By SCOTT GEIGER

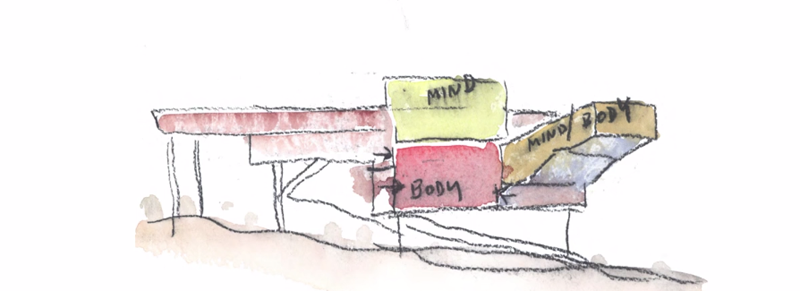

“We have the mind, body, and the mind/body all organizing this building,” offers architect Chris McVoy, metaphorically describing the Campbell Sports Center that opened this fall at Columbia University. The building is the outward expression of an athlete’s inner journey. In a short film, McVoy and his partner and mentor, Steven Holl, discuss their design intentions and the character of experience they’ve created.

The film captures the strong sense of place at Manhattan’s northern tip. The Campbell lives on Columbia’s athletic campus at Broadway and 218th Street. A couple blocks west is Spuyten Duyvil, the tidal whirlpool that shunts the Harlem River from the Hudson. Nearby bridges carrying route 9A and the 1 Train leap the distance to the Bronx. Industrial buildings mix up a thin but established residential neighborhood. Steven Holl mimics these surroundings in his design through the Campbell’s shining angles in steel, glass, and concrete. The architecture is thrown above the city in a circuit, a rectilinear lasso swung beside the subway tracks. Flyway staircases drop back to the sidewalk, to the sports field.

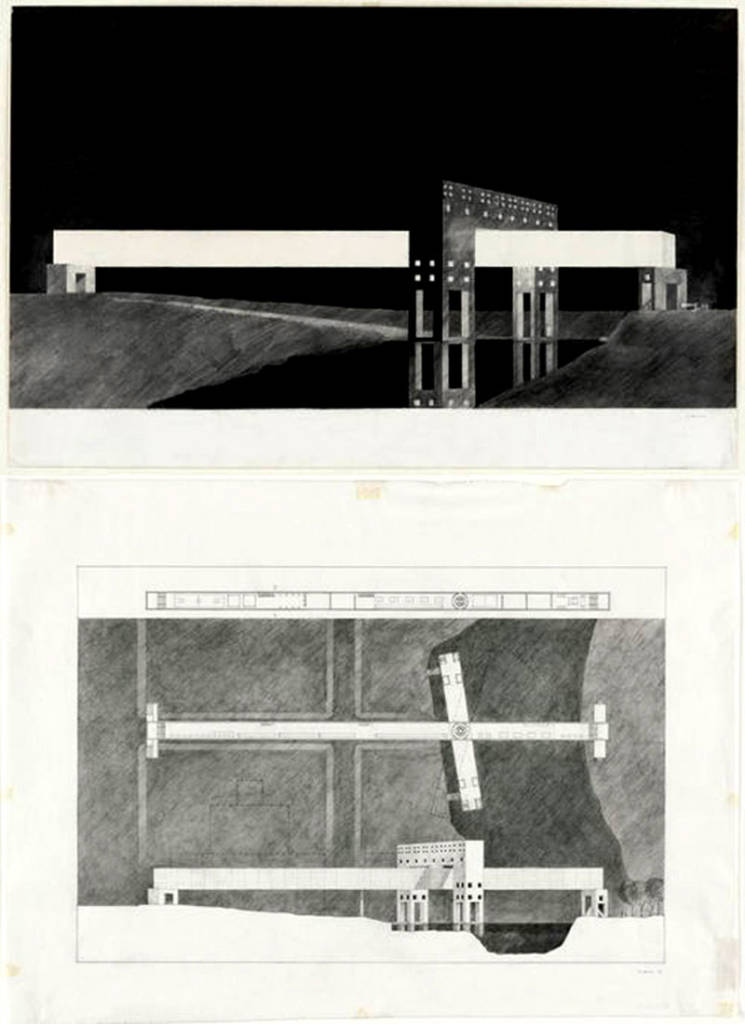

News of the Campbell Center reminded me of Steven Holl’s 1977 proposal for the Gymnasium Bridge, a submission for a competition held by the Bronx’s Wave Hill Center. The subject of the competition was a new pedestrian bridge allowing residents from the ailing South Bronx access to parklands on Randall’s Island.

The central drawing of the scheme represents the project not as bridge but as a pair of horizontal buildings radiant against a plutonian dark. From the Gymnasium Bridge beams a hot intensity, perhaps associated with the physical activity Holl proposes inside—boxing, weightlifting, basketball, football, even ice skating and rowing. Holl’s text for the competition reads, “Along the bridge, community members participate in competitive sports and physical activities organized according to a normal work day with wages on a payroll provided by a branch of the Urban Jobs Corps or a reconstituted WPA etc. While earning enough money to become economically stable, community members gain physical and moral strength and develop a sense of community spirit.” Holl’s proposal creates a world around this passage.

Gymnasium Bridge was of its time: a postmodern riff on New York City bridges fashioned as Renaissance Italian structures like Florence’s Ponte Vecchio. Contemporary Holl works in China show greater family resemblance to Campbell Sports in their form, their materials. The Sifang Art Museum in Nanjing, for sure; the Vanke Center too, though at a grander scale. Yet the Campbell Sports’ athletic program and uptown New York City location so strongly suggest the Gymnasium Bridge. The 1977 proposal won a P/A Award from Progressive Architecture magazine the following year, and Holl’s career was up and running almost. He would work from apartments in TriBeCa and Chelsea for a few years yet—as myth has it—bathing at the YMCA, sleeping on a plywood board.

