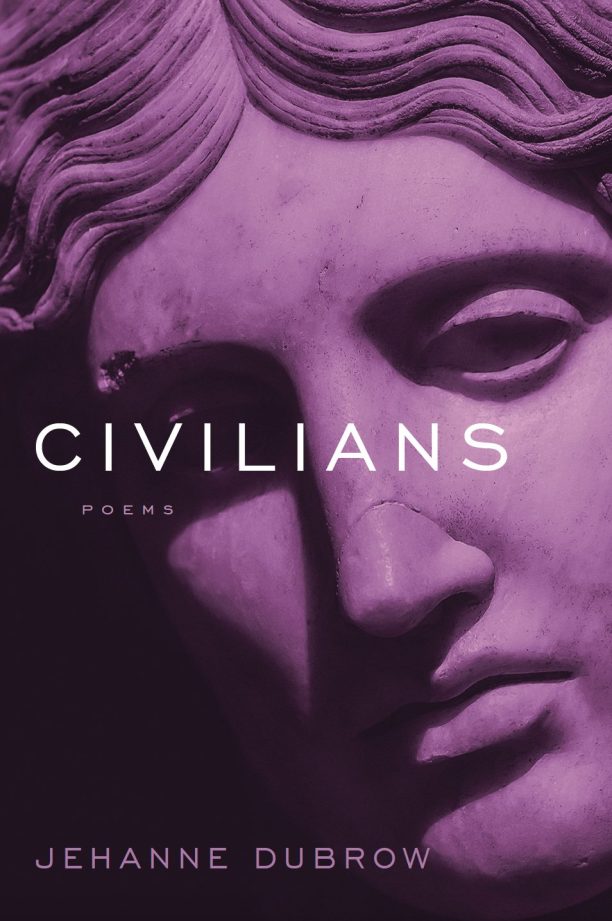

JEHANNE DUBROW is the author of ten poetry collections and three books of creative nonfiction. After twenty years in the U.S. Navy, her husband recently completed his tenure as an officer, and this transformation led Jehanne to write Civilians, the final book in her military spouse trilogy, a sequence that began with the publication of Stateside in 2010 and continued with Dots & Dashes in 2017.

Novelist, poet, and Marine veteran spouse VICTORIA KELLY sat down with Jehanne to discuss Civilians, which confronts pressing questions about marriage, transitions, love, and war. Though they have known each other virtually for over a decade—as two members of the very small literary community of military spouse writers—this was the first time they connected face-to-face.

Victoria Kelly (VK): Your new book Civilians is the final volume in your trilogy about the experience of being a modern military spouse. Can you give us some background on your family’s experience with the military?

Jehanne Dubrow (JD): I’m the daughter of two U.S. Foreign Service Officers. I grew up in American embassies overseas. To be a diplomat is to be a civil servant; so, I thought I understood—through my parents’ work—what it means to serve. I was familiar with the landscape of military bases because those were the sites where we could feel most American during our postings abroad. For instance, when we lived in Communist Poland in the 1980s, we would drive to West Berlin every few months for doctor’s appointments and to buy groceries and other goods. Those trips were a reprieve from the grayness and deprivations of Warsaw. I always looked forward to visiting the Post Exchange (PX) and commissary in West Berlin, seeing all those aisles of soda, toothpaste, and toilet paper. We would go to Baskin Robbins for a scoop of mint chocolate chip. I thought these childhood contacts with military life were insights into the culture, but only in marriage did I come to understand military service.

My husband and I were college sweethearts. After we graduated, we broke up for eight years. And then, by the time we reunited, he was an officer in the Navy, and I was an aspiring academic. This meant that we spent the first fifteen years of our marriage largely apart. First, I was completing my doctoral studies in Lincoln, Nebraska, while he was in Norfolk, Virginia. And then I began a tenure-track position at a small liberal arts college in Maryland, while he was sometimes in Virginia and sometimes on a cruiser or an aircraft carrier. Eventually, I moved to Texas. And after his 20 years in the Navy ended, he moved here to Denton. That was the first time we lived together in a significant and extended way.

VK: I’ve always wanted to ask you—how did you make that work?

JD: It certainly wasn’t easy! I think that’s why in Civilians, as well as in the two earlier books in the trilogy, Stateside and Dots & Dashes, distance is an even more palpable presence than the threat of war. For us, facing so many months and years apart was the greatest strain on our marriage. Because Jeremy wasn’t serving in a combat role but was a Surface Warfare Officer (what’s known as a SWO) onboard a Navy vessel, I worried less frequently about his physical safety than I did about the endless cycles of absence, those accelerated battle rhythms, which defined much of our marriage. That’s not to say, of course, that his service didn’t scare me. It did. I worried constantly about his physical safety.

VK: In one poem, you write “we fold these endings // with neat and pointed corners.” I love the irony of that moment because that’s not, of course, how the transition into civilian life happens.

