Rosa Castellano (left) and Raychelle Heath (right)

RAYCHELLE HEATH (RH): Rosa, it is so lovely to meet you, and All is The Telling is such a beautiful read. The book is structurally interesting, and it’s inspiring on many different levels. The stories of different girls and women drew me in immediately. But, I want to start with the title. You’re telling a layered story here, and I’m curious how you arrived at the title. How does the title poem place the characters in the story arc of the book?

ROSA CASTELLANO (RC): I love this question! I hope that the collection’s title and the poem prepare readers for all of the telling that takes place in the book, which is largely concerned with telling stories and telling our truths, especially the stories we carry in our bodies. I subscribe to this idea of the layered self, like a series of paper dolls we can tug open to find a line of selves connecting who we are now, back to all the selves we’ve been, those previous identities that we hold. That’s how I’m hoping the poems in this collection work, linked together with various kinds of repeating patterns, working to tell the interconnected stories of a self. It’s a complicated thing, most days, to be an alive person.

RH: Yes. And you mentioned in your author’s note that those girl poems were inspired by Ntozake Shange’s “for colored girls….” You have quite a few references to Black women writers in this book. You referenced another one of my faves, June Jordan. We also get a reference to Toni Morrison and Alice Walker, and I think it’s beautiful when we can call in our literary ancestors to act as a foundation for the work that we’re doing. I’m wondering if you can speak on how those voices were at play as you were bringing this book together.

RC: [Laughs] I’m not young, so many voices have influenced me. When I encountered Shange’s work in my high school library, I was blown away. I saw her poems give voice to the kinds of things I knew in my body to be true. Those women writers I encountered in my early years—Morrison, Lorde, Hooks, Walker—their work, and especially “for colored girls…,” it’s foundational, and their language and rhythms echo inside me and show up in my work in conscious and unconscious ways.

I did live in a trailer park in Florida (like my poem suggests), and there wasn’t a lot of art in my early life. We didn’t go to galleries or museums. I didn’t see staged plays or encounter poetry or live music. But in reading Ntozake Shange’s work, I was invited into art, not just literature, but art. And the way she invites readers to imagine a stage, a set, a group of women, is to see them.

That’s what I wanted from my poem/play. I wanted for my readers an embodied experience that they could generate themselves. Because the invitation with a play, rather than with a poem, is to picture it. To see a stage, the two sisters, and to let it be up to each reader to put on this play, see these women, their bodies in motion on a stage. And that’s different from the experience of silently reading a poem and wondering if the speaker is the author or experiencing whatever images come up as you read.

With my poem/play, the invitation is to imagine, and the seeds for all kinds of details are in the play. But what blooms on the stage will depend on the “mind” staging of the reader, and I love the possibilities inherent in this kind of collaboration.

RH: And the play stands out because it is a bit of a structural departure from other things that are happening in the book. The book wants to talk about race, and it wants to talk about the South, but the play is set in a different era and has echoes of Nella Larsen’s Passing. I’m curious, in a book that’s so clearly rooted in the present day and has poems that talk about the internet and things that are happening now, why did you want to include this moment that pushes us back in history?

RC: Some of us carry stories in our bodies because of intergenerational trauma. We live in this now with parts connected to our collective past as African Americans; inherited traits handed down to us that might not belong to this now. And so I wanted to offer up a story in this book, poems that look backwards in a way that could inform our now.

I’m part of a Black ancestral lineage, and I have four children. Two are white-passing, and two are mysteriously or ambiguously brown. So, how do I help them situate themselves in this world? I think that’s a question, not just for light-skinned folks or people who are in a position to pass like one of the sisters in the poem/play, but for all of us in this country whose identities are tied to caste.

RH: How we think about passing now is very different from what it meant in that era. But we are still confronting how we create division and connection. The play plays with time, pulling us out of the linear and making the focus the sisters. What was your thinking around creating this kind of non-linear exchange between the sisters about how they’re moving in the world?

RC: Time doesn’t always operate in linear ways. Narratively, it’s a fun way to tell a story, and also from the point of view of a reader, it can be a great way to experience a narrative. Arranging poems in a non-linear sequence offers readers a chance to think about how we move in and out of our own stories and memories in non-linear ways.

