Years ago, I wrote that seekers of all stripes—journalists, philosophers, scientists, mystics—are chasing the same elusive thing: something like truth, understanding, a fully integrated perspective, awakeness, untangling. We just ask questions in different contexts, modalities, and microcosms.

At the time, I identified deeply with journalism as a way to grapple with and understand the world. I still believe that journalism, when done sensitively, can dismantle our fixed ideas and widen our awareness. Reporting certainly can have a profound impact on the one doing the reporting, and on the one reported on—often a traumatic one. It has a profound impact on the one reading, sometimes subliminally, as it feeds constructed projections and conjectures of unseen spaces and people.

But, over time, I grew disillusioned by the limitations of the field. I pushed my news features to the very edge of what they could be and raged when my wonderings on truth were edited out. I discussed the vacuousness I sense around most mainstream journalism with Nigerian photographer Rahima Gambo. “It is like journalists don’t feel the spaces they enter,” she said, “if they felt it, they would change. Their narratives would change.” Theorist Ranjana Khanna wrote on “textualization, and the violent event of imposing a way of being on the world.” She was writing on psychoanalysis, but journalism also often felt like that. Media aspires for “objectivity” but it maintains its center in the West and refers constantly back to an assumed “normal,” which is itself subjective.

While in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo last year on a fellowship from the International Reporting Project, I was simultaneously reporting and tussling with these questions about journalism, narrative, and truth. As a journalist I have pushed back against simplified portrayals of places; as a writer I have addressed these questions directly; but as a photographer I kept my work largely hidden for a long time because all I knew was what it was not—not documentary, not reportage.

While I respect excellent photojournalism, I find most photographs within that paradigm follow prescribed, explanatory narratives and are, ultimately, inane and boring. I have a visceral rejection of work that seems to say only one thing. It feels shallow. It feels like it is missing the whole point, even when the facts are accurate. It feels sometimes like a violent flattening of the world into pre-determined frameworks for narrative, a selection and distortion of reality to fit into something expected and certain.

