When MAURICIO RUIZ told MELISSA FEBOS he was interested in addiction, she said he could borrow her books. “I have done a lot of research,” she said. “You’re welcome to use the material.” They stood in the lobby of the Old Capitol Building in Iowa City after the 2024 Krause Essay Prize ceremony. Ruiz plucked a praline from a tray and told her he missed Belgian chocolate. Febos pushed up her glasses and said, “Do you know anything about the Beguines?”

In her memoir The Dry Season, Febos describes her commitment to abstain from dating and romantic relationships for a year, and examines her life in contrast to famous women who chose celibacy. As readers witness the evolution of her relationships, her creative practice evolves as well. The question emerges, “How do we not lose ourselves in love?”

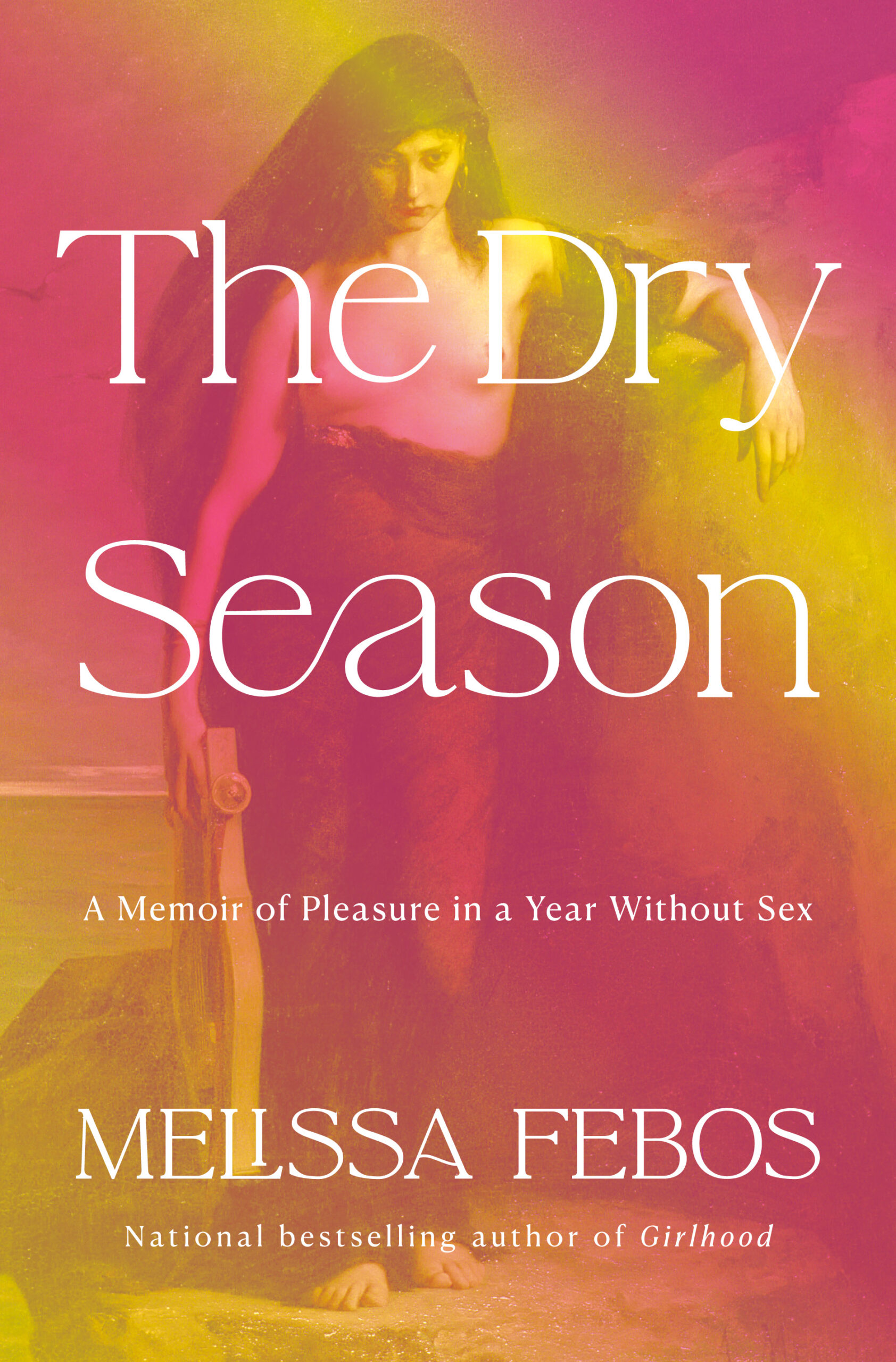

Ruiz spoke with Febos about choosing Sappho for the cover of The Dry Season, the brain’s neurochemicals when in love, why she embarked on a year of romantic abstinence, and more.

