little rose girl, whom I remind of our agreement; she smiles coyly and backs away. I think about solitary travel, and of the hundreds of hours in which one engages in interior monologue, and the occasionally insightful moments when everything appears to make sense, or when you think you should remember something specific—the crow alighting on that tree there, the little beggar girl’s way of pushing her short hair behind her ear, the distant sound of a police siren—just in case that moment later makes sense to you, slots into a sequence of memories, and you realize why you remembered it, that it has a unique place in the order of the universe, the patterning of the ineffable, even though it doesn’t matter, none of this matters, as long as you have faith in the persistence of the murmur, and can be at ease with the perpetual babble of those background voices, of people sitting around about you, along with your own internal accomplices, whose voices come on like ambient music, and which you can tune into at will. And at times the two sources—the voices of the exterior world and the interior—join together in a stream of juxtaposed sound, and that is the persistence of the murmur…

In addition to this pervasive background murmur, memory is a constant interloper, relaying information in its haphazard way, though as I get older it is less a case of “I remember” and more as though memory were seeking me out, as if some autonomous force of memory were collaborating with my efforts, infiltrating my ability to make sense of things, rather than “I” making sense of the things I remember. In which case, does memory belong somewhere “out there” in the world—like consciousness, according to the panpsychists—and I merely tap into it? At the same time, I am all too aware that while memories are often unreliable, it is only through the act of re-constructing them that we make sense of our lives. “Life is not what one lived,” claimed Gabriel García Márquez, “but what one remembers and how one remembers it in order to recount it.”

But even that is not an entirely satisfactory explanation, as it leaves a constant and consistent “I” at the centre of the remembering. How to describe one’s memories in a way that avoids saying “I remember,” “I recall”—in a language that always places agency with the one doing the remembering? Are all memories stored in the brain, or are they instead triggered in the brain, as I have suggested, from their place elsewhere, “out there”? How about “I stumble across a memory,” or “I pick up on a memory,” or “a memory finds me.” Maybe not these words exactly, but something to suggest that agency is not always mine.

The poet I am due to meet, José Luis, turns up two hours late in our designated restaurant, by which time I am several drinks down. We shake hands. He apologizes for his tardiness; he was delayed returning from Mexico City. I don’t feel like eating again, but José Luis orders pasta. He has a strong smell about him, which I try, and fail, to place. He gestures towards the empty glasses on the table and says, with a smile: “I see you’ve discovered ‘palo y piedra’.” What’s this, I wonder? I am drinking beer with a tequila chaser. He explains that “Palo y Piedra” (stick and stone) is a term used for this combination of beverages. I can understand why. While I was waiting for him I had been entertained by the mariachi band who were playing the restaurant, delivering the usual mix of melodious sorrow and remorse, which, together with the alcohol, and my meditations on memory and consciousness, have gradually rendered me less and less inclined to speech. I certainly don’t wish to talk about poetry, or plans for my anthology, which have ostensibly brought us together. Fortunately, José Luis talks almost exclusively about corruption in the state of Veracruz, the big news story of the moment. He tells me about the shopkeeper he knows who had to close down because he couldn’t pay the protection money that kept going up and up. These people are everywhere, he says, the ones who put about the suffering, and who are the bane of the earth. And their victims, they are everywhere too: the poor people who endure this continuous indignity and oppression, the ones who suffer. In Mexico they pay up or they sell up or they get killed.

I recall—the memory is triggered in me—that in Sicily, in 1983, during the winter that I spent living in an abandoned farmhouse outside the small town of Scoglitti, I used to visit a sea-front restaurant nearly every day. I had become friendly with the proprietor, and one day I dropped by for lunch and these two guys came in, short, thick-set thugs, who spoke for a while with Luca, the owner. After they had left, over coffee, Luca told me that this had been going on for a while and at first he had tried to ignore it in the hope that it would go away, they would go away, but they did not go away, they kept coming back, and although he would not pay them—he would, he said, never pay them—he knew that one day he would just cave in and sell up, which is what they wanted, so the new owners, who would buy the place at a cut price, would be their people, would toe the line and not make a fuss; they would pay up and be grateful for the protection. I do not tell José Luis this story, of course, because he does not need to hear it. In this part of Mexico, such protection is everyday reality. I have a final tequila, and a coffee, with José Luis. As I bid good night to him, I recognise what his odour is: he smells, improbably, of the vestry at St. Edmund’s church in Crickhowell, where I attended Sunday school as a child, and which I revisited a few years ago, at my mother’s funeral.