JD: Oh, exactly. Becoming a civilian after twenty years of service is anything but “neat.” Every time I finished one of these books, I thought I was done with the subject of military marriages. With Stateside and Dots & Dashes, I told myself, oh, now I can move on to something else. But when it was clear that Jeremy was going to retire, I realized that we had both changed a great deal. I wondered: had we altered in complementary and parallel ways? I thought about how I might narrate my husband’s transformation from an active-duty service member into a civilian. But also (as you know) one of the labels that we are given as spouses is “dependent,” an identity with which I often struggled. I’ve never thought of myself as dependent on anyone. Still, I knew leaving that label behind would be its own kind of loss.

This led me to think about transformation in general, which eventually allowed me to return to Ovid’s Metamorphoses as the essential source text for Civilians. It struck me that becoming a civilian—when you’ve spent two decades in uniform—is as radical and unsettling a transformation as a mythical girl changing into a laurel tree.

I worried less frequently about his physical safety than I did about the endless cycles of absence, those accelerated battle rhythms, which defined much of our marriage.”

VK: Could you talk about your choice to have multiple poems in the book titled “Civilian?”

JD: The book is called Civilians because, after retirement, we both assumed the same label. He was no longer an officer. And I stopped being a dependent. When I started trying to make sense of what a civilian is, my first step was to look up the word’s definition (as poets often do!). A civilian is defined by negation. A civilian is somebody who is not a combatant. Immediately, I wondered about the consequences of taking on an identity defined by what one isn’t. In response to this question, I wrote quite a few poems titled “Civilian,” far more than are in the collection. Each one is an effort to get at some essential quality of being a civilian, thinking like a civilian, and processing the world in the manner of a civilian.

VK: You do a beautiful job of weaving together different landscapes in the book. How do all these specific places you evoke relate to the themes of home, transition, and love?

JD: Throughout the trilogy, place plays an important role, especially because the physical location of the speaker is so often fixed, while the husband has agency and movement, traveling across countries and time zones. For Civilians, I recognized that I needed to address the landscape of Texas as a strange kind of literary foil to all that open water, which previously filled so many of my military spouse poems. Stateside is such a watery book, and even Dots & Dashes is mostly set along coastlines. Now we live in North Texas, hours away from the nearest shore. And yet, the massive amounts of open space—all the prairie, marsh, and plains that we have here—started to feel like another kind of vast water, another great expanse of distance and isolation.

The landscape became a character in Civilians. Early in the book, I write about my husband’s bachelor pad in Norfolk, Virginia. He had rented out the house to various terrible tenants during different deployments, and they absolutely destroyed it. One tenant left the home so filthy and roach-ridden that Jeremy basically needed to power wash every surface. In the poem, this squalid house turns into a symbol of how we were still failing to connect or to be present for one another. In the poem, I write that “The metaphor was too easy— / in his absence he neglected home. / I didn’t help with the cleanup.”

VK: In several poems, you write about American attitudes towards the military. For instance, in “Flight 2270,” you talk about being on an airplane when the captain asks that the passengers acknowledge the service members who are on board by clapping for them. The response on the plane is half-hearted. What was your inspiration for this poem? And how do you feel war is perceived in general today by Americans?

JD: That little moment on the airplane happened on a flight that I took to a writer’s conference in Tampa. The whole time I was in Florida, I kept thinking about the applause. And on the flight back, I wrote the poem because I was trying to figure out what had bothered me about the clapping. The applause struck me as complacent and maybe a little self-satisfied, as if people were proud of themselves for expressing gratitude. I kept trying to make sense of my response. Why did this moment irritate me? My poems frequently begin with questions that I’m trying to answer for myself.

I suspect I was particularly alert to the possibility of a poem because I was going to a writer’s conference, a space where it can feel especially uneasy to be a military spouse. In my experience, people don’t know what to do with us in those kinds of spaces. Sometimes they think that our feelings about global conflict and American foreign policy must be less complicated than theirs, less sophisticated somehow.

And, to answer your second question, yes, I think American perspectives of war have shifted a lot since I first began writing about the military spouse experience in 2005. Twenty years ago, it seemed like civilians—even people who weren’t directly affected by military service—were more interested in making a distinction between the soldier and the government that sends the soldier off to fight. I think many people remembered the divisive rhetoric of the Vietnam War and wanted to learn how to communicate about war with greater nuance and care. I worry that, in the age of social media, much of that nuance has disappeared again, especially in academic circles, where I spend most of my time. I’m concerned that we’ve returned to a moment in which soldiers are once more called “baby killers” and that these forever wars have led some civilians to feel contempt toward military service. This means that the military spouse also becomes a figure to be implicated, criticized for loving someone who wears a uniform and who is part of the machinery of the state.

That’s part of what makes it difficult to write these poems. Publishing this work might be an even greater challenge. Over the past twenty years, there have been times when an editor at a literary journal has told me: we don’t publish military propaganda. I’ve never written a pro-war poem. I write about what it’s like to be part of a marriage in which distance, fear, and the presence of war, shadow the couple’s every effort to preserve intimacy and closeness. Occasionally, in sending out these poems to journals, it has felt like readers were bringing their own preconceptions about military families to the page, instead of seeing the poems for what they are: an effort to engage with the inevitable distances and mysteries we experience with those we love most.

