SARETTA MORGAN interviews MURIEL LEUNG

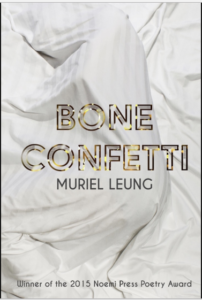

In this month’s interview, Saretta Morgan talks with poet, editor, and academic Muriel Leung about her poetry collection Bone Confetti; queer love; how loss can activate political consciousness; Hortense Spillers; and writing in a state of transition. Bone Confetti was released by Noemi Press in 2016.

*

Saretta Morgan (SM): I feel Bone Confetti asking me to consider not so much the devastating experiences of loss and romance, but the diverse emotional and intellectual landscapes those experiences manifest. I’m interested in “Absentia-Land” as a setting for this work and wondering if you can talk more about what it might mean for one to exist in a terrain of absence? What are the implications of that?

Muriel Leung (ML): It’s interesting that shortly before writing this, my dear poet friend, Chen Chen came to town and we got to talking about the relationship between grief and queer emotionality, a term that Kimberly Alidio examines in queer Pinay identity in her recent poetry collection, after projects the resound (Black Radish Books), and which Chen and I have been obsessed with following her recent reading in LA. I think a committed relationship to literature compels a complicated relationship with grief, to acknowledge its many layers, textures, and responses.

When my father passed away, I turned my grief into rage and a growing political consciousness that made me something of a menace in college. Shortly after, I began to identify very strongly as queer (as in “fuck you”), I cut off all my hair, and I felt this insistent sort of urgency in every action and the imminence of every possible violence. The years following were also my fiercest and most tender years too, oddly enough, and I remember wanting so deeply to mitigate the rage with intense love for another. I think of how grief can make things so precise at times, amplify at others, and thread together the seemingly disparate moments of one’s life so that everything aims at, points at that grief—grief as definition, as language.

“In Absentia-land: A Romance” appears in Muriel Leung’s Bone Confetti (Noemi Press) and was previously published in Gigantic Sequins. Image and text are by Muriel Leung with music composition by Matt Orenstein.

I think of “In Absentia-land” as not so much an absence, but a state of in-betweenness, of transition. I am always feeling too excessively, am too much, and am far too slippery to be settled by a single definition or prescribed way of life. What a strange thing grief permits, the boundaries it erodes, how it can trap you and liberate you all the same. “In Absentia-land” is an after-world where things are constantly gestured to and not yet quite; where the longing for the past and a desire for a better future converge.

SM: Reading Bone Confetti, I felt excited by how you are reframing absence. I understand “In Absentia-land” as a place of insistence on memory, of resisting compartmentalization.

ML: In my cultural and familial upbringing, ghosts are part of everyday life just as one’s ancestors are always with us even when they aren’t physically present. In every social and historical violence, I believe too, the residues of those harms linger far after the events themselves have passed. They take on other forms like PTSD, abuse, disassociation, new economic structures, pervasive military presence, etc. What happens when we apply absence to these conditions? If anything, I hope that “In Absentia-land” is a place against erasure. It’s a miserable-as-hell place, but that’s part of the conditions of refusing amnesia, of survival.

SM: I’m interested in your desire to meet potential violence and rage with intense feelings of love. I think of queer love as having similarly blurring effects to that of grief. But also I wonder: if love is to be our recourse, what should we be able to expect of it?

ML: I agree that queer love is oftentimes blurry, at least for me, because it’s so coupled with grief. I don’t think it’s a balm necessarily in the sense that “love heals all” but that its form seems very much coupled in grief practices. I think so much of our perceptions of love are fueled by loss. When you situate it in terms of social and political grief, as someone who regularly sees the members of my communities brutalized by homophobic, transphobic, racist, and xenophobic violence, those feelings of love feel so enmeshed with grief, fury, and loss that they come to constitute the many textures of its daily composition. It’s the great burden, I think, in queer and trans communities, to always carry love with the possibility of death.

SM: How do you attempt to track practices of love and desire and what they open up?

