Anna was slow to do the math. B saw it instantly—what might be left after everything else melted away. White captions flickered in the dim exhibit hall.

B had turned thirteen that fall, ready to join Anna on a trip that was part research, part treat and adventure, the first time they had left the country together, alone. A few days in Rosario (a university lecture, an interview with a playwright), the long bus to Buenos Aires. Invited to contribute to the itinerary, B asked to see glaciers; Anna booked a half-day trek across the ice.

Passengers all around them had clapped when they landed in El Calafate. “That’s so sweet,” B said, joining in. Anna clapped, too, hoping it was thanks, not bald relief. The tiny airport was rapidly navigated. Advertisements lined the baggage claim, placed to catch a teenager’s eye. “They have an ice bar at the ice museum,” B said. “Can we go? There’s a free shuttle from the tourist office.”

“Of course there is.” Excursions all over the country relied on convoys of small white buses, as operators maneuvered their charges to the edge of the penguin colony, the precipice, the falls. A shiny museum on the outskirts of town would naturally offer visitors a lift.

El Calafate’s main street had an Old West touristy feel, boutiques and restaurants and dust. It could have been Oregon, maybe Colorado, only colder. Signage in Spanish, menus offering roast Patagonian lamb, but also fudge shops, t-shirts, plastic souvenirs. Their hotel was a row of storybook A-frames, bright green cottages behind a nondescript building that held the office, breakfast room, reception. B claimed the upper floor, with its high-up window that took in most of the town and angled walls that made it feel like a secret fort. Anna slept downstairs.

The name change came a few days before their departure, an unexpected assertion from a quiet child. Just B from now on. Anna wanted to give the request its due weight, yet not go overboard. She and Paul had debated so many alternatives—Benjamin, Beatrice, Bobby, Becky, Barbara, Bernard, Belén—before the baby was born.

“Bzzzz. Like the insect?” Paul asked.

“No, like the letter,” B answered. Hands folded, face serene.

“That’s not the best grade.” Paul looked to Anna with a half smirk that might have marked a joke, might have been a plea for help. Anna wanted to smack him.

“I don’t think—” Anna began, then stopped. She felt brittle, exposed. Their child had given them something big; they needed to return the right answer.

B said simply, “It’s something to fall back on. Plan B.”

Paul relaxed into his chair. “Fair enough.”

“Of course, good thinking,” Anna agreed.

And that was that. Anna expected further discussion—reasons, intentions, other changes to follow. None came. She didn’t pry. And B didn’t ask to back out of the trip, still bubbled with excitement as they refined their plans.

In the last year, B had grown two inches, limbs and torso suddenly long. Never one to care about clothes, now B exulted in thrift store finds, vintage garments in blues and greens and browns; it was a creative challenge, and a new point of principle: reuse, renew. Viola practice remained spotty; homework was still pointless. “Is this when kids take up veganism?” Paul asked Anna, but that hadn’t happened yet.

B’s moods didn’t swing, exactly, but they all felt intense. Anna never knew when her thoughts would be welcomed, or when an observation might land as a patronizing intrusion. Flattered that B wanted to travel with her, she hoped she could get it right.

The name conversation came back to Anna when they visited the ice museum, a stark, trapezoidal structure that might have dropped from a spacecraft. Inside, beyond a modest gift shop, shallow ramps led to the hushed exhibits. Anna read with attention, harvesting facts before they saw the glaciers up close. A glass case held a dog harness, a compass, water-stained navigation logs. Vintage film loops of harrowing expeditions narrated in crisp British accents ran uninterrupted, and an animated video explained moulins: vertical shafts formed by water percolating through cracks in the ice. Per-co-lar, the cartoon voice enunciated. Anna thought of her grandmother’s coffeepot, bubbling and hissing. Her feet ached with the step-together, step-together dance of reading the exhibit labels, her shoes an uneasy compromise between comfort and professional gloss.

In the main gallery, floor-to-ceiling photos introduced the glaciers of the world. A sign proclaimed: “Las enormes Alturas del Himalaya, la cordillera de Karakorum o el Monte Fuji con su corona blanca, son algunos de los lugares donde el hielo dice presente en el gigantesco continente Asiático.” El hielo dice presente. The ice, alive, called out, in Spanish, I’m here. By contrast, in blue ink below, the English: “The highest altitudes in the world in the Himalayas, the Karakorum or Mount Fuji are a few examples of glaciated areas in the vast Asian continent.” No frills. Presente was how any high school student might respond during roll, but Anna now recalled an activist colleague who hollered ¡presente! whenever revolutionary heroes were evoked. His voice echoed in her head, a mourner at a rally.