Which brings me back to that image of a paper doll, which I think can kind of also work like an echo. Like maybe when you see someone you knew as a baby who is now a teenager, the ghost of that baby face, that previous self, is still sort of visible in their walk or smile. In my “Girl the Color of…” poems, some of those speakers are young and some are not, even though they are all called “girl.” And I don’t know how successful that is (laughs), but I want readers to feel the echo of time in their bodies if possible. And I don’t mean timelessness, but more of an embodied sense of time—I love the idea that maybe we can embody time enough to be present with ourselves or with a poem.

And not necessarily, consciously. I think there is something about a Black body’s relationship to time that is as inescapable as intergenerational trauma. You can not look at the violence that’s happening to Black bodies right now without thinking, something along the lines of again? We hold all these things in our bodies that often go unacknowledged, and it can add to our confusion.

RH: I think we’re moving past this idea of carrying bodies through time and moving into being present in body and present in space. And there are so many echoes within the book of how we are viewing Black bodies and how we connect intergenerationally. One of the poems that comes to mind is “A Doctor’s Comment on the Fitness of His Body,” where we don’t know what time we’re in. That poem is so impactful, especially in the way it very minimally describes the dismembering of a Black body in a very transactional way. Could you talk a little bit about that poem?

RC: This poem exists in the intersection of my last memories of being in a room with my brother, and the moment, for the medical personnel, he became a body. It was very difficult to talk about at the time, in part because the grief was so fresh, but also because my concerns were often met with celebratory remarks around the donation of his organs. I can appreciate this; my friend’s life was saved by a kidney transplant. But there are conversations we need to have around how we treat Black bodies, and I think this poem is trying to carry some of that weight.

I want readers to feel the echo of time in their bodies if possible. And I don’t mean timelessness, but more of an embodied sense of time—I love the idea that maybe we can embody time enough to be present with ourselves or with a poem.”

RH: I think it does. Especially since you don’t start with the organ donation; you start with the death. There are so many of those moments in this book where we’re kind of cruising along and thinking we’re having a “normal” experience, but then we’re reminded that things are different when you live in a Black body. Reading this book as a Black woman from the South, I was in it. But this book is going to be in the hands of many readers. I know that storytelling is a part of what is happening here, but we’re also having some real conversations about what it means to live in a Black body in the United States. And we’re in a time right now where a lot of people don’t want to have those conversations. What are you hoping the reader will take away from this book? But also, where do you feel like this book lives in that conversation that so many people don’t want to have?

RC: Many of us are constantly thinking about survival, and that’s one of this book’s primary concerns. How did we survive our lives so far? How do we continue to survive? And most importantly, how do we survive together? The world feels like it’s breaking. In each news cycle, there’s something catastrophic happening to someone’s family or livelihood, or home.

I know that I can’t effect policy change, or personally end the genocide in Gaza, I can’t even make the kids on my son’s soccer team be kinder to the one non-binary child on the team—but by writing these poems, I can hold space for folks as they attempt to process whatever they need to process. I believe poetry is a place that can offer healing and hope, and so, this book, while it’s just a book like all poetry books, is just waiting to be found and put to use.

Reading is not passive. Lives are changed every day by books. My life was changed for the better, multiple times, by books. I, like most writers, poured myself into this book and want only for folks to find it, to take it in and have whatever experience they are going to have with it. We bring our whole selves and all our experiences to the poems we read, and sometimes because of that, we fall in love or learn something or just feel seen. It’s a kind of chemistry—you plus me equals something more than we make on our own, and that’s true in life and in what happens when we read each other’s words. I hope that folks reading the book will have moments, and these moments don’t have that much to do with me, not really—I’m talking about the way poems can return us to ourselves. We need sweeping, humongous change across multiple sectors and systems, but most of us need healing for that to happen, and sometimes, it’s poems that show us the way.

“I believe poetry is a place that can offer healing and hope.”

RH: I feel like we see that in the way you ended the book. “& Let Me Hold” is all about coming back to yourself. Talk to me about that poem.