***

The following day I walk to the bus station and wait for the midday service to Veracruz. The driver ascends, closing the door behind him and carefully sifts through some papers, before attaching them to a clipboard, which he places in the plastic rack to the side of his seat, and releases the electronic door, to allow us passengers on. He is clean shaven with an owlish face, enhanced by round spectacles, his head topped by a tight covering of black curls, and he wears a curiously disengaged expression, a man carrying out a task to which he has long since become oblivious. And yet there is something shifty and spectral about him, as though he were not quite there, and I begin to wonder about those mysterious and ill-defined beings who drift unnoticed amid the human horde, visitors from the ranks of the dead, such as those persons randomly encountered by W.G. Sebald, as he describes them, in the London Underground, at a reception given by the Mexican Ambassador, or at a certain lock-keeper’s cottage, “beings who are somehow blurred and out of place,” and who, Sebald claims, “always…are little too small and short-sighted; they have something curiously watchful about them, as if they were lying in wait, and their faces bear the expression of a race that wishes us ill.” Such beings, according to Sebald, appear on occasion in the writings of Nabokov, elusive creatures from another species “whose emissaries sometimes assume a guest role in the plays performed by the living.”

I recall an episode from one of the Don Juan books by Carlos Castaneda, a writer largely unknown to readers under the age of fifty, but one who exerted an extraordinary influence over an entire generation of youthful mystics and would-be shamans in the 1970s. In one of the books, Don Juan, a Yaqui sorcerer from northern Mexico, explains to Castaneda that some people are not people at all, but what he calls “person impersonators.” Castaneda asks his teacher, Don Juan—not unreasonably—whether the driver of the bus on which they are travelling could be a “person impersonator.” I cannot remember Don Juan’s answer, but am considering the same question now, as we sally forth from the city.

Sitting five rows back in the half-empty bus, looking out at the lush green landscape that furbishes our descent towards the coast, I wonder at all the millions of copies of books that Carlos Castaneda sold before he was unveiled as a fraud and, more interesting still, even after the revelations emerged that he had fabricated his anthropological fieldwork from the confines of his study, thick with the smoke of the joints he routinely consumed, and that he was a fantasist and a charlatan. People continued to buy his books because they wanted to believe in something, because they wanted to believe he had an answer to questions that they could not find answers to themselves.

We pass a roadside billboard with a massive poster of the finely featured, discreetly moustachioed man whom the waiters fussed over in the Posada of Coatepec: he is a candidate in the forthcoming elections. The whole performance on the patio now makes sense, the fawning and running around after him and the ridiculous carry-on with the coat stand. I make a mental note to write down his name but am sleepy, and by the time we arrive in Veracruz I have forgotten it. I wonder later whether he, too, was one of those spectral forms identified by Sebald, whether he, too, was a person impersonator, and had brought an entire cast of underlings with him from whichever realm he had emerged.

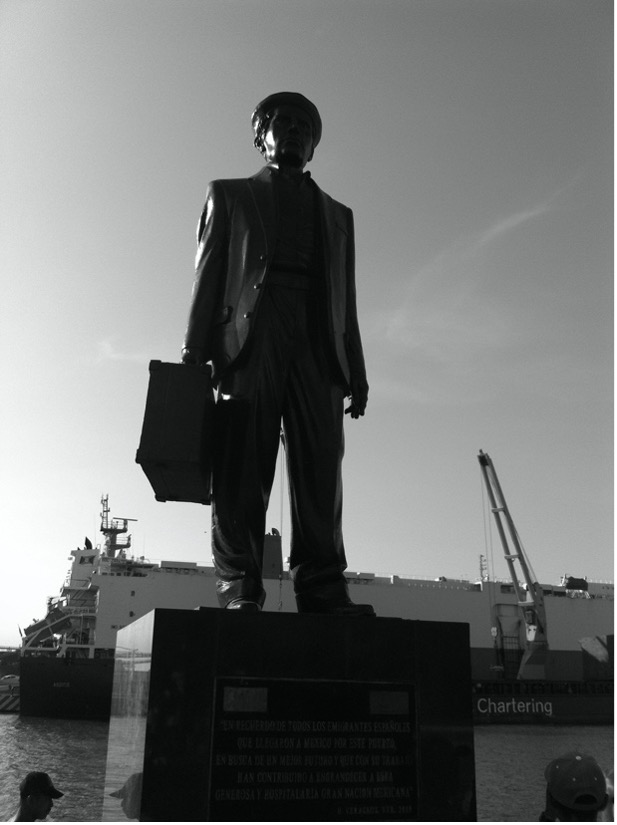

I haven’t booked anywhere in Veracruz so take a chance on the Grand Hotel Diligencias on the Zócalo. It’s expensive, and has seen better times, but I’m only staying one night, so I take it. Back in Mexico City, Pedro Serrano had told me this was the place to be, if you can tolerate the noise from the plaza. I book in, drop off my bag in my sixth-floor room, and set out towards the port, where I take a boat trip around the bay, and admire the statue of “The Immigrant,” a Spanish Civil War refugee standing with his battered suitcase on the harbor front.