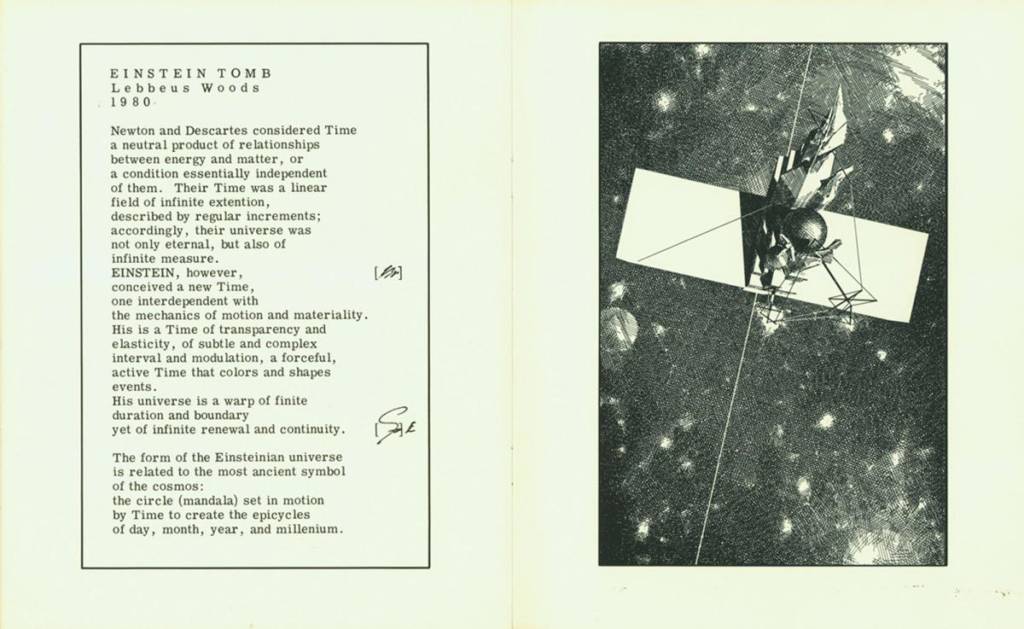

Almost as cool as the Gymnasium Bridge itself is the vehicle made to broadcast it to the world. In December 1977, Holl and San Francisco bookseller William Stout issued a ‘zine-style publication collecting the drawings, model photographs, and texts from the Gymnasium Bridge proposal. That booklet became the inaugural issue of Pamphlet Architecture, an annual series that has proved over decades the richness of architectural ideas explored purely in drawings and writings. From the first page of Holl’s pamphlet, on which he chisels an epigraph from Rimbaud’s poem “The Bridges,” the series has carried a literary air. Pamphlet Architecture is about the languages of architecture, about visual experimentation used to evoke new and unexpected experiences for readers.

Iraqi-born British architect Zaha Hadid is likely the most widely known architect to debut their ideas in the series (#8 Planetary Architecture). A number of influential academics and theoreticians like Neil Denari, Lewis, Tsurumaki, Lewis, and Smout Allen also have influential editions. Some pamphlets lean toward the technical, others toward lyric philosophy. Of these, easily the most valuable are Pamphlet Architectures #6: Einstein’s Tomb and #15: War and Architecture, both by the late Lebbeus Woods.

For description of Woods’ work, I defer to Geoff Manaugh’s obituary for him from one year ago: “When I say that Lebbeus Woods and James Joyce and William Blake and so on all belong on the same list, I mean it: because architecture is poetry is literature is myth.”

I’m excited to say that the very first architectural proposal to appear in print in The Common is a collaboration between two authors of recent Pamphlet Architectureeditions: Lateral Office (#30: Coupling) of Toronto, Canada, and Luis Callejas(#33: Islands and Atolls), of Medellin, Colombia. The Common 06 includes their urban master plan for a city center in the Faroe Islands.

Klaksvík is part ancient fishing village, part twenty-first century Scandinavian city. Lateral Office and Callejas have proposed a suite of small moves to clarify and reorganize the community. Their scheme is stylishly drawn and intellectually intriguing, but its modesty is also notable: A network of public spaces and streets defines their City Center, not an iconic, singular building. “Peaks and Valleys” mounts an appropriate vision of tiny Klaksvík’s place in the world and a good interpretation its relationship to nature.

Architecture means something very different in “Peaks and Valleys” than in the Gymnasium Bridge of 1977. Holl and Lateral Office/Callejas make very different appeals to realism to insinuate their design in the viewer’s imagination. It’s in this effort that architecture can be said to achieve a status like literature. That neither scheme will be actualized is no matter. We are invited to weigh their design against our hearts, and through them understand ourselves and the world. Perhaps the power Geoff Manaugh saw in Lebbeus Woods is that his work warps beyond the question of selling or insinuation through to achieve realism loyal only to itself.

I hope you’ll take a moment with “Peaks and Valleys: Klaksvík City Center” by Lateral Office and Luis Callejas in issue 06! I’d be glad to hear your feedback too as well as your thoughts on Pamphlet Architecture #30: Coupling and/or Pamphlet Architecture #33: Islands and Atolls.

Scott Geiger is the Architecture Editor for The Common. His fiction has earned a Pushcart Prize and a 2012 New York Foundation for the Arts Fellowship.