By MICHAEL KELLY

Orson Squire Fowler was a man convinced of the links between physical shapes and structures and all aspects of human health. His primary interest was the shape of the human skull and its relation to human intellect and emotions. Along with his brother Lorenzo, Orson traveled throughout the United States in the 1830s and 40s and beyond preaching the new science of phrenology and publishing dozens of books, pamphlets, and magazines on the topic. Along with their partner (and brother-in-law) Samuel Wells, the firm of Fowlers & Wells was the leading publisher in the fields of phrenology, water cure, mesmerism, psychology, phonography, and other health and hygiene movements of the nineteenth century. The most famous product of their press is the second edition of Leaves of Grass (1856), but that’s another story. Through the tireless efforts of Fowlers and Wells, phrenology became part of the American cultural landscape. Edgar Alan Poe, Walt Whitman, Mark Twain, Louisa May Alcott, Herman Melville, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and William James are just a few writers who either had their heads examined or commented on phrenology in their work.

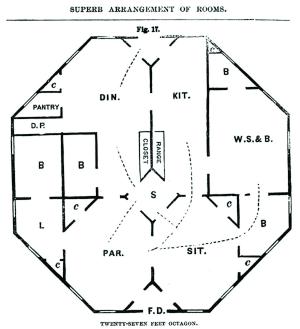

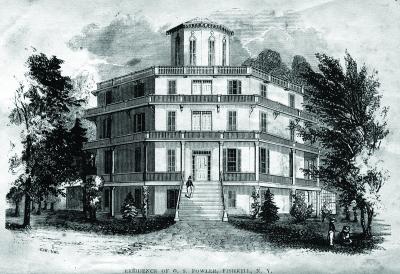

To a mind as creative as Orson Squire Fowler’s, the leap from phrenology to architecture was a logical one, especially when he began building a home of his own. His quest for self-improvement and self-sufficiency led him to explore new directions in home design and construction. In 1848 he published the first edition of A Home for All, which opens with a simple declaration: “To cheapen and improve human homes, and especially to bring comfortable dwellings within the reach of the poorer classes, is the object of this volume—an object of the highest practical utility to man.” In spite of his concern for the poor, throughout the book Fowler argues for improvements regardless of cost because “improving home facilitates, aids every other end and pleasure of life, while scanting it scants all.” The whole of Fowler’s book is a curious blend of pragmatism, self-sufficiency, and excess. Why build a one-story home when four stories are better? Why limit yourself to a handful of rooms, when more rooms will provide more space for exercise and play and guests? “My own house has sixty rooms, but not one too many.”

Orson Squire Fowler. A Home for All or, The Gravel All and Octagon Mode of Building. New York: Folwers and Wells, 1854

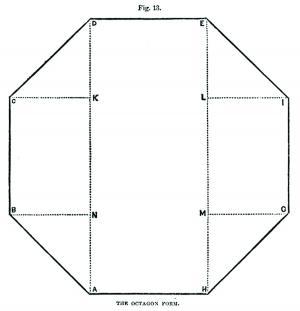

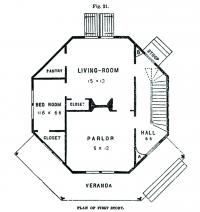

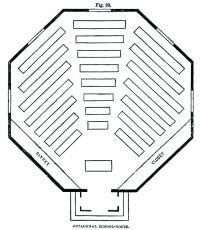

The foundation of Fowler’s argument about octagons is his mathematical calculations that demonstrate how an octagon encloses a greater area than a square form with the same amount of building material for the walls. The octagonal shape also provides better natural light, is easier to heat, and stays cooler in summer. Beyond the economy to be gained in the octagon form, there is also an aesthetic argument against the square. Fowler declares that smooth, spherical forms are more beautiful than angular forms: “Hence a square house is more beautiful than a triangular one, and an octagon or duodecagon than either.” Once one accepts Fowler’s findings from both practical and aesthetic grounds (as if the two were not necessarily one and the same), there is no end to what can be achieved on the octagonal plan. Fowler suggests plans for octagonal schools, churches, and barns in his book.

It is a testament to the popular influence of O. S. Fowler and his publishing firm that there was a craze for octagonal construction in the mid-nineteenth century. While many fine examples of octagon houses no longer exist – including Fowler’s own sixty-room home in Fishkill, New York – several examples still survive. Sixty-eight octagon houses are included in the United States National Register of Historic Places, some of which are now open as museums. The Octagon at Amherst College – originally the Woods Cabinet and Lawrence Observatory – was built in 1847-48 and remains an outstanding example of Fowler’s principles.

Michael Kelly has been the Head of the Archives & Special Collections at Amherst College since April 2009. He has curated exhibitions on the Victorian bestseller, Charles Brockden Brown, James Joyce, Emily Dickinson, ornithology, and the history of scientific illustration. He is currently wallowing in the world of nineteenth-century publications about fossils.

[Purchase your copy of Issue 02 here.]