“¡Presente!” Anna repeated, too loud, shouting into an empty museum.

B was staring at the next panel, shoulders drawn back, eyes grief-stretched and angry. Anna slid closer—step-together, step—to read for herself. Read it again, lips moving. It was all there for her to see, bellowed in black and blue and white in both languages she could read. Arctic ice might be gone by 2030. “I’ll be twenty-seven,” B said. “Twenty-fucking-seven!”

It wasn’t a surprise, or shouldn’t have been, yet Anna felt the iceless future as a blow. She had to sit down. She’d never used B’s lifespan as a yardstick, never calculated the time remaining as such a simple sum. Now that bleak future slapped her. What would happen to them? What would happen to B? Her mind went blank, confirming a fear that she was as far behind as B often claimed, mired in her outdated manuscripts and tedious meetings as if nothing would ever change.

Anna fought to sit upright as the museum bench folded her into a slouch. Breathe in. Hold. Breathe out. It seemed a long time before B settled beside her, touched her shoulder. “You okay?”

“Yes, thanks.” Mixed affection and relief nearly swamped her. Anna raised her head to look at B. “It’s just. . . a lot.”

“Yeah,” B said, not quite meeting her eye. As exhausting as the effort to keep up with B sometimes was, Anna needed to do better. Find a way to offer comfort when she doubted her own way forward. She found herself increasingly afraid to overstep, but what if she erred in saying too little?

“You’ll have to fall back on yourself, be your own plan B,” Anna whispered, then shuffled her feet, white noise after the fact, hoping B hadn’t heard the glib suggestion. A sudden tickle in her throat made her cough. It was an excuse for tears, anyway—no, not crying, choking on air.

B nodded slowly, almost amused, then fished a hard candy out of a jacket pocket. “Will this help? It’s not a cough drop.”

Anna winced at the loud plastic crinkle as she unwrapped the candy. The sharp blast of sugar and citrus made her forehead sweat, but the syrup in her throat was soothing.

B looked around the gallery. “This is all—”

“Museum-quality ice,” Anna finished, wanting the words back as soon as they were out of her mouth. Another stupid thing to say in the face of that gut-punch arithmetic.

But B was considering the idea. B had always been practical, focused on the problem at hand. “What makes something museum quality? Just that it’s rare?”

Anna’s teaching reflexes perked up. She had been busy with museums and framing since April, when she’d devised a library exhibit on Southern Cone travel writing. Later, inspired, she’d re-matted her mother’s antique botanical prints. Shopping for frames, claims of museum-grade quality met her at every turn; the huckster’s phrase reminded her of the pitches for commemorative coins found in the slick pages of Sunday inserts. “Funny you should ask. You know, museums aren’t strictly repositories of the well-crafted. Sometimes it’s just what got saved or repaired or misplaced.”

“Mo-om!” But B was smiling, having endured years of ham-fisted allusions and impromptu lectures. The two-syllable protest was a formal objection only, no malice. Still, the force-field surrounding B was far too prickly for Anna to risk a hug.

B shifted on the bench, tense as a spring. “Someday, ice might only be in museums. Like a zoo. All those sad, neurotic tigers.”

“As in, what are we even saving it for?”

“Exactly.” B took a breath as if to speak, then reconsidered. The anger seemed to come and go, like waves. “There might not even be museums in a few years.”

“Oh, I think—”

“Never mind,” B said, sharply. Then, standing up, “Let’s check out the ice bar.”

Anna smiled. “That’ll look good on my trip report: took kid to bar.”

“It’s a museum bar, not a real bar,” B said, holding out a hand to help Anna up.

The drinks were real enough, the access protocol. They stepped into a busy anteroom supervised by a tiny woman in wire-rimmed glasses who explained the rules. No reservations required, but entrance at posted intervals. No opening the door willy-nilly, letting the cold air out. Drink as much as you like but when your time’s up, it’s up; twenty-five minutes. Keep the mittens on, cold can be deceptive.