Some boys are diving for coins, and I watch them for a while, astonished by the time they spend underwater. I’m thirsty and go to a convenience store for something to take back with me to the hotel. I spend ages deliberating. Am I actually thirsty, or is that a euphemism for wanting alcohol? I consider buying tequila, but do not want a full bottle, which is all they have. If I buy a whole bottle I will drink it. On the bottom shelf, behind the counter, there is a row of unlabeled plastic bottles, always intriguing. I enquire of the shop assistant what they contain, which turns out to be cane liquor: “You don’t want that, señor,” he tells me, with a sigh. Or, at least, that’s what I hear. I head back to the hotel with a modest haul of high carb treats: potato crisps, a pack of chocolate biscuits, a couple of cans of beer and some mineral water. I need to stay sober tonight.

As night falls, I venture downstairs and sit outside the bar attached to my hotel, where, however, the noise is no less shattering. There are now several bands playing in the plaza, which, to use a common analogy, is the size of three football pitches. Nearby is a group of bikers from—according to the inscriptions on their leathers—San Luis de Potosí, who have parked their machines in the southwest corner of the square and planted massive speakers alongside them, from which blasts heavy metal at a volume which smothers most of the other sources of sound, the throbbing bass lines reverberating with an echo in the hollow of my gut. Just as in other countries, the bikers are predominantly middle-aged men, wearing inscribed black tee shirts that barely cover their bulging bellies. They rev the engines of their Harleys, sending out a deafening challenge to the mariachi band playing closest to their patch. There are, however, at least four other mariachi bands sounding off just now, and a larger band for the dancers further down the square. To add to the cacophony, hundreds of birds, occupying the many trees around the plaza, maintain a shrill and maniacal chirruping, flitting frantically from perch to perch en masse, dislodging a rival group from a neighboring tree, which fly off, squawking in complaint, to find another haven. Police sirens and an unremitting blasting of horns from the bumper-to-bumper traffic add to the great commotion. A fresh contingent of mariachi trumpeters arrives to my right, offering a more immediate assault to the eardrums.

This is, quite simply, the noisiest place I have ever been, its orchestral volume rendering the second noisiest place—the Plaza del Castillo in Pamplona on the opening night of the San Fermín fiesta—into sedate chamber music by comparison. But here, unlike Pamplona, there is no particular fiesta to celebrate, it’s just a normal Saturday night in Veracruz. I was told to expect a lot of noise, but nothing could have prepared me for this aural onslaught. It is beyond the tolerable limits of sound, a dense, geological layering of noise upon noise, a sonic assault of massive dimensions.

Outside in the street, a big red Ford truck pulls up, and five fat men pile out. At the table in front of me, a smartly dressed man with European features is writing in an A4 pad. What is he writing? Amid all this blaring, toxic racket, could there be a second scribe, my double, doing exactly as I am doing? Could he, at this very moment, be describing how there is this person seated behind him, a cover version of himself? I conjure with the possibility that he is a spy, inspired no doubt by the short story I was reading on the bus journey down from Xalapa. In “The Wanderer,” by Luisa Valenzuela, the female protagonist seems to enter into or be entered by—effectively the same thing—the novel she is reading, a theme that also appears in Julio Cortázar’s story “The Continuity of Parks,” in which the realities of the reader and the story being read interweave, tilting into one another to create a mesh in which the actual reader, the fictional reader, and the story itself become indistinguishable. I feel as though the man at the next table, writing in his notebook, is somehow vitally connected to my own experience of the evening, just as the protagonist of Valenzuela’s story is infiltrated by a stranger on her flight from Heathrow, who interrupts her reading, and whom she likens to a spy: “The spy reads as we read, undercover, searching in every page for his own reflection and his reflection is there but it doesn’t satisfy him. On the contrary, it enrages him.”

Could it be that the man at the table in front of me, the putative spy, is writing an account that mirrors my own? That he is spying on me just as I am spying on him? More worrying still, if I allow him to enter my account, might his story become my own? But perhaps this is all a delusion, and writing belongs to no one. “Writing,” according to Maurice Blanchot, “is to pass from the first to the third person, so that what happens to me happens to no one, is anonymous insofar as it concerns me, repeats itself in an infinite dispersal.”

Could it be that there is always another, doing exactly what you are doing, thinking your thoughts, writing your story, singing your song? You can resist him or you can be him, but you cannot make him go away for good. He will always be back, like the cat in that old episode of Sesame Street, impervious to expulsion or drowning or kidnap or being fired from the mouth of a cannon; however, you might contrive to rid yourself of that cat, you will always fail, and he will always return.

