By LUCHIK BELAU-LORBERG

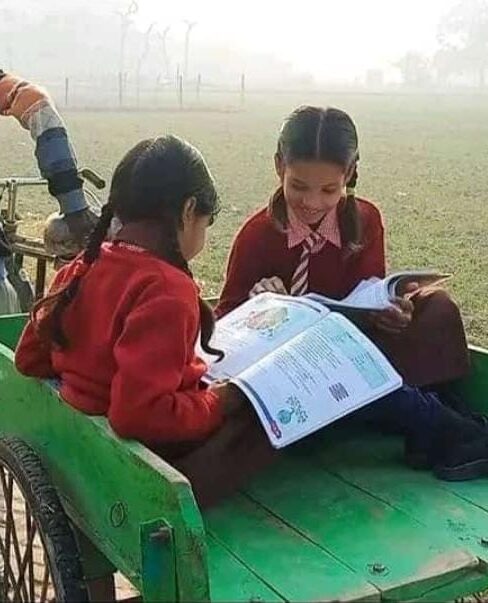

Photo courtesy of the author.

Shrewsbury, MA.

There’s a family seated at a window booth across the aisle from us; the youngest daughter keeps attempting to pronounce “syrup.” I wonder what she’ll remember of this breakfast in five years’ time. Maybe today she reminds you of me.

My earliest memories of an IHOP are sticky: the yellow walls seeping into the faux-leather booth seats; a stain on the carpet. All this beneath a crumpled-looking roof in a parking lot below the I-90 on the outskirts of Boston. Still, I could order as many blueberry-chocolate chip pancakes topped with creamy-fruity smiley faces as I wanted. The point wasn’t that I particularly liked eating the smiley faces, but that there simply were and could be smiley faces. And, in the meantime, before my hot cocoa (also with whipped cream) arrived, a crate of Smucker’s jam packets to stack and suck on awaited on the tabletop. This Ur-IHOP was sweeter than home, overtly abundant, happy, and these qualifiers felt, at the time, somehow synonymous. At home, mornings typically consisted of milky buckwheat porridge and cheese curds. Here, breakfast came with a set of primary-colored crayons.