ML: I feel so ill-equipped to discern what love opens up and what can/not move alongside it. I volunteered for a while as a rape crisis counselor and [we] learned really clear lines between love and abuse in our training. So much of emergency response care in times of crisis requires these clear lines; directness to assist in times of immediate danger. In my own therapy sessions though, I’ve grown less sure about where that line is, which is the difference I think between a moment of crisis and longer-term, sustained care. Both are equally vital, I think, which may seem contradictory, but perhaps that’s the perpetual contention between direct care and our experiences outside of it.

I resent being told I have a false sense of love because I’ve loved an abuser whose love was often weaponized against me. I believe that love was real to them. [To know] that love can exist in such myriad shapes, in the form of harm, is such lonely knowledge, but it’s the best perspective I’ve got right now.

This is the lens that gives me the most room to move, to know how easily things can be re-shaped and corrupted, and where I’m situated in that. Like a science that demands that every response [engenders] a counter-response, so does life persist after abuse. Love can exist in survival, too, though we’ll have to study and grow accustomed to its new and unfamiliar shapes.

SM: I keep coming back to the charge in your poem “We-an After-World Anthem,” to say something meaningful every day. What kind of gesture or utterance is deemed meaningful in a world where unimaginable violence is inescapable?

ML: Traumatized people oftentimes experience little relief. Every encounter is a potential trigger (i.e. turning on the TV, talking to a stranger, taking the train). “say something meaningful everyday” is gallows humor remarking upon the futility of language at times to reassure, to create something so purely hopeful that it should eradicate all former wounds. I think it’s a little funny when, at a loss, people assume various “buck up!” clichés, and I think rather than being mad, I’m a little impressed by how our socially sanctioned ways of caring for one another have yielded so many generic iterations. Like how much time we invest in avoidance rather than engaging with the real hard thing of grief and its silences. It seems so simplistic to say, but I really do wish we could all listen better.

SM: Your responses thus far have reminded me of an excellent talk at the Schomburg Center last year, Standing in Formation. The panelists discuss politicization as a response to loss, framing it as the result of an activated impulse to survive. I’ve often thought of politicization more as a cathartic impulse, or as the result of a need to make sense. Could you talk more about the politicization you underwent as a result of your father’s death?

ML: Thank you for linking the Schomburg talk. I think one take-away from the discussion there is the importance of accountability—to one self, to one’s communities—not just in reparative activities after experiencing violence but exercising initiative in its prevention, in changing the course of how we imagine our relationship to different systems in place—to observe how unreliable and biased they can be against those vulnerable to them.

Perhaps I have always been wary in this way of institutions and other spaces in which I feel parts of me are regulated, but grief makes for an interesting activating agent. What I recalled most, at the moment of father’s sharp decline in health, was how formative of a role he played in my life when it came to language and then later to social justice. How punishing my father was throughout my life; he always ensured that I did everything just right, to stay out of trouble, and never let anyone question the merit of my work. Before I entered kindergarten, he made me write the English alphabet over and over so that I would be prepared in school, but because I didn’t speak a word of English, it meant nothing to me. It was shameful, in my elementary school of predominantly Chinese students, to come into school and be placed in ESL classes, but it was where I spent my first years. So in a way, it was shame that propelled me to learn English and learn it fast. How regretful I am now to have allowed social shame to dictate my first encounters with language. How I wish that I had embraced it, been allowed to embrace it, as a wonderful searching instead. I thought of this memory often in college when my father was passing away. I was on a predominantly white campus, compounded by the shame and anger tied to my invisibility and erasure by white students and the shame bred into me by my father’s sense of rigor and determination to see me assimilate well… and into what? A society that rejected me anyway? Shame is a useless propeller then, and it became clear that something new must take its place.

I think love became a political substitute. But what does it mean to look for self-love at ground zero? I had to wrestle through that alongside so many other students of color during my college years. We organized together at Common Ground, the student of color space at Sarah Lawrence College where every action against racism and misogyny felt like it brought us closer to self-love. And we loved each other, a healing love. I thank everyone who was there that time in my life, who held my grief with me, and bolstered my education of other spaces where I belong, alongside my first readings of Assata Shakur, Gloria Anzaldua, and Grace Lee Boggs, women of color who just survived the shit.

