Reviewed by TERESE SVOBODA

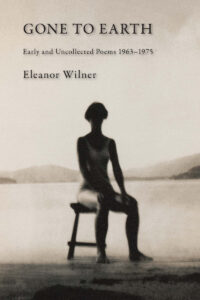

Eleanor Wilner, a recipient of the 2019 Frost Medal for distinguished lifetime achievement in poetry and MacArthur-winner, had to be coaxed to publish her first collection at age 42. Arthur Vogelsang, her co-editor at the American Poetry Review, “threatened various forms of physical harm if I failed to follow through.” Her reluctance, she says, was “probably a universal fear of rejection but intensified by a woman’s trained reluctance to put her own work forward.” The skid marks in resisting publication, even in Gone to Earth: Early and Uncollected Poems 1963-1975, Wilner’s ninth book of poetry, are further evidence of such modesty. On the acknowledgments page, Wilner includes an excerpt from a poem by her then-young daughter, begging her mother to publish. This is followed by “To the Reader,” a note which assures readers that the poems “belonged to the realm of imagination and not to the world of opinion,” then an italicized eight-line epigraph ending with “she much preferred / what she could not afford: / the luxury of words and light,” and a prelude poem, “Ritual,” set in prehistoric Africa, mourning the muse, “the blackened stone / that once poured fire from its heart.” Only then, a page later, does the book begin, all poems fully fledged.

Gone to Earth is one of two inaugural volumes in a series from Crooked Hearts Press celebrating the work of older women. In the book’s first section, the speaker in “Reveries in an Old Dawn” asserts that “I’ve always been… a poet of senility,” a “superannuated nightingale,” and “a faded Andromeda whom monsters no longer bother to visit.” This, in a poem written in the author’s thirties? More accurately, a few lines later, the speaker explains that she has “obsessions untroubled / by the need to accommodate them to those / of others.” Think early Adrienne Rich, with touches of Yeats and Auden but energized with concern for social justice. The poems in Gone to Earth date from years when Wilner and her husband were raising a daughter, teaching at a Black college during the Civil Rights era, witnessing the “I have a dream” speech in Washington, and demonstrating against the Vietnam War. In an interview with Harvard Review, Wilner says the period was a time “when the ethical imagination, freed from self-concern, had become more and more a witness to what we had been trained as a nation not to see.”

But she is hardly polemical. “Admission Paid: Fort McHenry and Other Shrines” is a snapshot of American Studies wrought very subtly with the political. Children are photographed astride a cannon, a family meanders through George Washington’s bedroom with Martha’s cap flung on the bed, with “the enemy’s coat the red in your eyes, or your own blood.” The poem ends invoking that other great Eleanor, with Roosevelt’s “dead voice, flat on tape” that “tells over and over / (till the grounds close) / what horses her children used to love.” Were they also the cannons the children ride in the opening?

Similar in restraint is “For a Russian Writer in Exile.” Set in an echt Russian winter with frozen laundry and buried onions like “the white faces of the dead,” its second stanza asserts the writer’s despair after posting a letter inside a mailbox in which history’s “tossed a burning match”; the third stanza features the poet’s work as marginalia written around another writer’s text; the fourth and last, his suicide: “He had been swinging a long time.” Wilner’s genius lies in holding both the season and the tragedy, the impersonal and the personal, in counterpoise. She does not let the image of the hanged man close the poem.

April

was outside in the air; it entered

when they threw the windows wide, as if

that were all

that had been wanting.

Plath, five years older, died by suicide the year Wilner began collecting these poems and had very different preoccupations. The ego, as Wilner has posited elsewhere, can be blinding. Wilner tends to take the widest possible view, something confessional and post-confessional writers eschew, chewing on as much of the personal as possible. “I began using the word ‘transpersonal,’” Wilner says in a McSweeney’s interview, “as a corrective for T. S. Eliot’s mistaken word ‘impersonal’ for the role of the poet in the making of art. ‘Impersonal’ implies a rather majestic detachment, while ‘transpersonal’ indicates a commonality.” Her poetics are in the tradition of the great Russian poet Osip Mandelstam, who said he was interested not so much in “personal memory but in cultural memory.” Wilner’s favorite pronoun “we” gestures immediately toward the collective and the mythological, an embrace of the human race that in her work includes myth’s made-up heroes: Daphne, Icarus, Eros, Psyche, and many others, in the context of man’s greatest desires and ambitions. Her later translations of Euripides show traditional, mythical heroes as ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances. As Tony Hoagland said of her: “she rides the big waves.”

In “Ariadne’s Prayer,” Wilner invokes the Minotaur, “his great horned head snoring on stony paws,” and suggests we “learn from the sun how to help him doze / in the dazzle of noon.” But she doesn’t allow the reader to loll about, admiring his repose. She writes: “then, go with him, / let him chart your passage through the night / whose hoofs know every stone.” For Wilner, the past contains truths that we can use—that we need—for understanding our contemporary situation. “Why shouldn’t hindsight create its own version of what mattered most?” she asks in an interview. For her, the Constitution is no tablet wrought in stone, and certainly not when it makes no mention of women.

“You write about things you don’t give a damn about,” Richard Hugo said with regard to Wilner’s interest in the mythological. She justifies her choices in the poem “What do myths have to do with the price of fish?,” beginning with the personal: “Nothing, anyway, stops time so / tell it over try to make it serve us / better.” She appeals to what’s beyond history as rationale: “where America / is not what is the matter but something older, / deeper, that has everything to do with us.” And finally, she celebrates the earliest stories: “having eaten of the Tree / of Knowledge, this time we’ll pick / the other tree and eat the fruit of life.” Those two last lines are the only direct overlap with her work in later books, showing up in the long poem “Sarah’s Choice,” which features a Sarah faced with the possible sacrifice of her son Isaac. If only, Wilner suggests in its outcome, she had had a say.

The last poem, “Olympus and the End of Winter,” posits most of the gods dead or destroyed, with only Psyche and Eros surviving, with even their daughter, Joy, having “grown and left” for the lands below. Near its end, horses look up with their “fathomless eyes” as if they understood the centaur Chiron’s half-human predicament “and [have] gone on grazing.” Acceptance. The poem closes with the solemnity of a filial blessing: “Of Joy no end is given.”

To the British, the phrase gone to earth means a hunted animal that is hiding. In Wilner’s “To the Reader,” her reticence to publish is explained as “a form of creative survival not unlike… the hibernating creatures in winter or the fox gone to earth in a world of hunters.” But gone to earth seems also to refers to what happens to the marble in her poem, “Be Careful of What You Remember,” published in a previous volume. Its tombstones are “unquarried” and returned to the earth from which they were taken, the land restored until “young trees grow thick again on the slopes.” Thus Gone to Earth seems to refer both to further hiding her light, and its final disappearance, as it were, in recycling. As she says in her interview with Princeton University Press with regard to Before Our Eyes, her new and selected poems from 1975–2017, “I’ve had a long and fortunate life, darkened by history but illuminated the whole way by poetry.” Wilner is only 85; Stanley Kunitz published his last book at 100. Gerald Stern, a mere 95, published a book last year. Barring her unwarranted reticence, hope remains for more.

Terese Svoboda is the author of twenty books of fiction, poetry, memoir, biography and translation. Theatrix: Poetry Plays (Anhinga Press, 2021) is her most recent, and two novels are forthcoming.