By TANYA COKE

I.

Scrawny was my first thought. I’d babysat enough by then to place his age at just shy of a year. As my father handed him to me, the baby arched his back in protest, his chicken butt threatening to escape his diaper completely. I could tell that a man had fastened it, because the tape on the sides was all askew.

“Come, say hello to your brother,” Daddy said, smiling.

What could I do? I took the baby. He mewled and reached for my father, big brown baby eyes beseeching the man to save him from a stranger. I bounced the boy miserably on my knee.

“It’s important you know him.”

No, I thought, it’s important to you that he know me.

By that point, I didn’t much care what my father wanted. He’d told each of us, my sisters and me, about our brother a few weeks before in separate tête-à-têtes. As if this baby had materialized out of nowhere, through virgin birth. I didn’t bother to ask about the mother—it wasn’t my mother, and that was all I needed to know. I cut straight to the chase.

“Are you and Mummy getting a divorce?”

“No. Your mother and I love each other very much. We’re not getting a divorce.”

My mother’s version, naturally, was somewhat different. Her eyes flashed as she looked up from the carrot she was scraping, violently, in the sink. “Let me tell you something, girl. Men. Are. Dogs. Learn that from now.”

I asked who the mother was.

“He didn’t tell you?”

“No.”

She kissed her teeth long and sour, Jamaican-style. “That white woman from Athens. David Baird’s wife.”

I knew by then that my father had women on the side. He was a West Indian man, after all, exceptionally handsome and charismatic, with a raucous laugh that sailed high above whatever other foolishness might be at hand. He was an architect, not an actor, but he lit up a crowd like he was on stage. When John Braithwaite was in the room, his Jamaican friends cried “Rawtid!” a little louder, and puffed their chests a little higher. And the women. I could see their eyes following him across the room. The one named Elsa who ran the ballet school in Kingston when we were little, before we immigrated to the States. She wore tight white dresses and laughed as she touched the back of my father’s neck lightly. He elicited the curiosity of my white friends’ mothers, the ones from Columbus School for Girls, who would invite him to join them and their husbands for a drink around the pool after he dropped me off for sleepovers at their East Side mansions. When they drove me home the next morning, the moms would tell me how interesting my parents were, when I knew all the time they were really talking about my father. Only the most confident of my friends’ fathers could withstand his radiance long enough to become his friend.

But it didn’t matter if my rich schoolmates’ parents liked him or not, because Daddy had plenty of friends: a random collection of ragtag artists, musicians, and politicians from the length and breadth of Columbus, Ohio, a city so average that it had become test-product capital of the nation. Set down in a milquetoasty sort of place, my father gravitated to the extremes. Over lunches downtown, he hustled design contracts from Republican businessmen; in the evenings, he slapped palms with black aldermen and sanitation workers in East Side jazz clubs, where he would sometimes let me tag along. But it was the artists he really loved. He adored our elementary school music teacher, Mrs. Burns, a cheerful white lady who taught us Appalachian folk songs on a dulcimer but who in real life (according to my father) was passionate about Thelonious Monk. He loved his friends Max and Celeste, an interracial couple who made sculpture from found objects long before that was a thing. And his jewelry-making hippie friends, David and Roberta Baird.

I didn’t see the Bairds much growing up, because they lived two hours south of us in Athens, near the border with West Virginia. But we’d see them at least once a year at the Columbus arts and crafts festival. David and Roberta would be there for three days, selling earrings, necklaces, and rings they had fashioned from brass and natural stones in their studio. Roberta was quiet and slight, with light-colored hair that looked as if she’d cut it herself without the benefit of a mirror. She always seemed to me to be fully absorbed by whatever backdrop she happened to be standing against. David was another matter—he was bearded and well-built, with sapphire eyes so arresting they made you square your shoulders. He carried himself modestly, but with a quiet confidence, and was always very kind to me.