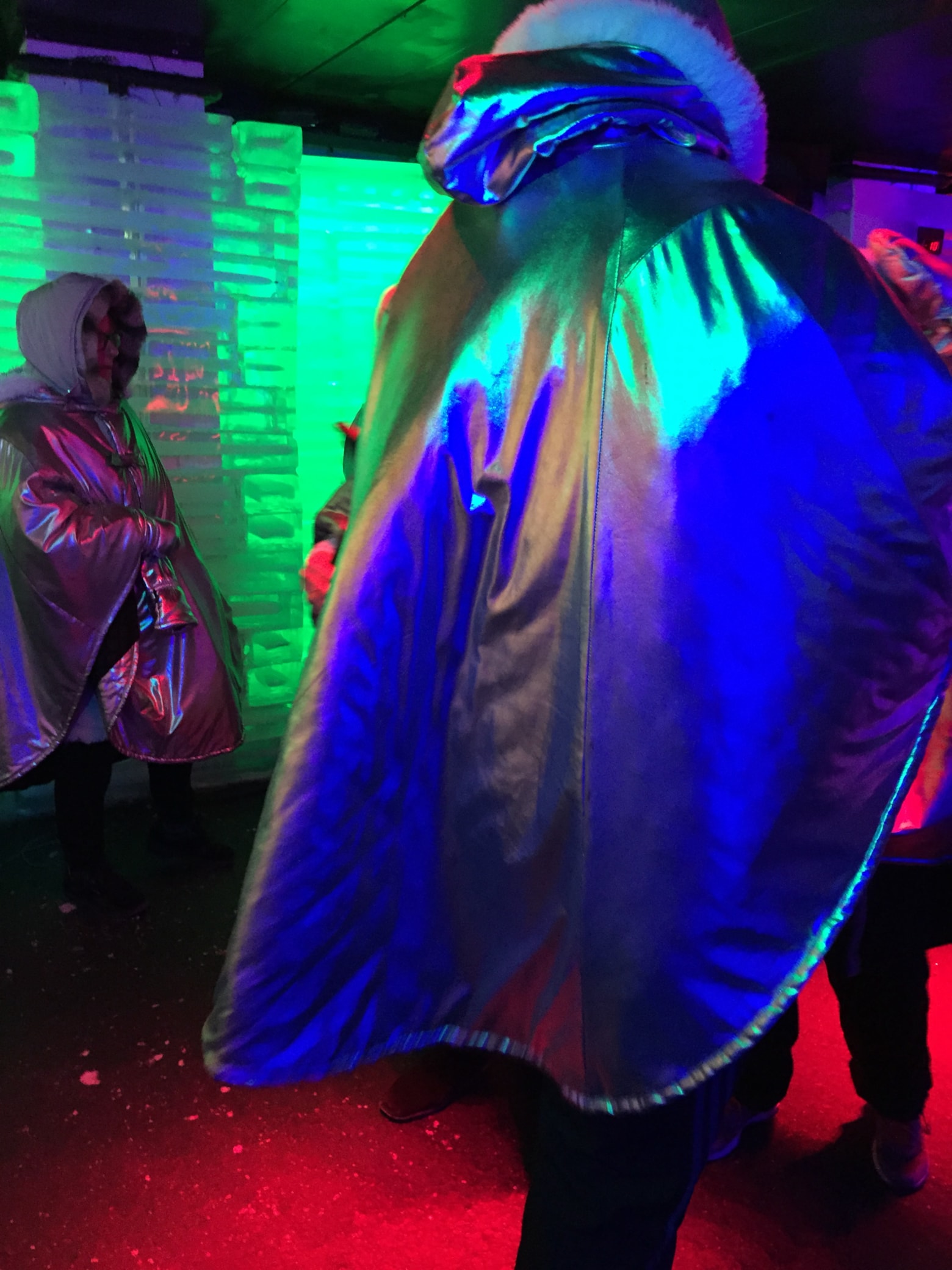

The airlock doubled as a locker room. Anna and B donned silver ponchos, lost their hands in mitts the size of hams. They adjusted their hoods, shinier, fluffier versions of the tunnel-hoods popular on winter parkas in the 1970s (Anna had a navy blue one, orange inside, from Sears). The guide counted down from ten, raising her voice and clapping her hands until most of the group joined in, then opened the door.

The museum halls had been quiet, nearly empty. Not so the bar. Anna’s first impression was a wall of light and sound, flashing lights magnified and repeated by the ponchos, people packed shoulder to shoulder. The thump thump thump of dance music filled the space. Cram in all the fun you can before they kick you out.