Most of the tables are filled with Mexican holiday-makers or weekenders, and to my right sits a small, slight gringo who bears more than a passing resemblance to Stan Laurel, and wears a forlorn moustache and camouflage cargo shorts and a tee shirt with an inscription that I can’t quite make out without standing in front of him and peering, which I have no intention of doing. He is talking to his much larger Mexican friend, in English. The Mexican begins every other sentence with the words “one day”, regardless of the construction that follows, and he terminates many of his utterances, incongruously, with the Spanish words esto y esto y esto (“and so on”). One day I crossed the ocean and came to Veracruz and sat on the terrace of a bar listening to a man at the next table talk to his friend or accomplice or partner in crime… one day I this one day I that… y esto y esto y esto.

My double gets up to leave. He reaches down and from the floor picks up a hard yellow hat, of the kind worn on construction sites. This was not in the script. It dawns on me that, like the driver of Castaneda’s bus, he is a person impersonator, posing as a surveyor or building site manager, and in this capacity was busy filing a report. A report on the building under construction or on the weather, or on me. I am not sure I entirely trust his departure. He will not be away for long.

The Mexican who is sitting with Stan Laurel is doing most of the talking, while Stan, who may or may not be listening, nods his head sagely. The other man is becoming animated and his big round face is wet with perspiration. He says, or I think I hear him say, “one day you will see where went the elephant.” Next, he says: “one day you want fuck with me or you want talk up the history of conscious memory”—but that surely cannot be right, I must be mishearing. And then he says, especially loudly, and I hear this for real: “One day she will say I work every day every day every day. Shit! Some days I don’t give passion. Shit!”

The bikers amble by in a large group. They are wearing a uniform of those black tee shirts, black leather waistcoats (or vests as they say in the US) and blue jeans. In the square itself I can see jugglers and clowns and drag artists and con artists and little stalls selling cigars and wooden toys and junk of every possible description.

A very young woman, with a haunted look and delicate features, carrying a child in a sling on her back, comes by selling knick-knacks made from woven thread. The pair to my right, who, I realize now, are quite drunk, each give her a twenty peso note (about one US dollar), the gringo pointing insistently to the child as he hands his offering to the mother, as if to say “the money is for her, and it’s because of her, your child, that I am bestowing such munificence on you.” Alcohol-driven largesse. The woman in the group at the table directly in front of me hisses loudly to catch the waiter’s attention. He ignores her. She tries calling “Joven!” (Young Man!) instead, which works, and he half-turns, careful not to dislodge any of the bottles and glasses he carries with acrobatic skill on a tray held high above his head. The shiny black wooden surface of my table reflects the revolving overhead fan above me, turning the table-top into a spiraling vortex, inviting me in. I stare for a long time into this swirling mirage.

It strikes me—with the gratification that accompanies a rare insight—that I don’t truly know anything, and probably never will, excepting perhaps the smallest details of a single life, things which can barely be summarized, let alone communicated. But at least, in the fragments that are granted me, I have the salvation of continuity, and can enjoy the exquisite tension of the unfinished journey.

Stan Laurel and his friend leave. When I get up to pay, I notice that Stan has left his small backpack leaning against the wall beside his table. I tell the waiter, so he can keep it behind the bar until the poor fellow realizes he has left it somewhere.

Later, I take a turn around the plaza. An old man with no shoes, extremely drunk, takes a slim bottle of cane liquor from his back pocket, swigs the remaining dregs and slings the bottle away with an angry gesture. He then begins one of those hallucinatory boxing matches that some drunks get into, taking swings with his fists, to the left, to the right, and he staggers on, fighting his imaginary enemy.

It is past 3:00 a.m. by now. One of the last performances of the night is underway: a tight-rope walker, who has planted his rope between a tree and a lamppost. He is pretending to be drunk, supping from a cane liquor bottle identical to the one the man with no shoes just threw away, quite possibly the same empty bottle, picked up from the street. The man with no shoes abruptly stops shadow boxing and stares in confusion at the tight-rope walker for a few seconds, before letting loose a string of profanities, and stumbles on his way across the square.

In the breakfast room the next morning I see the little gringo, who no longer looks like Stan Laurel, and ask after his rucksack. He has it, but didn’t know it was me who handed it in. He is grateful, but his display of gratitude is only an excuse to make a few derogatory remarks about the dishonesty of Mexicans. I’m not interested in listening to him, and walk away while he is still talking.

Richard Gwyn is a writer and translator, based in Wales and Catalunya. “They Call Me The Ambassador” is from his forthcoming travel memoir, Ambassador of Nowhere. Richard’s blog, published under his alias of Ricardo Blanco, can be found at richardgwyn.me.

Photos by the author.