The two of them always made me a little uncomfortable, though. Growing up, I had assumed all poor white people to despise black people indiscriminately; my sisters and I knew instinctively to keep away from the neighborhood where many of them lived, west of downtown. I never once heard my parents use the term “white trash” or say a harsh word against people on that side of town, but I did remember how mean the white kids with dirty faces were to us in our old neighborhood when we first moved to Ohio from Jamaica.

Given these preconceptions, I had trouble digesting what my mother had told me, about the mother of my half-brother. I confronted my father about his infidelity, the evidence still on my lap, crying more loudly now.

“Roberta Baird, Daddy? As in Dave and Roberta?” I’d figured it was one of his high-class black lady friends. Maybe that stewardess who kept finding reasons to visit us on her trips to the States from Jamaica. But Roberta? She didn’t seem like the kind of woman my father would have noticed. I’d always assumed that David, with whom he talked art and politics, was the draw of the friendship.

“And are Dave and Roberta getting divorced over this?”

“No, no. Dave is raising Shawn as his own son. And I go to visit when I can.”

I didn’t say anything in response. I was furious, and too busy trying to compute the scenario. My black father had impregnated the white wife of his good friend—also white. Said friend had not cut off Daddy’s balls, but was instead raising the child as his own. In other words: white couple, pregnant with their first child, give birth to a black baby, whom they are raising in western Appalachia? I wondered for a minute if that was the kind of white community that lynches black men. Then I remembered. Dave and Roberta weren’t that kind of white people. They were counterculture white folks. I recalled my father telling me that they were part of an artist community deep in the hills of southeastern Ohio, where they’d built a house with their own hands.

Daddy was most definitely not handy that way. He was a designer, not an engineer or builder, prone to breaking our Christmas toys during assembly. And so when he bought fifty acres of richly soiled land in the foothills of the Blue Mountains, he invited Dave and Roberta to spend six months in Jamaica building a cabin on the property and supervising the planting of the coffee. The elevation of the surrounding land was just high enough to get government certification for Blue Mountain coffee, which even back in the 1970s was selling for something crazy like eighteen dollars per pound. Thus persuading my father to become a gentleman farmer, where he would earn his pension from abroad. Daddy never told me that his friends were there in Jamaica, building a house. But I knew they were, because I had seen them pictured in the slides I developed when he came home from his trips to the Caribbean, every two months or so. As an architect’s daughter, my job was to catalogue the hundreds of slides my father shot compulsively on his Pentax camera, detailing rooflines, corners, and facades of buildings. Photographs of flying buttresses on European churches; of Scottish gingerbread on West Indian cottages; of half-constructed apartment complexes and office buildings he had designed, lying naked and exposed on muddy lots. Occasionally, a random image of a human being—me or one of my sisters, my mother or some other pretty woman—would break up a long series of cornice detail.

I thus saw the cabin arise from the jungle floor in Ektachrome, from the laying of the stone foundation, to the framing and the raising of the tin roof. I saw Dave standing with his hands on khaki shorts next to our green dune buggy full of concrete blocks. Roberta standing among dark-skinned country people at the building site, machetes at their sides. The both of them bathing naked in the river that ran next to the property. My father, smiling broadly next to his friends, a roasted breadfruit in his hand.

The farm was located in a speck-sized hamlet in Portland Parish, a couple of miles inland from the coast on the eastern, lushest part of the island. During my adolescence, we would spend a few days there on family trips to Jamaica. It was what my aunt in Kingston disparagingly called “the bush.” No electricity or running water. Not even a standpipe by the road. But the land lay along a spectacular length of the Spanish River. There were seven waterfalls and seven natural swimming pools, the deepest of them with emerald water that eddied in perfect swirls as it approached the giant rocks nested in the river. At night, the shrill of West Indian crickets drowned the sound of the rushing river below.