Mauricio Ruiz (MR): Charles Auguste Mengin’s painting of Sappho was a constant during the year you describe in The Dry Season. When did you first see the painting, and how did it become so significant for you?

Melissa Febos (MF): I encountered the painting first on the internet years ago. I might have even been in my 20s. Certainly, by my 30s, I was aware of it and felt an immediate connection to it. I must have had a little print-out of it, and I kept it on my corkboard behind my computer for a long time. There was just something about her. As I say in the book, she’s a tall, sulky lesbian, which is totally my type.

She looks so exhausted, and for someone who was always writing love poems, I identified with her. I thought, “I too am very exhausted by love and writing about love.” So I had a crush on her and identified with her at the same time, which is an experience I’ve had many times. Often, identification and attraction come together for me.

But then, when I was writing the book, she really became the symbol of both the way she was proof, as a work of art that I had romantic feelings toward, that you could experience the sublime outside of a romantic relationship. Just through the course of daily life and through other passions, but she was also a symbol of the character of Melissa, as I was writing her in the book.

MR: You’ve said that The Dry Season is about the “deep satisfaction and liberation of cultivating an intimate relationship with oneself.” Why did that year not become two years, three years?

MF: The simplest answer is that I met my future wife. Sometimes I think back honestly, and she knows this, and I think more time would have been even better. But I do think I was ready. At the end of that year, I honestly thought I didn’t know if I ever wanted to be in another romantic relationship. I was so happy and felt so complete and contented on my own that I could only imagine that another person would disrupt or diminish the experience.

I really was not looking. And then I just met her, and the course changed, and I had done so much work in that year to change my thinking and myself and my ideals and my relationship to love, but I couldn’t really grow much further without actually practicing it with a person. It’s like reading and thinking about dancing in a new way, but you can’t get good at it until you actually start dancing.

I think I was ready for the kinds of growing that I could only do in conjunction with another person.

MR: When there is love, infatuation, and desire, dopamine and oxytocin are released in our brain. Do you think your brain’s neurochemistry changed over that year? How?

MF: I think it must have. When we dramatically change our thought patterns and our behaviors, it changes our brain. I think I had a very well-worn neural pathway: this is where I look to for these kinds of feelings, for happiness, and for some self-esteem, and I effectively rerouted that over the course of that year.

It doesn’t mean that I didn’t get to enjoy the fun sort of dopamine feelings like when I fell in love with Donika, but that I wasn’t totally focused on that and I didn’t abandon all the other places in my life where I got good brain chemicals and a sense of satisfaction or a sense of self. I maintained my friendships and my other practices and my artwork and my alone time, and I maintained the intimacy with myself, which I had never done in the past. I’m sure that there is a correlation in the brain that reflects that, whether we know how to see it or not.

At the end of that year, I felt whole. I was ready for the kinds of growing that I could only do in conjunction with another person.”

MR: You defined the concepts of celibacy and abstinence for yourself: you could pleasure yourself, but you could not flirt. Was it ever an option to go as far as to also give that up, self-pleasuring?

MF: Yes, it was. And I think if it had seemed correct, I would have done it. I was not opposed to the idea. I went to this meeting for people who are sex and love addicts because I wasn’t sure if I was one. Some of the people there talked about how everyone in that form of recovery had to define their own abstinence. And a lot of people defined part of their abstinence as refraining from masturbation. And I thought, Should I do that?

But then pretty quickly I thought, No, I’ve never done that compulsively. And the things that have marked my relationships that have gotten me to a bottom had to do with performance, inauthenticity, people-pleasing, doing things that I didn’t really want to do because I thought someone else wanted them. None of these things were evident in my auto-erotic relationship.

It was actually a very wholesome instinctive relationship that I’d always had, that never felt vexed in any of those ways. And I ended up thinking, Wow, I wish that my sexual relationship with other people was more like the one I have with myself. I decided not to have that [refraining from masturbation] be a part of it, which I knew would be sort of ridiculous to some people, but I was on a very individual mission. There was something specific that I wanted to change about myself, and I had to refine my concept of what that was over time.

MR: People often ask if you do things to write about them, and you’ve said, “I just live myself into corners and then have to find a way out.” Many writers would like to do just that. How do you live yourself into corners in your day-to-day life?