RC: “& Let Me Hold” is 100 percent intended to be a hug. One I’m giving to myself, one I’m offering to readers. Because when we mine our truths for meaning, what comes up in the stories we carry can surprise us. Some of us have stories that are painful and hard to hold. But more than one thing can be true—I’m glad that my brother’s organs were able to help somebody else, even though I can’t shake the feeling that maybe his doctors didn’t do everything that they could have to help him. I was sixteen, so I have a sixteen-year-old’s understanding of that moment. I’m grown now and know other things: hospitals don’t or can’t always provide the care that they should to certain people. How do we hold all of these things that we’re being given by our lives all of the time?

I think we do it in collaboration with the page. And so the page offered in that last poem in the line, “& let me hold / this space, this page / ready / for one last thing” is a space being held for all of us. I’m holding a blank page all the time for myself. That’s a truth that I choose to believe in: the blank page is a tool for our collective liberation. It can be how we keep going. I love that we can find each other on the page and heal each other, too. So, I invoke that again and again, for myself, because I need it. And while I do love a poem or a book that ends on a banger, this book didn’t want to end that way; it wanted to end with a hug.

The blank page is a tool for our collective liberation. It can be how we keep going.”

RH: [Laughs] That’s so real. We’ve been talking a lot about the content of the book, but I would be remiss if we didn’t talk about some of the forms as well. For example, your titles, some are first lines and they move into the poem, but some of them are unique and abundant. I’m curious about how you choose titles.

RC: I care quite a bit about how a poem is received by readers. Some poems need the space of a performance to capture their intent and offer it to a reader, and I think form can do some of the work to enhance the meaning or emotional goal of a poem. A column of tight lines can make you read faster. If you mess with punctuation, you can catch a reader up, slow them down. The form a poem exhibits on a page informs the experience of reading, so that instead of walking down a hill, readers are tumbling.

And that’s partially why I think so much about titles—I’m invested in trying to make the kinds of poems that folks can read and then walk away with something. I’m doing the work of writing for myself, but hopefully there’s an audience. And I want to give them as much access to the world of the poem as I can.

RH: I can tell the book is very lovingly put together, not just with the titles and how you’re using structure and punctuation, but even the sections. You’re giving us open space to lean into, but it is also an expectation of what’s to come. I want to talk a little bit about the artistic elements in the book. How did you come about those, and what do they mean to you?