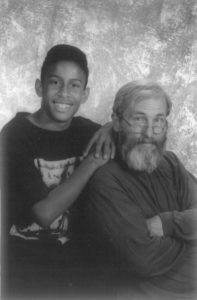

David (standing) and Roberta (seated in middle), circa 1976

It was breathtaking. But my sisters and I were thirteen, fourteen, and fifteen years old then, so of course we hated it. The funky toilet and the mosquitoes and the pitch black of night blinded us to the jaw-dropping beauty of the place. We forgot to look up at the stars studding the velvet sky, and instead played cards dejectedly by kerosene lamp, consoling ourselves with the knowledge that we’d soon be back in civilization at our uncle’s house in Kingston.

I did the backward math, and figured the kid must have been conceived there, at the farm. I imagined some free-love, post-river-bath ménage à trois against the massive rocks lining the river, or maybe on one of the tie-dyed mattresses in the sleeping loft of the cabin. At least I hoped that was the case. Or how else could David Baird still be friends with a man who’d screwed his wife?

The baby was crying full-steam now. I handed him back to my father. I can’t recall, some forty years later, if I told him straight out or just communicated in other ways that I considered this son his business, not mine. I do remember that I didn’t speak to my father for many weeks after that. In true teenage fashion, I even managed to be upset with my mother.

“Why doesn’t she leave him?” I once asked my father’s sister indignantly.

“Love is complicated, and marriage comes with obligations,” my auntie replied. “You’ll understand when you’re older.”

II.

I didn’t see my brother, Shawn, again until years later, when I was in college and on a visit home to Ohio. It must have been summer, when he and his parents were in town for the annual crafts fair. He was a cute kid of six or seven, with a phlegmy voice that managed to be high-pitched and gravelly at the same time. He was swinging a stick and talking a mile a minute. But the truth was that I didn’t really think much about him again until he was fourteen and I was twenty-eight and getting married. By then, I thought that I’d resolved my anger at my father. He was the person who most made me, me—the man who taught us to be proud and confident black girls in the buttermilk of the all-white schools we grew up in; the parent who left me gifts of Amiri Baraka poems on my desk in the morning; the man who fed my sisters and me the benevolent fiction that we were descended from African royalty. I resolved my anger by telling myself that while my father may not have been a good husband to my mother, he had still been a good father to me.

And I did it by boxing up the fact of my half-brother and filing him away, somewhere on a high and distant shelf. For years, no one knew I had a brother. Not my high school girlfriends. Not my college roommates or my best friends from law school.

My wedding was in Jamaica, where I knew it would be from the time I was old enough to imagine such things. Daddy had by then abandoned his architecture practice in Ohio in a state of debt and moved back to Jamaica. He pleaded with my mother to accompany him, but she declined, and their twenty-seven years of marriage effectively came to an end. Because nothing with my father was easy or straightforward, he’d rented a house high up on a hill outside of Montego Bay, at the end of a road cratered with potholes that wound precipitously around the mountain. My father considered the treacherous road a certain kind of security against thieves who wouldn’t want to haul ass down it at night. And, of course, there were the spectacular views his hill retreat obtained. My father was an aesthete, a lover of beauty in all its forms. But, for him, nothing surpassed the splendor of Jamaica’s Blue Mountains, viewed from two thousand feet.

When my fiancé and I arrived at Daddy’s place at the end of a teeth-rattling ride, my brother, Shawn, was there on the porch, petting the dogs. He’d lost his scrawny look and was now a rangy teenager, modest and quiet. He had my father’s handsome face and, unfortunately, his feet. Having bad Braithwaite feet myself, I immediately noticed the big toe jutting leftward. I hope that I hugged him, but it could very well be that I shook his hand like a stranger. I’ll admit I was pissed. The first question I asked my father when we were alone was whether Shawn would be coming to the wedding. I didn’t want my mother to have to explain anything or anybody on her daughter’s wedding day. My look said, “Don’t you dare embarrass Mummy.” Daddy exhaled a Jesum Peace with a sideways swerve of his neck, as if avoiding a blow, and took on that half-irritated, half-hangdog look he wore when one of the too-many women in his life got on his case.