An ice fireplace loaded with frozen coals glowed pinky orange, lights flickering across the hearth to mimic flames. The barkeep looked faintly amused, superior without being snide. He poured the drinks on offer, answering questions about the bar’s construction, the sky-high cost of its fueled refrigeration. One group after another took pictures beside the imaginary fire, then under the neon logo on the wall. Cameras and phones passed hand to hand—“Could you take one of us? Oh, and get my sister in the frame!”

“This is one of the weirder tourist attractions I’ve been to,” B shouted.

“Me too,” Anna agreed. They clutched their ice-cast tumblers with both hands, distrusting the ungainly mitts to grasp the thick, slick cylinders. B drank Coke, Anna limoncello—slow sips of sticky sweet. The shots were small, chilled by the surroundings and chilled further by the ice tumbler—no need to order anything on the rocks. Anna thought incongruously of the rocks under the glaciers, the grit and gravel they’d read about, drawing sunlight, concentrating heat.

“I thought it would be icier,” B said. “I thought it would really be built out of ice. Like a real igloo. This is more like ice paneling.”

“Not even that.” It was a metal framework bathed in frozen water, a giant air-conditioner, the walls of tourist-cooling ice sculpted by climate-warming fuel. No wonder they were so fussy with the airlock.

People were dancing, self-conscious but having fun. Anna hadn’t danced in public in a long time. She wanted to twirl, tilted her head in invitation. “We could . . .”

B snorted. “No chance.”

Anna flapped her poncho, a matador brandishing a cape. It didn’t matter that it was more of a replica than a real bar, or that she was with her thirteen-year-old, not on a date or with a group of friends. And it was only half public—no one knew them there or ever would. In costume, everyone looked alike, and similarly foolish, dancing or not. Anna felt her muscles loosen, hoped it was the movement, not the booze. She shimmied, took another sip.

B watched for a few beats, then joined in after all. Anna raised an eyebrow. B said, “Never let a mom dance alone.” Anna laughed. B’s movements were jerky, almost methodical—Anna wouldn’t criticize, couldn’t help noticing—yet B seemed to be enjoying the game.

People drank steadily, happily. No one made a point of winning the all-you-can-drink challenge, save for a guy in a blue watch cap determinedly slamming shots. His hood pushed back, he looked rakish, the one guest out of uniform. He also looked like he’d been there a while, as if this wasn’t his first time around. Anna was surprised the bartender didn’t cut him off, all-you-can-drink be damned.

The music pulsed against the time limit. Drink in one hand, phone in the other, Anna recorded a video, thinking she might watch it later, her own dance mix on repeat. “I just wanna feel this moment, this precious, frozen moment,” the singer wailed, milking the sweet sadness of the pop anthem, toned up with an electronic drum line that pushed Anna’s hips into a decided swing. Anna found herself wanting one of the big-hair power ballads of her high school days, until she picked out the first notes of a gorgeous weeper, Juan Gabriel at his finest. She started to hum, half singing along, saw she wasn’t the only one. “Siempre en mi mente . . .” All around her, soft smiles of nostalgia. Buoyed and reassured, Anna reached out her free hand, ice tumbler crooked in her elbow.

And came up empty. B had stepped back, out of the swaying clump. Not annoyed, but not part of the group. Anna pulled herself away, too. This was B’s treat.

B didn’t chide her for singing, moon-eyed and middle-aged. Nor were there effusive thanks when Anna came to her senses. Just a sly salute with the ice glass, no need to say anything out loud.

One more dance number, then the music stopped. It wasn’t quite musical chairs, but there was a noticeable dip in volume, a shuffled jockeying for space. The light became harsher. Anna saw Watch Cap being helped to the exit before she lost track of him in the crowd. The air lock again, ten people at a time swept into the anteroom, then hustled out the door. B cadged a last splash of cola before they had to go.

Outside, they watched the shuttle pull away. Anna kicked herself for not having hurried. Now what? A woman in a crocheted shawl smiled in sympathy. “It was full, but they’ll send another,” she explained. A younger woman beside her stared after the departing bus. B slumped onto a rock, worn out and irritable at having to wait after the strange intensity of the bar.

“Thank goodness it wasn’t the last one,” Anna said.

“The last one?” B sounded panicked.

“Not the last,” Anna repeated.

The woman shuddered. “Imagine spending the night out here!” She shook her head in a broad arc that took in the bare gravel of the museum grounds, the mountains ranged on the horizon.

Anna shuddered agreement, hoped (silently) the woman was right about the second bus. B looked so small, so tired. Anna felt the happy strangeness of the ice bar slip away and moved to fill the quiet. “An interesting museum. What did you think?” she asked. B shrank a little smaller, hearing Anna in interview mode. Not the effect she’d intended, but it was hard to stop.

