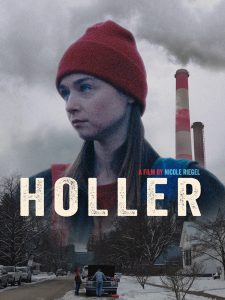

Film written and Directed by NICOLE RIEGEL

Review by HANNAH GERSEN

In Tara Westover’s bestselling 2018 memoir, Educated, a wildly intelligent young woman finds herself stuck working in her family’s junkyard, unable to leave her isolated Idaho town even as she longs to go to college. Public school is forbidden by her fundamentalist Mormon father, so she is homeschooled with her siblings and forced to scrap metal in illegal and unsafe conditions. Westover’s gripping story of escape captivated readers across the country, and I found myself thinking of it as I watched Nicole Riegel’s directorial debut, Holler, which concerns a young woman facing similar challenges.

Set in a small town in southeastern Ohio, Riegel’s realist drama follows Ruth (Jessica Barden) and her older brother Blaze (Gus Halper), as they undertake dangerous work in a scrapyard in order to pay for Ruth’s college education. Ruth and Blaze are practically orphans, left to their own devices while their mother, a recovering addict, does time in the county jail. Technically, Blaze is Ruth’s guardian, but he’s barely out of high school and still a kid in a lot of ways. His primary goal as surrogate parent is to make sure Ruth graduates from high school and attends college. He knows she’s smarter than most, and he also understands that she’ll be happier in college, where it won’t be considered odd to have a pile of books on her bedside table and to watch TED talks on YouTube. Maybe he also sees that she has the confidence to live away from home. Ruth may be bookish but she’s not meek; she’ll talk back to anyone who questions her abilities and sometimes she’ll talk back just out of spite. She’s an angry young woman, not only because she feels abandoned by her mother, but also because there’s a pervasive attitude in her community that intellectual ambition is pretentious and foolhardy. As with Westover, Ruth’s struggle to leave her small town is as much about overturning internalized expectations as it is about securing financial resources.

Ruth and Blaze are living below the poverty line and much of the action of the screenplay revolves around their various hustles to get by. We see Ruth and Blaze stealing trash for scrapping, usually under the cover of darkness. Ruth also makes extra cash by doing a friend’s homework for her. But it’s not enough. The rent is overdue, and the water had been shut off. Blaze is studying to pass a test to work in the local Aramark factory, which produces frozen pre-packaged dinners, but he and Ruth need money immediately to forestall eviction and buy food. Their desperate circumstances lead them to take on a more dangerous form of scrapping, which has them gutting abandoned industrial buildings to find copper and other valuable metals. These materials will be sold to buyers who will export it to China. Ruth and Blaze’s clandestine scrapping crew is literally hollowing out their local infrastructure to fuel a foreign economy, which in turn threatens the existence of their remaining factories. That this is occurring in a state that voted overwhelmingly for President Trump, a leader who promised, but never delivered on an infrastructure bill full of good-paying jobs, is not lost on Riegel. In an early scene, she gives us a tidbit of Trump’s campaign promises, heard over the car radio: “We’re going to bring jobs back for Ohio!”

Although Blaze and Ruth visit their mother (Pamela Adlon) regularly, they rely on their mother’s best friend, Linda, a manager at the Aramark factory, for advice and nurturing. Linda gives them food, including what looked to be frozen dinners from the factory, perhaps meals that were edible but not good enough to sell. Played by Becky Ann Baker, Linda is a tough but empathetic older woman. With her short hair and no-nonsense demeanor, she’s reminiscent of Frances McDormand’s Nomadland character, Fern. She even shares one of Fern’s most memorable lines, and one that McDormand quoted when she received an Oscar for her performance: “I like to work.”

Holler and Chloé Zhao’s Nomadland premiered in September 2020, and the two directors are mining similar themes as they look at the way globalization and a shrinking social safety net have affected ordinary people’s day-to-day lives. Both directors are also adept at mixing documentary elements with fictional narratives. Like Zhao, Riegel cast non-actors to play some of the smaller parts, and she shot the film in her hometown, the kind of out-of-the-way nondescript place that rarely makes it onscreen. It’s a town dominated by large industrial buildings, cars, parking lots, and run-down houses. Unlike Zhao, Riegel doesn’t try to find anything beautiful in the landscape, nor does she create beauty with her cinematography or lighting. Riegel’s camera stays close to her characters, observing their work in the scrapyard and the factory, giving it, at times, a documentary feel. Several scenes are shot at night, when the crew is illegally gutting buildings. Faces are illuminated intermittently by the lights of a passing car or a cigarette lighter. The color palette, which is established in the first scene, is a muddle of grays, browns, and dark blues, with Ruth’s hat and Blaze’s red truck standing out as the only touches of color in the scene.

This is a movie with immediately high stakes and a lot of action. Almost everything I have described so far occurs in the first ten minutes and the tension only mounts as Ruth and Blaze become more involved in the world of illegal scrapping. The work is exciting and the rewards are higher than they imagined, but so are the physical dangers—it’s not only the risk inherent in tearing apart old buildings but threats from other scrapping crews that compete with them for saleable materials. They also find that the man who hired them, Hark (Austin Amelio) has more of a crime boss’s mentality than they initially realized, making it difficult for them to leave the work behind when they’ve had enough.

There is a mood of desperation throughout, but it’s not a hopeless story or even particularly sad, perhaps because it centers on a young person with so much spit and vinegar. Jessica Barden, who I had already admired in the TV series, End of the F***ing World, is a magnetic young actor. She has a slightly raspy voice and a petite frame that bring to mind a young Holly Hunter. When Ruth is angry, her light blue eyes seem to go translucent. Her light-hearted side comes out when she and Blaze bicker like the siblings that they are. Gus Halper gives Blaze a boyish sweetness and optimism that makes you believe in his hopes for Ruth, but there are moments when he lets his guard down and you see how tired and anxious he really is, deep down. Holler is at its best, and most emotional, when it shows us how close Ruth and Blaze are and the risks they’ll take for each other. Ruth’s biggest leap of faith, it turns out, is to trust that her brother means it when he says he wants her to leave him.

Hannah Gersen is the author of Home Field and a staff writer at The Millions. She writes about movies on her blog, thelmaandalice.com, and @thelmaandalice.