Yesterday, June 20th, marked the official first day of summer! Though the longest day of 2024 has come and gone, the season still promises a plethora of long afternoons and lazy nights. Many of us at The Common cherish this time as an opportunity to comb through our bookshelves and catch up on our neglected To Be Read lists. In this edition of Friday Reads, our editors and contributors share what they’re reading this summer, with recommendations in an array of genres and topics fit for the park, a road trip, a cool refuge from the heat, or whatever other adventures the season may have in store. Keep reading to hear from John Hennessy, Emily Everett, and Matthew Lippman!

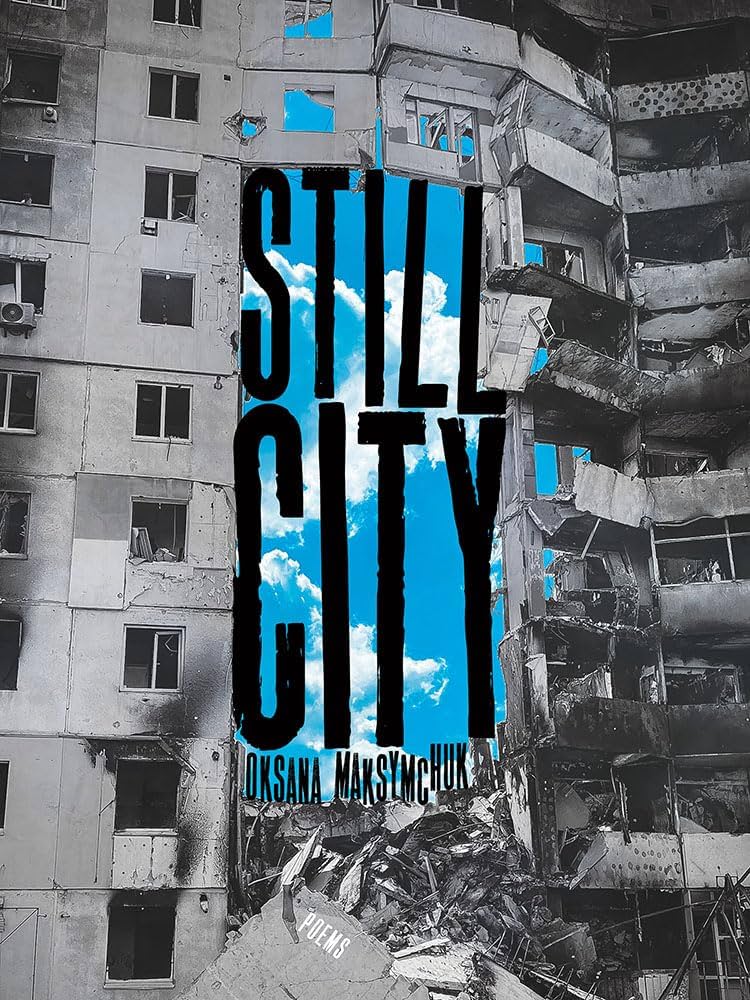

Oksana Maksymchuk’s Still City; recommended by Poetry Editor John Hennessy

I’m personally grateful for Oksana Maksymchuk’s new collection, Still City, a panoramic view of the Russian war on Ukraine, because we had the honor of publishing work from it in The Common. I also thank her on behalf of Anglophone readers for writing it, as it offers us—in English—a variety of voices from and perspectives on the civilian experience of war. Still City presents page after page of devastating emotional turns and sensory images—finger traps as well as landmines—in astonishingly good poem after astonishingly good poem. The last ten or so are among the most powerful poems I’ve read in ages, if comparisons are even apt. Any single one of them would have made a strong ending to the book, but this ends like the finale of a fireworks display—again, maybe a bad comparison, and we all know what those firework displays on the fourth of July imply and reference. At some point I started noting my very favorite poems, but the list is now over a dozen and nearly made moot by its length. I strongly recommend this book for its humanity and emotional resonance, as well as its clarity on the psychological and physical sufferings of civilians during wartime.