And so Shawn shipped out for home before I walked down the aisle. My sister Susan gave me a hard time about it later. For years, she’d urged me and my other sister to get to know our brother. Susan had stayed in Ohio for college and had grown close to Shawn from the time he was a little boy, visiting the Bairds’ place occasionally on a weekend. Mud City is what she called it.

She was right, of course. I felt like shit about it two years later, as I watched Shawn and a trio of male cousins haul Daddy’s coffin on their shoulders at the end of his funeral service in Kingston. By the time my father died at fifty-nine of heart failure, his son was on the cusp of seventeen. Handsome and slender, with a long nose that flared at the tip. The same broad smile of my father’s that lit up a room. Still a boy, he looked stoic through the funeral, while my middle sister and I bawled.

Although I didn’t know it at the time, Shawn was by then well acquainted with Jamaica, where my father took him for several weeks every summer. They would spend a week or so with the cousins in Kingston, and then time alone together in Portland Parish, at the cabin his parents had built. There, he swung on jungle vines over and into the river, like Tarzan. He was used to the forest, and knew all about kerosene lamps. The real culture shock for him was Montego Bay, where bonfires in oil drums illuminated sound-system parties that boomed menacingly into the night.

Years later, he would tell me that for him, our father’s death was an experience perhaps less of grief than of unmooring. Shawn knew, of course, that John was his real father, but he figured in his life more like a favorite uncle: there were trips into Columbus to the toy store and, as an older boy, to museums and to football games. But most of all, it was our father who kept him tethered to a black culture that he didn’t experience directly but, as a teenager, desperately longed for. He remembered our father’s funeral as coinciding with another milestone of his youth: the release of Bob Marley’s Legend compilation. In the wake of our father’s death, I didn’t inquire into the particularities of his cultural orphaning; I simply assumed it to be the case and, with not inconsiderable guilt, figured that he could use some extra mothering.

I tried to make up for my years of neglect. That fall, when Shawn was a senior at his small rural high school, I took him to tour colleges on the East Coast. We visited a couple of state universities, and a few smaller colleges in the suburbs of New Jersey. He nearly freaked when we drove through a neighborhood of McMansions in Morristown. “I don’t belong anywhere like here,” he said. It took me a minute to remember that he was raised by starving artists in a house without a flush toilet. My sisters and I had grown up in an upper-middle-class suburb of Columbus, in a house designed by a student of Frank Lloyd Wright. There was more than a mother that separated us.

Roberta tried, nicely, to tell me that Shawn wasn’t ready for college. But I was a sister on a mission of uplift and recompense. I was going to get him into a good college and on a professional track. Had he taken the SATs? (No, his guidance counselor said the ACT was sufficient.) What were his extracurriculars in school? (Deejaying parties for college kids at Ohio University.) I was busy ordering him the six-hundred-page Barron’s Compact Guide to U.S. Colleges when my brother announced one night, during a visit to me in Brooklyn, that he had decided to move to New York City after graduation, to launch his career as a rapper.

“You’re going to do what?”

“I’ma launch my career in the music industry.”

“And what about school?”

“I figure I can take some classes part-time at Medgar Evers College. I applied and got in.”

“Medgar Evers College? You mean Medgar Evers at the end of the No. 1 line, deep in the heart of central Brooklyn?”

“Yeah.”

“And where would you live, exactly? I’m pretty sure that’s a commuter school.”

“I figure I be kickin’ it here with you and George,” he replied, with the kind of eager smile a puppy offers when presenting himself at your feet. “Here” meaning, I supposed, the two-bedroom apartment I shared with my husband and our six-month-old baby in Park Slope.

