By TED CONOVER

If it weren’t for the detailed map in my hands—a page of the New Hampshire Atlas and Gazetteer, from DeLorme, with the small state divided up into more than thirty spreads—I’d have had no idea that a road existed here, half a mile from our house. And in fact, the atlas has oversold it: Brown Road does exist, but not in a condition where you could drive a car or even an SUV down it. Nor a mountain bike, unless you were hardcore and could lift it over fallen trees, slide it under branches, and skirt some soggy bogs.

My ambition was simply to walk it. I’d asked around the village where my wife’s family has an old farmhouse, and nobody appeared to have done that in some time. One woman remembered traveling it on cross-country skis when she was a girl, but that was twenty years ago. An 80-year-old man, who also grew up here, told me he drove it in his dad’s truck, when he and his father went out to hunt a fox. The village stopped maintaining the road in 1932 so he must have been, well . . . less than ten years old.

A third person warned me to be careful of bears back there this time of year. I’d have suspected she was just pulling a city slicker’s leg, except that my daughter, 10, did see a bear behind our house in July, the month before. As I left our house, on foot, I picked up a solid walking stick that has leaned against the entryway for as long as I can remember. I wondered what would be the best way to use it on a bear.

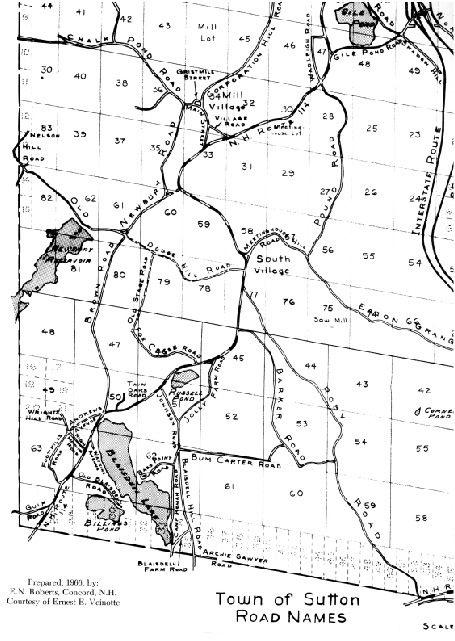

After ten minutes on blacktop, I stepped off onto a steep stretch of dirt road leading to the abandoned road. This kind of walk, I knew, was also time travel. Every road tells a story of a particular historical period, of a place and people. Brown Road’s story is of rural New England in the mid-nineteenth century. That’s when Edward Brown, a farmer, proposed to the town of Sutton, New Hampshire, that they establish a proper road, a mile and a half long, connecting his property to the village center, on the one side, and to an established road to a nearby town, on the other. Brown’s land was already connected to both villages less directly, via Fox Chase Road (the area was known for foxes). Brown’s new road would be “three rods wide” (a rod was five and one-half yards) and maintained by the town. The town must have agreed it was in the common interest, not merely in Brown’s, to build it, for they agreed to do so on March 8, 1853. As part of the deal, they paid Brown and other abutting landowners damages for taking their land: Perley Anderson received $150, Nathan Burpee $60, Dr. Dimond Davis $50, and Brown, himself, $75.

As I headed up the dirt road, I passed a spot in a wall of trees where an even bigger throughway, Dodge Hill Road, established before the American Revolution, had once crossed Brown Road. Dodge Hill Road had been part of a major regional route between the Merrimack River and the Connecticut River. But, though I paused to examine the woods directly where Dodge Hill Road should be, I saw nothing but trees and a few roadside raspberry bushes. I paused to eat some ripe berries—procrastinating, actually, because ahead I could hear a lawnmower. The road was now a cul-de-sac, effectively, and so deep in the woods that it felt like a private drive. The last house on it was suburban-style, with an expansive sloping lawn that I had to walk right by–a stranger on foot, probably the first one in months.

The mower was the riding kind and the man upon it, chugging away from me at an oblique angle, either didn’t see me or pretended not to, so I just kept walking, wary of unleashed dogs, glad I had the walking stick. Ahead was a thicket of vines and branches but I could see a narrow path through, a game trail. I ducked onto it, the shrubs rose up above me, and I was out of view of the house. Brown Road.

Though some parts were a washed-away mess and others were shrub-choked, most of the route was easy to follow. Stone walls lined it on either side, as is common in New England. Farmers hauled rocks from their field to the edges, where they became fences. Parts of the old road had stone culverts alongside, too; they once drained away road-destroying moisture. At first my footprints mingled with two kinds of tracks in the dirt—ATV (all-terrain vehicle—the small four-wheelers that rural kids love to ride), and moose. But then those disappeared. The woods on each side were dark, heavy, and quiet—so quiet that when I flushed a big, heavy bird ahead—a pheasant, or a grouse—the commotion made me jump.

There were no buildings, no farms—no visible ruins of any kind apart from the road. The 80-year-old I had consulted, local historian Carlton Bradford, had said he hadn’t seen a farm here either, on his visit in the 1930s. That meant that in the 80-or-so years since Farmer Brown had convinced the town to build a road across his property, the farm had vanished. It fit with what I had heard was a main reason for the abandonment of so many rural roads in New England: abandonment of the farms.