Marriages are sites of intimacy where the tensions are enacted through the small details of daily life.”

VK: What is your response to the assumption that poetry should have a social or political message?

JD: I think that most poems contain such messages, but I think the question is: how subtle is that presence? How directly (or obliquely) are the social and the political enacted in the text? For instance, I read my books as being clearly anti-war. But I think some readers might wish for a more strident approach.

I see my books as engaged in a feminist project; these collections assert the right for a woman to articulate her perspective which, as you know, hasn’t always been encouraged in American military culture. Even the act of saying, every military marriage is placed under tremendous strain and pressure, is a political gesture. But I’m also interested in writing poems that think broadly about what we can expect a marriage to endure. War. Distance. The looming possibility of trauma. And how do the two figures in this relationship respond to such threats? This is why writers like Homer, Sappho, Ovid, and Sophocles—to name a few—have been so important to me throughout my career. The Classics speak to our current political concerns, but they look past us as well; they are both of the moment and beyond it.

I hope too, in the way of Wilfred Owen or Siegfried Sassoon, I can speak to the specificity of our current conflicts while also addressing larger questions about war in general.

In Civilians, there’s a poem about Afghanistan titled “Domestic Policy.” It’s about America’s disastrous withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021. The poem is a critique of American foreign policy. But it’s also a narrative about marriage. A couple is having a terrible argument, so bad that they’re considering divorce. I write, “Marriage is not / two ideologies fighting at a table, / while the soup goes cold / on the spoon.” And I believe that. Marriages are sites of intimacy where the tensions are enacted through the small details of daily life.

VK: That’s perfectly phrased. If there is one important social issue you bring up very directly in the book, it’s veteran suicide.

JD: I first began to think about veteran suicide when I was living in the DC area and leading workshops for active duty service members, veterans, and their families. I went to a conference at Walter Reed on the use of the arts as a tool for healing. This was probably about fifteen years ago. At the time, we were in the middle of a public health crisis, in terms of the number of veterans who were dying every day by suicide. It was obvious that military medicine needed to look beyond the usual treatment methods to other therapies, including poetry workshops, art classes, and music lessons. And even as recently as last year, it’s estimated that more than seventeen veterans die by suicide daily.

Then, shortly after my husband retired, a friend of his died by suicide. And I remember the day he received the news. I watched him standing on the back porch in the rain. And that’s how this tiny little poem in Civilians came to be. “My Husband Learns of Another Sailor’s Suicide” is the shortest poem in the book. It probably challenged me more than any other piece that I wrote in the collection. My husband had said to me, this isn’t your story to tell. And I knew he was right. So, the poem is very careful; it simply shows the speaker watching her husband through the window as he learns of the death. The only way that a reader understands what’s happening is through the title, which is doing a tremendous amount of narrative work. I remember watching my husband that day through the frame of the glass and thinking, something terrible has happened. I could see it in the stillness of his body.

VK: I have to ask you the inevitable question: What’s next for you now that this trilogy is complete? Are you working on something new?

JD: I’m always working on two or three books at a time. It’s how I prevent myself from becoming bored with my own voice. My first craft book, The Wounded Line: A Guide to Writing Poems of Trauma, will be published by University of New Mexico Press in the fall of 2025. I’ve spent the last twenty years writing, teaching, and studying how we represent trauma on the page. This book came out of what I saw in the classroom; my students wanted to write about the traumatic but struggled to identify craft-based strategies that would allow them to engage with such material in artful, ethical ways. I started working on The Wounded Line because I wanted to provide very usable skills to poets at all stages of their development, practical techniques that would allow them to approach both large-scale, historical traumas, such as genocide or enslavement, but also the smaller, personal traumas that we experience as individuals.

I’m also working on a new book of poems called The Brief Temple Taken Down, which is about the relationship between the health of the body and the health of the body politic. And I also just finished writing a book-length essay called Frivolity: A Defense, for “No Limits,” a philosophical series that Columbia University Press publishes. Frivolity explores frivolous pursuits, things, and people, attempting to understand why frivolity has been so derided and what might be valuable about the frivolous. It was such a pleasurable book to write because it allowed me to spend time with the frivolities that I love, such as perfume and fashion. I hope Frivolity will resonate with readers. We need a little lightness in dark times, after all.

Jehanne Dubrow is the author of three books of nonfiction and ten poetry collections, including most recently Civilians. A craft book, The Wounded Line: A Guide to Writing Poems of Trauma, will be published by University of New Mexico Press in 2025. Her writing has appeared previously in The Common as well as in New England Review, Southern Review, and Ploughshares. She is a Professor of Creative Writing at the University of North Texas.

Victoria Kelly is the author of three books: a short story collection, Homefront, a novel, Mrs. Houdini, and a poetry collection, When the Men Go Off the War. She is a veteran spouse and a producer of the upcoming documentary Atomic Veterans (atomicveteransfilm.com).