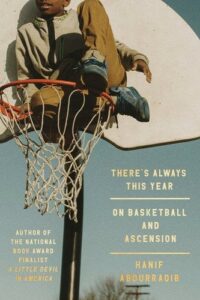

Hanif Abdurraqib’s There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension; Issue 27 contributor Matthew Lippman

Ball. Barbershops. LeBron. This is the water fountain at the park of There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension, the new book—memoir, social commentary, personal narrative—by Hanif Abdurraqib. When you look at the internal flap, his bio reads, Hanif Abdurraqib is poet…..That’s the first thing he wants the world to know about him or his publisher or the person making the decisions about Abdurarqib’s public persona. He’s a Poet. All ball. Barbershops. LeBron. Abdurraqib braids the braid of this this book to make ascension something to devour. The language goes up. It rises then holds for a second before dropping in the net. Swoosh. He’s a brilliant writer, and this is a brilliant book. There’s Always This Year…, writing backwards in time, each section counting down towards zero, how he moves from his brother cutting his hair to the shape of the orange Spalding rock into the political artistry of LeBron and high school basketball in Columbus, Ohio, late ’90s. It’s all poetry. This is the beauty of the book—it steams up from the blacktop in poetry towards silence, some mythical, mysterious quiet that is the most necessary element to being a poet. He writes, But one thing I would crave is the silence. The emptiness of it all. In the spring of 2020, when I thought the world was doing a dress rehearsal for the apocalypse, the only thing that comforted me was the silence. Knowing that the city would otherwise be flooded with shouts and sounds and yet was forced to restrain itself was strangely calming for me. Barbershops. LeBron. Ball. This book is all of it. It’s that moment when the basketball almost stops to admire itself in midair—where it came from and where it is going in arc of its ascension, in that quiet moment—and then it drops, the rock in the hole, all net, the thrill of the swish.

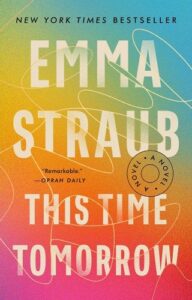

Emma Straub’s This Time Tomorrow; recommended by Managing Editor Emily Everett

After a long dry spell, I went on a real reading bender last month. The books I’ve been reading all seem to drive forward with twisty plots, convoluted conspiracies, and elaborate set pieces. It’s propulsive, of course, but sometimes it feels like being a marionette—like being dragged along by my strings through each new dramatic sequence. The problem with constantly ratcheting up tension is that it can be hard to pull it all together into something truly, fundamentally satisfying.

Emma Straub’s This Time Tomorrow does have a pretty dramatic premise; drunk on her fortieth birthday, Alice accidentally time-travels back to her sixteenth birthday. But I was hooked long before that happened. Straub’s prose is so funny and smart, so perfectly pitched, that I would have devoured this book even if Alice’s days consisted only of going to work at the fancy private school she once attended, and visiting her slowly dying father in the hospital, which is pretty much the lay of the land before the birthday incident. If that sounds depressing, it’s not. The narrative voice, a close third, is irresistibly Alice: wry, sensible, searching. Even waking up to her lean, ache-free, sixteen-year-old body—and her young and healthy father eating Grape-Nuts at the breakfast table—doesn’t throw the story into unmanageable chaos. Alice goes to the SAT-prep class like she’s meant to, wondering how long this will last, thinking of the birthday dinner she’ll have with her dad and best friend, the long lost crush she’ll see at her birthday party. But of course, going back makes Alice question everything about her present: how she ended up single and childless, how her father ended up in a hospital bed long before his time.

Beautiful and sad and joyful, This Time Tomorrow isn’t un-put-downable because of its Back to the Future plot twist; it doesn’t need to raise the stakes ever higher to keep you reading. The stakes are life—will we make it, will we do it right? Can it be done right, ever, even if you can do it all again?