SM: Hortense Spillers gave a talk at Barnard this past spring where she spoke about being frustrated with the assertion of love as it is used to impose dignity with regard to sexual relationships between white slave masters and black slave women in the American South and the Caribbean. For instance, the suggestion that if a slave master and his slave were experiencing feelings of love, then the relationship did not constitute an act of violence, or that the potential for violence was mitigated by the act of love, which presumably offers the slave dignity within otherwise abject circumstances. My feeling during the talk was that Spillers wasn’t suggesting that love did not exist in those circumstances, but that if our concept of love is able to exist within those conditions, it is not a love that can offer dignity under any condition.

ML: I’ve been thinking a lot of your example via Hortense Spillers, of the idealization of love merely as a tool of liberation when so often throughout our history it has been used, blended even, into systems of slavery to permit and excuse so many forms of brutalities. I think of how often people now remark with shock that such a system as slavery could exist, but I think that surprise comes from not knowing how love—when presented in a paternalistic form (i.e. some masters cared for their slaves, treated them like family)—can show us [violence that] at face value does not look like violence. I think people of color, especially black people, know how insidious love, in the form of “good intentions” and liberal guilt, can be. What it cautions for me is the acceptance of love in any simplified form without considering the implications of power that inform every relationship between a person and a system as well as the different bodies that inhabit that system.

SM: This brings me to another resonance I feel between your work and the Standing in Formation panel. One of the panelists asserts a major role of the arts is to be a space where we get to imagine dignity. The language in Bone Confetti feels ripe for such a task (and the reimagining of such a task). What do you feel the language in Bone Confetti is reaching for or imagining?

ML: I hope that, in response, Bone Confetti as a work can be saying, “I love you and–” as a promise to go beyond what has already been socially sanctioned as appropriate love or care. Perhaps the greatest challenge, in language and in any movement towards social justice, is to dream up and perform something that can address the difficult particulars as well as the greater vision of a future. To do both is no easy task, but if we really intend to make the most of this loss, to prevent further grief, to truly love and invent new love where it does not exist, we have to take up this dual labor. I hope that message resonates through Bone Confetti.

SM: What are the texts or reading experiences that have ignited that visceral complexity in you—that have driven you to hunger? Perhaps the language lessons with your father are one example. Are there others?

ML: The works of Bhanu Kapil come to mind, the integrity of her vision and artistic practice, as well as that of my mentor at Sarah Lawrence College, Cathy Park Hong, who exposed me to new ways of writing, and the Asian American women writers who continue to do that work. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Trinh T. Minh-ha, Gloria Anzaldua, Angela Davis, Grace Lee Boggs, Audre Lorde, Assata Shakur—all of whom foregrounded my literary and political education. There’s also Kara Walker’s silhouettes and Wangechi Mutu’s chimeras. Kerry James Marshall, whose retrospective I recently saw twice at the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Art. I felt my heart rise up in my chest each time, seized by how much time and thought and feeling Marshall had devoted to each work’s portrayal of black life, the enormity of his references, the range of his forms, and his care. How unflinchingly his work always engages black life. I want to remember that lesson: how to be loyal to one’s values and communities in the face of the shifting and turbulent tides of history and its circumstances that tend towards erasure.

And also this: my mother in NYC is three hours ahead of me and because of our odd working hours, we always miss each other. I texted her on Mother’s Day since I knew we’d miss each other. I wished her a happy Mother’s Day, and then said, “Thank you for always believing in me and pushing me to be the best.” To which she wrote: “Do something is best for your life.” I cried in my car when I read it, thinking of how long it has taken for someone in the family to [offer advice] that is not a striving for a goal that isn’t achievable. How my parents’ designs for the future began as arduous labor, evolved into survival, and arrived now, in my mother, in the form of “your life.” I don’t know how to even begin describing this gift, but perhaps only that it had always been there, before it was written, and it took some time for it to come.

*

Muriel Leung’s collection Bone Confetti was released by Noemi Press in 2016.

*

Saretta Morgan is a text-based artist living in Brooklyn, NY.

*

Video credit: “In Absentia-land: A Romance” appears in Muriel Leung’s Bone Confetti (Noemi Press) and was previously published in Gigantic Sequins. Image and text are by Muriel Leung with music composition by Matt Orenstein.