The woman moved her shoulders, noncommittal. “Fun, but expensive, no?”

“For sure. Still, I found some of the exhibits very powerful.”

“My niece and I only visited the bar. We didn’t have a lot of time.” The woman was apologetic.

“The bar was cool,” B said, still on the rock.

“Yes, it was,” Anna conceded, taking the hint.

“Plus it was fun seeing you dance,” B added, unexpectedly.

Anna grinned at B. “It was fun dancing.” She hummed a little of the tune still running through her head. Pulling her jacket closed against the wind, she walked the few steps to the edge of the gravel for a better view over Lago Argentino, counted the pink specks of flamingoes in the lagoon. “I hope we can find time to explore the bird sanctuary,” she said to B.

“Why are you so excited to see flamingoes?”

“Because I’ve only seen them in zoos.”

“Or plastic ones in front yards,” B pointed out. “Paper plates, birthday hats.”

“All the more reason.” Anna turned to the woman waiting with them, whose niece seemed to have fallen asleep. “We don’t have flamingoes where we come from,” she said in Spanish.

“So elegant,” the woman said. “For me they are also exotic.”

“Mom, look, he’s here, too,” B said then, pointing. The drinker slumped against a wall, crying quietly, jacket draped open, watch cap askew. In the bar, the flashing red and purple had made him look haggard. In daylight, Anna saw he was maybe twenty-five, tops. She read the slogan on his t-shirt: Stop the Meltdown! Not a mushroom cloud—terror of Anna’s generation—the shirt’s image was a glacier wall above a lake. Anna felt she should say something, didn’t want to presume. She was still waffling when the young woman who had taken their entrance tickets came out and put a blanket over him. Whispered something. The man looked up—grateful? dazed?—then closed his eyes.

The shuttle arrived at last, another minibus, its museum decal starting to peel. B stood up. The other woman nudged her niece. “Last one,” she said, loud enough for a general announcement.

The man didn’t move. “Is he okay?” Anna wavered. “Should we. . . ?”

B shrugged and climbed onto the bus. “He gets it. He’ll deal.”

“But—”

“That lady inside knows he’s here.”

Next morning, the bus picked them up right on time, seven a.m., for the drive to the national park. They’d packed a lunch, ham and cheese sandwiches from the hotel kitchen, dried fruit they’d bought in Buenos Aires. They wore rain pants over their hiking pants, sunglasses, wool socks. Neither said much on the ride, watching the play of light out the window, snagging scraps of others’ conversation. An hour on the tour shuttle, a boat across Lago Rico to a simple pier. From there, they approached the glacier on a boardwalk through open woods, pausing to admire the lenga, trees like sycamore or poplar, light green shade and shadow. “A very special tree,” the guide told them, a kind of Patagonian beech, or maybe she said oak—Anna struggled to retain tree names in any language, had looked up maple (arce) more times than she could count. The trunks were dark, then silver-gray. B bounced beside Anna, picking up leaves, pointing out clouds, listening for birds.

They emerged onto a gravelly, muddy beach. Anna looked up at the glacier, white and gleaming, sparkle blinding. A sheer border at the end of the lake. No intertidal zone, no fuzzy boundary: water and then a wall of ice. Lucía, their guide, gathered her flock. Anna and B were at the back. They went around the circle, first name, hometown. Two French couples, a handful of Germans, a woman from Greece. With B in mind, Anna had selected the English-language tour, forgetting it would be a second or third option for many, a language of convenience.

Lucía explained the route, the process. Trek sounded wild, unbounded, but they would be coached and monitored through every inch of contact with the ice. “Afterward, we share a toast,” Lucía promised, “whisky with local ice.” She glanced at B, amended, “Just a sip.” Keep the tourists tipsy, Anna thought, make it a party. She tried to recall what she’d learned at the museum, the facts about melting, density, speed. Not the accelerating rush toward disaster. Remembering that was why they’d come, but also what she was trying to forget.

They crossed a well-pounded band of snow to a low, three-sided shed. The walls were hung with crampons, two or three pair to a hook. Each trekker chose a pair, strapped the eight-pointed frames onto their boots. It took time to get everyone outfitted; broken buckles, stiff clasps, mistaken sizes. Attentive to her youngest charge, Lucía gave B’s webbing straps an extra tug.