MF: I was born with a set of very extreme appetites, which is partly what I write about in The Dry Season. I am an extremist by nature.

My drives are so strong that they overwhelm reason. A lot of the corners I have lived my way into, if I had intellectually thought about them, I would have decided against it, and thought, “That’s a terrible idea. That sounds like it’s going to be very painful and hard to come back from.”

But instead, I have this very sort of feral, inexorable set of drives inside of me that get me into these places, against reason, and then I have to write my way out. I can’t quite recommend it. I know it can be fun to read about, but it’s not very fun to live. Still, I have no regrets. Writing is a form of alchemy that gives very bad decisions value in hindsight, which is part of why I am devoted to it.

MR: You chose to be celibate. There was a choice. The involuntarily celibate people, do you think they could reframe their life situation and see it as a choice?

MF: I mean, the short answer is yes, I do, but I want to be very cautious about speaking for other people’s experiences because I can’t with any authority.

I did come to the insight over the course of having this experience and talking to lots of people about it, that the people I spoke to who were in long-term involuntarily celibacy spoke about it very similarly to how I spoke about being in somewhat involuntary, never-ending relationships. We were both caught at opposite ends of a spectrum. I think that people who live toward extremity have more in common than they don’t.

I had more in common with long-term involuntary celibates than I did with people who had a more balanced relationship to love. It’s interesting that recovery communities for people who identify as sex and love addicts (which I don’t) include those who live at the opposite extreme. Some call themselves “sexual anorexics.” And those people are in the same recovery program and have the same solution to people who are in compulsive relationships, because both are problems of extremity. I think we are all trying to get closer to the middle. We’re trying to get to a place where we feel whole on our own, and we can enter into partnerships with other people with full autonomy and choice. Dependency is not the glue that holds us together. When I was deciding to publish this book, I thought, Oh no, the people who are involuntarily celibate are going to find this so offensive. And then after I finished writing it, I thought, No, we actually kind of have the same problem. And I can trust that they’ll see that we are people who are not living in accordance with what we want and what we believe, and we want to figure out how to change that.

And hopefully, my experience will be helpful, because my goal was not to meet my wife or have a relationship.

It was to be able to make more conscious choices and to be more aware of why I was making the choices I was making. At the end of that year, I felt so whole and complete, and I do think that that’s part of what qualified me for a different kind of relationship. I didn’t feel like I needed it at all.

Writing is a form of alchemy that gives very bad decisions value in hindsight, which is part of why I am devoted to it.”

MR: In The Dry Season, you describe aspects of your life you explored in your second book, Abandon Me. You wrote, “[the book] detailed the violence with which revelation must occur to me in order to puncture my resistance to real change.” Is that violence in the revelation still a must?

MF: I would like to say no. I think one way of looking at my life is a timeline of my fixation with holding onto something until I absolutely can’t anymore, and there’s a violent puncturing of my resistance. And it happened with drugs and alcohol. It happened with love and sex. It happened with exercise. I was a pretty compulsive over-exerciser for a long time until I injured myself so severely that I couldn’t walk for a couple of years intermittently. And that’s what it took for me to change my behavior. With each of those experiences, extreme pain was the only corrective that worked. I would love if I never had to experience that again. I would love it.

But experience has taught me that there might be other ugly bottoms in my future. Each one has been more and more gentle. And I hope that pace continues. I would like to never have to learn my lesson quite so hard in the future.

Melissa Febos is the national bestselling author of four books, including Girlhood—which won the National Book Critics Circle Award in Criticism, and Body Work: The Radical Power of Personal Narrative. She has been awarded prizes and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, LAMBDA Literary, the National Endowment for the Arts, the British Library, the Black Mountain Institute, the Bogliasco Foundation, and others. Her work has appeared in The Paris Review, The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, The Best American Essays, Vogue, The Sewanee Review, New York Review of Books, and elsewhere. Febos is a full professor at the University of Iowa and lives in Iowa City with her wife, the poet Donika Kelly.

Mauricio Ruiz is the author of two story collections, and this fall he will join the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. He’s the recipient of a writing fellowship from Granta, and his work has appeared in Asterix, The Common, The Rumpus, Electric Literature, The Masters Review, Words Without Borders, Letras Libres, among others. He’s been shortlisted for the Bridport and Fish prizes, and received fellowships from OMI writers (NY), Société des auteurs (Belgium), Jakob Sande (Norway), Can Serrat (Spain), and the Three Seas’ Council (Rhodes). He’s lived in Norway, Belgium, Mexico, and the US.