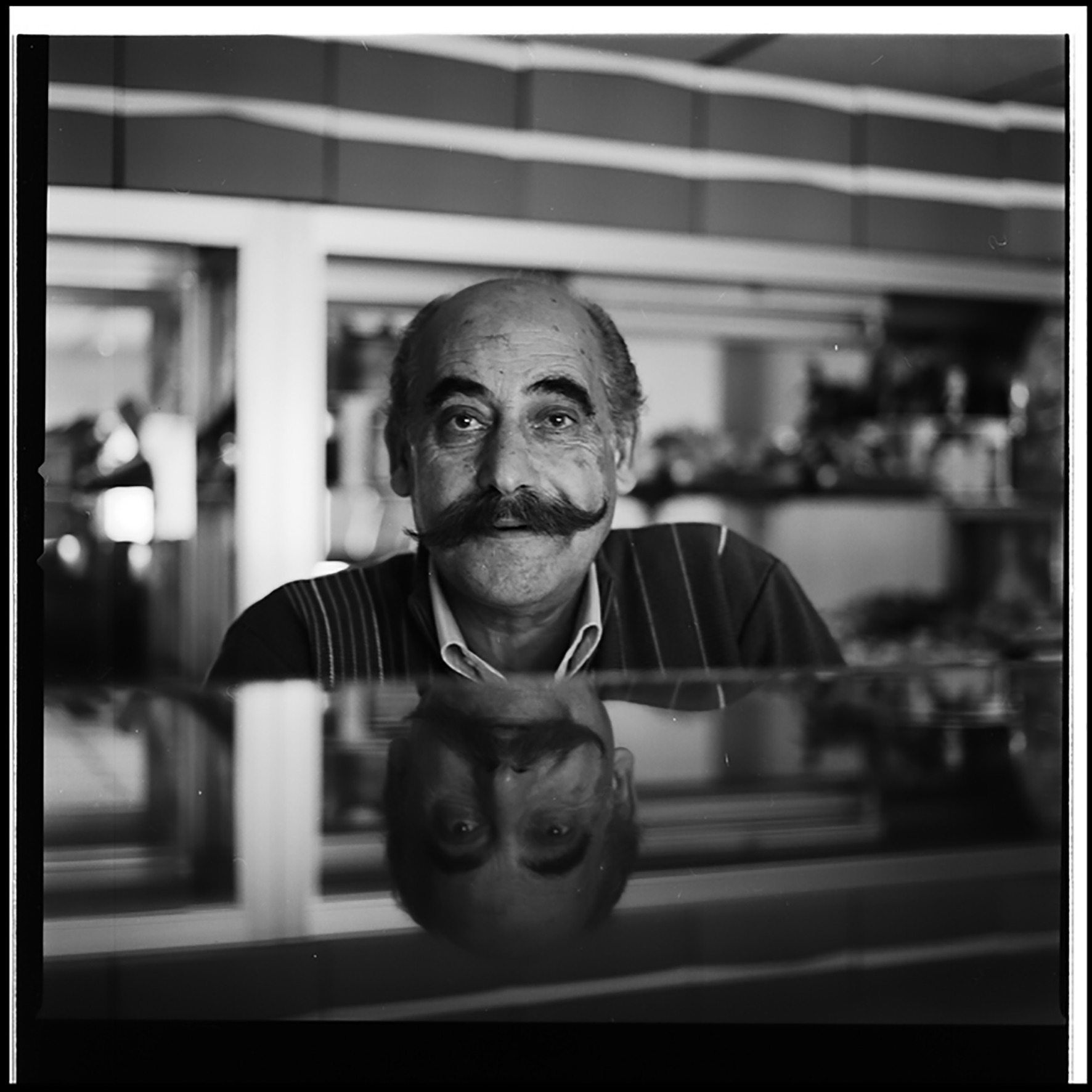

My photography reacts against and ultimately rejects this. It is largely a way for me to visualize and process shifting emotional states. And feelings, like photographs, are in constant relationship to the tangible, visible world. “Cities are this, stone made suddenly alive by our emotions,” Italian novelist Elena Ferrante wrote.

I shot this series on the sidelines of my reporting. I shot compulsively, with no intention. It is a soft conversation between my eyes and the city. It is a counterbalance, an exploration of dismantling narratives to make something nonlinear, something nonliteral but true. Is it possible that in saying less we can say more? That the ephemeral contains more than the thing itself? Or perhaps it is that the thing itself always contains something ephemeral.

In photographing Goma, I wanted to let the city rest. I wanted to explain nothing, to make photographs that do not try to document or argue anything. Just look, lovingly, at a place. I wanted to photograph the in-between. The poetic nothing. Just a street. Just the rain. Just a place. Just a city. Like any other, but different from every other, because no place is like any other. I wanted to work with beauty not as something plastic and reactionary that denies the pain of a place, but as something integrated that encompasses duality and celebrates details, taste, and specificity.

“It is impossible to go right up to reality. Between us and reality are our feelings,” wrote Svetlana Alexievich, the Nobel Prize winning investigative journalist. These photographs are about Goma. They are also, like all photographs, about the photographer, about me. Along with the details I find beautiful in this place, there is my fatigue with assertion and my attraction to obfuscation. There is blurred vision and my probing for something both deeper and less invasive than facts. There are my questions of how to metabolize pain and how to reconcile it with a glittering world.

Allyn Gaestel reported from Goma with support from the International Reporting Project.

She is a writer, journalist and photographer based in Lagos, Nigeria. She has exhibited her photographs in Nigeria, Germany, Brazil and the US. Her writing has been published in print and online at The New Yorker, The Atavist, The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, Al Jazeera, The Guardian, The Atlantic, Nataal, Intense Art Magazine, Moon Man Magazine, etc. Find her at http://allyngaestel.com