Single file, they stepped onto the ice. Constant cries of Careful! (some unspoken, swallowed, silent). Anna felt an instant’s suspension above the surface before the crampons dug in. She pushed a foot forward—it did not slip. A quiet crunch, a catch and grab as the points bit. Even under controlled conditions, the ice was dizzyingly varied, blue and white and speckled, bumpy or slick, textured with unexpected swirls. Ice that had been snow, accumulated and opaque, lustrous. Clear sheets, some bubbled, others rayed with angled subdivisions, over blue liquid (turquoise blue, swimming pool blue)—distinct from the blue of the sky with its pale skiffs of cloud. Lucía pointed out melt patterns, dirt on the snow, divots surrounding the smallest speck. The glacier rose up toward snow-capped peaks bursting with photo-spread exaggeration. The trail didn’t feel crowded. Cheerful, friendly—they’d all come for the same thing—people took turns, moving slowly, wanting to photograph every bit. How could all this be gone in less than twenty years? That it was likely true made it no less impossible.

Anna knelt on the lip of ancient ice, felt the cold through the layers covering her knees, welcomed the acute sensation in the midst of visual excess. Color and glittering light, sharp cold in her throat, breath held, expelled. Overload. Underload. Winter sunshine, bright but not warm. Voices weaving and overlapping and getting lost in the wind and the huge silent quiet of sun and cold. She tried to absorb and savor, and at the same time record every instant—for posterity, for comfort, for proof the shrinking glacier had been real. Proof she and B had been there, been there together.

“Even the air tastes cold,” B said, tongue waggling into the wind.

“What does cold taste like?” Anna asked.

“Sort of . . . plain.” B shrugged. “Cold tastes like nothing, a nothing you can taste.”

And then it was over. Up and over a gentle rise, a steep incline, side-stepping down a chute like real mountaineers, and there were Lucía’s colleagues pouring glacier-cooled whiskey, congratulating the trekkers on a goal achieved.

B picked up a thin tile of ice and made as if to take a bite, front teeth resting against the transparent sheet. “I thought it would be longer. Wilder,” B said. “I mean, it’s amazing . . .”

Anna nodded. “I know.” She felt the memory receding and blurring and expanding all at once. How could it be enough to visit one time, one hour? We did visit the glaciers, she might tell a friend. It was amazing. And yet.

After dark, after dinner, ready for bed at their storybook cottage, Anna scrolled through her pictures. She had resolved to delete a few each day of the trip; even so, there were hundreds just from the trek. Ice like panes of glass. Specks, pocks, dimpled curves and angles. Ice that felt wild, shifting, untamed, though they had not roamed free across it.

Anna smiled at a close-up of B from the bar, broad grin circled by fluffy fake fur. She regretted not stealing one of those gloves. She might have started her own home ice museum with the souvenir glove as star attraction. Better yet, a poncho she might have carried as a shield against the mustard burn of regret. She hadn’t done enough, hadn’t known what to do. Which mostly summed up parenthood too—endless loss, change, gratitude, hope. A front row seat for the (not so) slow motion end of the world.

Anna tapped the video she’d recorded. “People are trying to sleep!” B called from upstairs. For once, Anna turned up the volume rather than snapping to attention. This frozen moment. Anna and B, dressed in silver, shining in the dark, twirling and laughing, singing along. B’s lips were moving, Anna was sure of it.

“That was so much fun,” B said then, hopping off the lowest step.

“Aaah!” Anna gasped. She had been fully absorbed.

“Sorry!” B joined Anna on the bed. “Didn’t mean to startle you.”

Anna tried to laugh it off. “I guess I was taken with my own cinematic skills.”

B reached for the phone. “Let me see.”

Anna tilted the screen so they could watch together. Her lacerating certainty that she had failed her child, would continue to fail, slipped sideways, broke open, just enough for her to hum along. “It was fun, wasn’t it?”

“So fun!” B snuggled closer, hair still smelling of the cold. “At least we saw ice for real,” B whispered.

“We did,” Anna said, voice catching. She tapped play one more time. On the tiny screen, they might dance and dance. Anna will never be able to do the math.

Amalia Gladhart is a writer and translator in Oregon. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in The Common, Portland Review, Cordella Magazine, Saranac Review and Eleven, Eleven, among other publications. She is a recipient of a translation grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, and a winner of the Queen Sofía Spanish Institute Translation prize for her translation of Angélica Gorodischer’s Jaguars’ Tomb.