I knew all about Shawn’s aspirations to music celebrity. He had written whole notebooks full of rhymes—his “flow,” he called it—which he carried around at all times in a canvas backpack in case inspiration struck. He recorded his rhymes over beats on cassette tapes and handed them out like jellybeans to anyone who might know someone. I played the tapes in my car on the long drive home to Ohio once. To my relief, the lyrics were ghetto but not gangsta—more liberation than libido, and thankfully bitch– and ho-free. I was hardly an expert on rap music, and just old enough to prefer my music with a little melody. But I wasn’t convinced that my brother had the kind of flow that made for a six-figure record contract.

Shawn was by then in the full thrall of hip-hop culture, with an extra tight hug of overcompensation for the rural white community from whence he came. He had the pager, and the half-dip walk nearly perfected. In homage to his Jamaican roots, he sported dreads and nodded to Bob Marley’s Exodus on his Walkman, along with Wu-Tang Clan. Growing up in an enclave of Midwestern hippies, Shawn wasn’t the only one with an unconventional family arrangement, but he was the only black kid with two white parents. By the time he was in high school and regularly getting into fights with redneck kids from the next town over, it was easier all around to just tell people that he was adopted.

I steered clear of the make-it-as-a-rapper part of his announcement and focused instead on the matter of my might-be-half-white-but-looks-black baby brother moving to central Brooklyn at the height of the NYPD’s campaign of “broken windows” policing. I’d finished law school and was a public defender for Legal Aid by then. I knew that black boys like Shawn got arrested and held on Rikers Island for days—sometimes months—just for smoking reefer on the street.

I didn’t tell him no outright. Instead, I broke down the odds that a black boy his age would get arrested or, at the very least, stopped and spread-eagled against a wall on the streets of Brooklyn. I explained the dormitory rules that would obtain at my house after he moved in: Home by 10:30 p.m. on weekdays, 12:30 a.m. on weekends. No weed smoking; no friends hanging at the apartment after 7:00 p.m. And he’d be sharing the back bedroom with his baby niece.

It broke my heart, just a little bit, to do it. He just wanted to be with his people, was all. But I was relieved when his mother told me he’d be joining City Year, working on a community service project in Cincinnati. Not that Cincinnati was safe. Just a few years before, the police shot a black nineteen-year-old boy in the back. But compared to New York? It was safer. And he was a naïve kid without street smarts. It was for his own good, I told myself.

Shawn would eventually get his degree from the University of Cincinnati and settle down with his college girlfriend, a lovely young woman from India whose parents had, like mine, immigrated to the U.S. to finish their graduate studies. Shawn became a sought-after videographer, his specialty being slow-motion shots of athletes, the beads of sweat sailing slowly off their foreheads. At some point, a few years before he and Sumir got married, the two of them broke up for a time. I asked my brother what happened. He shook his head to the side in a way that reminded me of our father, looked up at me and said, sheepishly, “I screwed up.”

I trained him with a hard gaze. Don’t be a shit like Daddy is what I was thinking. My father’s infidelities were still a trigger for me. I’d grown into a woman who distrusted men as a result, and ultimately married a man who was as different from my father as night was from day. I wrestled down the instinct to pop the side of my brother’s head. Young people in their twenties broke up all the time, after all. And Shawn wasn’t the killer playboy that my father was. His was a different brand of charisma altogether, feckless and sweet.

“So then, go get her back,” I replied evenly.

Their wedding was a full-scale Indian extravaganza. No white horse, but there was a ceremony of greeting between the families, in which my brother walked down the driveway of the Dayton Marriott wearing a crown with a curtain of gold beads that obscured his face. The bride’s family and a brace of drummers welcomed Shawn’s kin at the entrance to the hotel, where we were invited to dance in turn with our peer in-laws: sisters with sisters-in-law; cousins with cousins-in-law; and aunties with aunties-in-law. The parents went first. I hadn’t seen David Baird in nearly thirty years. He was an old man now, with a long white beard and sclerotic knees. But his face was a study in joy as he danced in a long Indian tunic. Later, at the reception, my sisters and I were seated with two slightly bewildered-looking white women in their forties. In the course of introductions, I learned that they were David’s daughters from a previous marriage, before Roberta, and eventually gleaned that Shawn’s white half-sisters didn’t know anyone else in the room, either. Through half-references and insinuation, I pieced together that two of the three daughters had sided with their mother in the divorce, and had little to do with their father’s new family. It made me feel a little sad for them, and happy that I had gotten over it—the infidelity—on our side of things.