Thirty years before Brown Road was established, Sutton and the entire region had begun a slow decline.

From a peak of 1,573 people, reached in 1820, the town lost residents for more than 100 years. Most of rural New England did: the Great Plains was opening up, and its rich soil and blessed lack of trees and rocks made New England, though picturesque, seem a farmer’s nightmare by comparison. At the time, of course, New England, just like the Amazon rain forest, had seen major deforestation in the creation of farmland. Trees were cut, then burned. Oxen pulled stumps from the earth and helped to clear the endless numbers of stones; the stone fences (which still exist), alongside roads and between fields, were an obvious solution for what to do with them. It must have been a Promethean labor, to clear the land. And utter heartbreak, finally, to leave it all behind—though easier, no doubt, if you were hungry and poor.

Brown Road ended in a marsh; I bushwhacked to get around it. A hundred yards further on was civilization: a few houses and then the road that the original farmer Brown had aspired to reach, now known as state Route 114. The landowner who had been compensated for Brown Road at this end so many years ago was Perley Andrews, and just before I reached the bicycle I had left at Route 114, I saw a street sign for Andrews Avenue. I stashed my walking stick in the bushes near it.

It was a quick, two-mile ride up Route 114 to the intersection with Dodge Hill Road—the route whose other end I had sought at the beginning of my hike. I parked my bike and began a second walk that would take me back where I started. Like Brown Road, Dodge Hill today begins as nicely graded dirt. But once it passes the fourth or fifth (and final) house, everything changes. The road shrinks and decays as it heads up the gentle hillside. Views disappear; woods press in on both sides, seemingly intent on erasing the road.

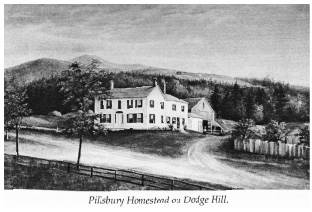

It took only about fifteen minutes to reach the site of the area’s most famous homestead, that of the Pillsburys. Jack Noon’s valuable The History of Sutton, New Hampshire, Volume II, reproduces a lithograph of the “Pillsbury Homestead on Dodge Hill” on its cover: It’s a beautiful three-chimneyed, two-story white house, with a barn in back, lawn in front, and rail fence alongside a field across the street. All around it is open land; other farms are visible on the hillside behind. It sits at the junction of Dodge Hill Road and another abandoned route, and that’s how I figured out where it used to be.

All that remains is an indentation, known as a cellar hole, where the basement used to be. There are no structures at all, no view, no evidence of human activity apart from scattered stone walls and the vestigial road. Woods have reclaimed the fields. The Pillsburys arrived in Sutton in the late eighteenth century, but during the nineteenth, many got out. Two of the homesteaders’ grandsons, George Alfred Pillsbury and his brother, John Sargent Pillsbury, left the area for Minnesota, a good move: George became mayor of Minneapolis, while Charles started a flour company that became very, very big.

It was another bushwhack to get to the end of Dodge Hill Road. After checking for deer ticks (the settlers didn’t have to worry about Lyme Disease), I walked into our village of Sutton Mills. The handsome brick town hall was a gift from the Minnesota Pillsburys, but inside there was little information on the Browns. Across the street in the town library, an old book revealed a bit more: David, born in 1801 in nearby Wilmot, had married Mary, from Boston, in 1824. They had eleven children. After a short walk to the town graveyard, behind old Union Church, I found the couple’s double gravestone. Mary died on July 31, 1882, at age 78. David died on September 6, 1893, at 91. Only one child is buried near them—their daughter, Elizabeth, who died April 8, 1865, at age 20. Her headstone reads, “The beautiful has vanished and returns not.”

At the bottom of the Brown’s gravestone was verse, hard now to read but still legible:

Life’s race well run,

Life’s work well done,

Life’s crown well won,

Now comes rest.

Back in the Pillsbury town hall, as it’s known, inside a giant walk-in safe, there’s a typescript volume called “Sutton Roads” that contains brief descriptions of each. It begins with an index of them all, in alphabetical order. It’s an old-fashioned carbon copy, so everything’s kind of muddy, except for an entry off to the side of the only road name beginning with “I,” which is Isaac Masten Road. This new entry was added some time after “Sutton Roads” was compiled, in 1972; it was entered using an electric typewriter. The road itself, I know, was built in the early 1960s. It’s less than a mile away. It changed everything in this part of the state. I wonder how it got added to the list; I picture two clerks in hot discussion, one saying, well, it’s not really one of our roads, is it? And the other insisting, if that’s not a road, I don’t know what is. You have to add it in.

The second clerk won. The final entry is “I-89.”

Ted Conover is the author of five books of nonfiction, including Newjack: Guarding Sing Sing, which won the National Book Critics Circle Award in 2001 and was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize.

Click here to purchase Issue 01