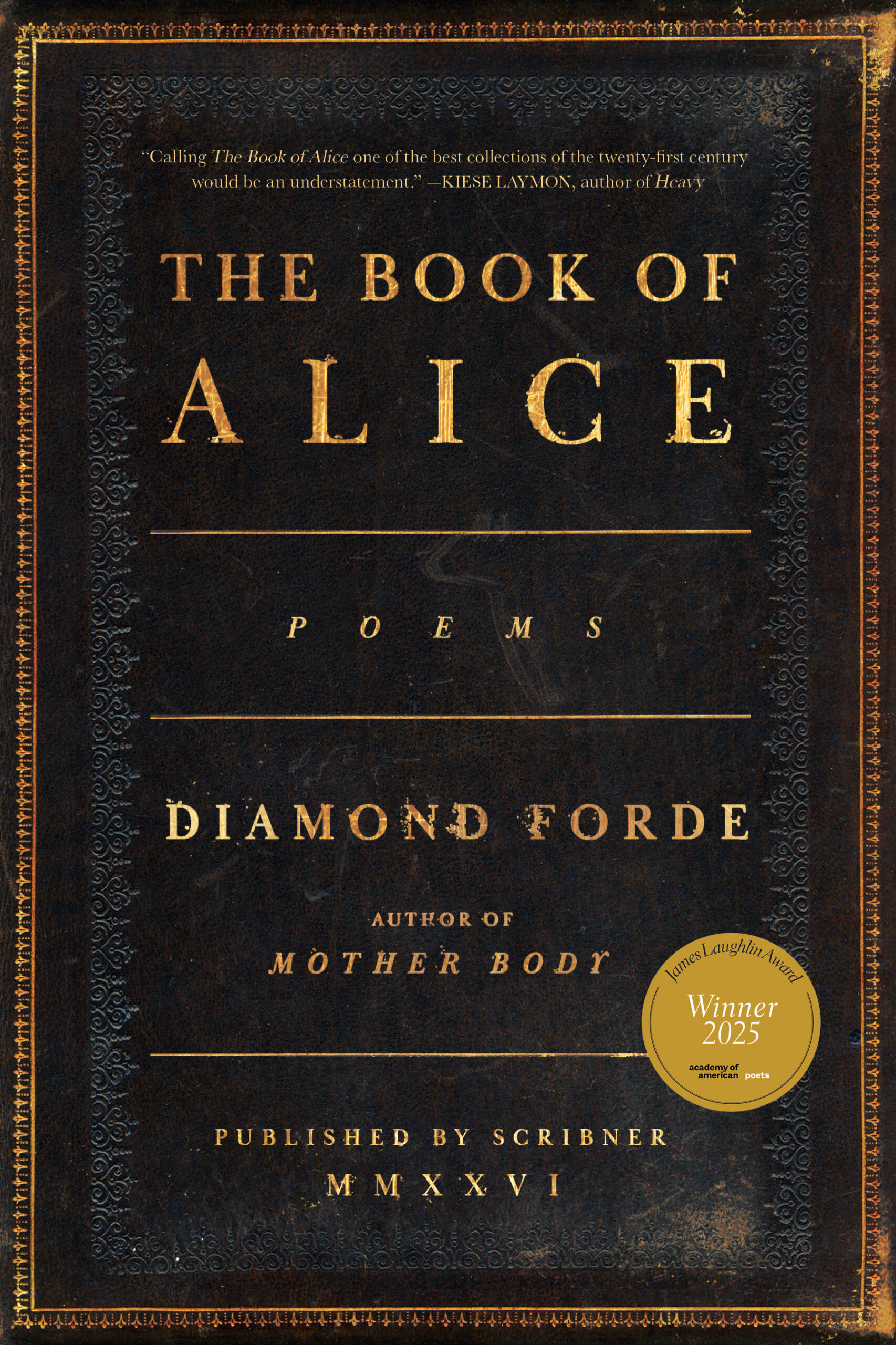

RC: So this gets into a little bit about bookmaking and what you can and can’t do artistically. The girl in the cover art is a representation of the girls in this book. And since the “A girl the color of…” series is an invitation to think about color and colorism, I wanted to use the image inside the book as well. I am a person who benefits from colorism and has privilege as a result of it, so I try to stay cognizant, but I couldn’t talk about Blackness without addressing colorism in some way. So, returning to Shange’s “for the colored girls…,” I wanted to try to parallel a little bit what she did with color and use the image from the cover as a physical manifestation of color as the girls fade from dark to light throughout the book. We thought that would be cool, but in the end, it was not possible financially or logistically with how book pages work. So there was a little bit of settling on how we could incorporate the image of the girl from the cover.

I also wanted more pages between the title and image so you could sit with her for a minute, because the first image, the all-black image on the white page, reads differently than the cover image. The girl on the cover image is a beautiful representation of southern Blackness. She is dark, velvet of the sky, and I hope she embodies Blackness and beauty. I like the idea that people could carry this girl with them throughout the reading, or not. I just want her to be seen. Ultimately, she’s a stand-in for the people we care about and can’t protect. We live in such crazy times, and people are getting hurt. People in our communities need us. And I don’t know what my book has to offer beyond connection and the fact that we are surviving, have survived, and will continue to survive, together.

Originally from Tampa, FL, Rosa Castellano is a poet and teacher living in Richmond, VA. A finalist for Cave Canem’s Starshine and Clay Fellowship, and co-founder of the RVA Poetry Fest, her poems can be found or are forthcoming from RHINO Poetry, Guernica, Nimrod, The Ninth Letter, and Poetry Northwest among others. She has an MFA from VCU and her debut poetry collection, All is the Telling, is available now from Diode Editions.

Raychelle Heath (she/her) is the co-director of the Unicorn Authors Club, where she also serves as a sanctuary coach and curriculum coordinator. Her work explores the multi-faceted experiences of Black women in the world. She has been published in various places, including Travel Noire, Fourth Wave, Feelszine, Yellow Arrow Journal, The Brazen Collective, and Community Building Art Works. When she is not writing, she is engaging with the wellness community as a certified Kripalu Yoga, Yoga Nidra, and Mind Body Meditation instructor.