“Shawn’s a wonderful person,” I whispered to one of the sisters during the first dance. “He’s going to make a great husband and father.”

But the equal truth was that, until the wedding invitations had arrived a few weeks earlier, I hadn’t known if my brother spelled his name with a w or a u in the middle.

III.

One late winter afternoon last year, I learned that David was dying. By the time I reached Shawn, his father had already passed. I called Roberta the next day to convey my condolences. He went fast, she said, and for that she was grateful, though I could hear the crack in her voice. On a chilly day in April, Susan and I flew to Columbus and drove two hours south to the memorial service. It was held in a simple country church, set against a lawn dotted with early spring snowdrops and purple hyacinth. The pews were full of young and old artists who’d studied with Dave at the Foothills School of American Craft, which he had founded. There was no preacher and no singing of hymns, as David wasn’t a believer in that kind of God. His only son—my brother, Shawn—delivered the eulogy. Then, one by one, some forty people in the congregation of one hundred folks rose to say something about David. Together, they knit a story of an iconoclast’s life.

Everyone, it turned out, called it Mud City. Dave and Roberta first laid their claim to the land in 1970. In the middle of February, they pitched an A-frame tarpaulin tent in the woods with a kerosene stove in the center and set about building not shelter first, but an artist’s studio. The house construction began a year or so later, with Dave and Roberta hauling concrete blocks up the hill on their backs, because even a four-wheel-drive couldn’t make it up the trail through the woods that served as a road. Given its construction crew of two, the house was not really a single structure as much as an accretion of nooks and crannies built over time. Dave and Roberta would later build another house of improved design, with large windows that let in plenty of natural light and a spectacular deck that looked over the valley of woods.

David and Roberta, at the founding of Mud City

Both the first and the second house were entirely off the grid. (If you don’t have to be beholden to the government, reasoned David, why be?) Dave tapped into the Utica shale that lay beneath his land to siphon natural gas, which they used to heat the house and power the generator. Several funeral-goers told stories about the so-called septic system—a compost toilet that was theoretically self-cleaning. The solitary house of artists eventually grew into a colony of other artists’ homes, with a handful of other stubborn souls building their own dwellings out there in the woods. Down the hill a ways and to the left was a gay couple—both retired theater actors—and beyond that, the homes of a painter, a ceramicist, and a photographer. Until his death, David presided over the community as Mud City’s unelected mayor.

Shawn grew up wandering those dense woods as a child, learning to distinguish bear from deer scat and catching frogs as friends. When he was no more than seven or eight years old and Susan would come to visit, he would meet her at the bottom of the road and drive her up to the house in the family’s ATV. While most kids went to the country for summer camp, Shawn did the reverse: he roughed it in the backwoods during the school year, and in the summers decamped to the city—to Chicago or Dayton to visit his cousins. Some of those now-grown cousins were present at the funeral. There were wry half-references to politics that made clear that Dave Baird was the liberal black sheep in a family of white conservatives. His kin painted a portrait of an eccentric but loving uncle who could expound on the state of the universe for hours, but with whom you didn’t dare discuss domestic policy. Shawn’s eulogy closed this way:

As I grew into a young man, and then a father myself, so grew my understanding of what my father did and what he made—what he achieved in life, beautiful and awe-inspiring. He was so driven as an artist, so motivated by a philosophy, that he basically eschewed the trappings and comforts of society and, at great sacrifice, struck out into the woods on his own to make a studio and to make his art. To make it all on his own terms. It was from this place of confidence and knowledge—this “zen”—that he sought out the harmony of nature in his own life. It was that harmony, that composition of nature, that inspired his art, and his art was his life.

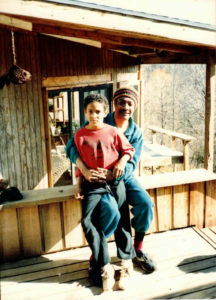

After the service, the guests gathered in the basement of the church, where Roberta had set up a small altar with family photographs and some of Dave’s artwork. There was a formal portrait of Dave in middle age with Shawn as a teenager, resting his arm on his father’s shoulder. A snapshot of Shawn at the age of nine or so in a red sweatshirt, wedged between his parents on the deck of their home.

Shawn and his father, Dave, c. 1993

Shawn and our father, John, c. 1985

I recognized that second picture. Shortly after my father died, I found a cache of old photographs in his belongings. There were a series of black-and-white photos of my father in Mud City, holding a tortoise aloft while my two-year-old brother peered into the shell, his lovely toddler face alternately full of wonder and apprehension. Among the bundle was a photograph of my dad on Dave and Roberta’s deck in the 1980s; he was wearing a red, green, and gold Rasta tam on his head and held his son on his lap. Shawn’s clothes and the light that hit the deck were identical to those in the photo that now graced the altar table. My father must have taken it, that photo of his other family. Contemplating the image as an adult, and now a mother, I felt a weird sense of pride that my father had done more than sired a son outside his marriage—he’d stayed continuously in Shawn’s life, as a father figure, if not a full parent. I also felt gratitude and respect for the white man who fully fathered Shawn, at a time when interracial adoption—let alone whatever you called their unique family circumstances—was rare.

The whole memorial service, in fact, filled me with a strange kind of melancholy joy, to realize how much Dave and my father, John, had shared: a disregard for convention; a reverence for the handmade; a passionate embrace of the backcountry; and, of course, a fierce love for their son. I was sad that I had deliberately missed knowing the extraordinary family in which my brother was raised. But in a flash I understood that it had taken my own father’s death, some twenty years earlier, to allow me to really embrace my brother. My father’s passing somehow freed me of the need to continue to punish him for his transgressions, by keeping his son on that shelf. It was one of those painful paradoxes of adulthood, in which a wrenching loss of someone you love, while closing a door on one relationship, opens you to others.

Things had come full circle in other ways, as well. Whatever rancor my mother had felt about her husband’s son had also resolved, and she now regarded Shawn, his wife, and his kids as extended family. Both David and John were gone, but Shawn was writing his own story of fatherhood. My father’s love for his children managed to be simultaneously intense and self-referential—his hugs were as much about his need for reassurance that he was deeply loved as they were about ours. Shawn’s parenting was more purely devotional. He was the kind of dad who would patiently skip rocks in a creek with his kids for hours, and who changed diapers expertly under trees when necessary.

His eldest son, Shalin, was the spitting image of my brother at age seven. Shalin fidgeted continuously throughout his grandfather’s memorial and, as soon as it was over, scampered off to play in the woods behind the church cemetery. I asked if we had time to drive over the ridge to Mud City, so that I might see for the first time the hand-hewn house in the woods that I’d heard so much about. But the sun was setting by then, and we had a long drive ahead of us. The last photograph I took at Dave’s service was of my nephew, who reappeared at the end of the day after a long series of cup-handed calls by adults into the woods. He emerged from the trees, as my brother might have done at the same age, with a stick in one hand and a bird’s nest in the other, his smile as wide as the Ohio Valley. I took it as a sign that I was meant to know my nephew as a child, and to settle for loving my brother as a man.

Tanya Coke is a civil rights lawyer and writer. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Root, and USA Today. She is currently working on a graphic novel about race and suburban motherhood.

All photos courtesy of the author.