Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

The long New England winter is finally thawing, and here at The Common, we’re gearing up to launch our newest print issue! Issue 29 is full of poetry and prose by both familiar and new TC contributors, and a colorful, multimedia portfolio from Amman, Jordan. To tide you over, Issue 29 contributors DAVID LEHMAN and NATHANIEL PERRY share some of their recent inspirations, and ABBIE KIEFER recommends a poetry collection full of the spirit of spring.

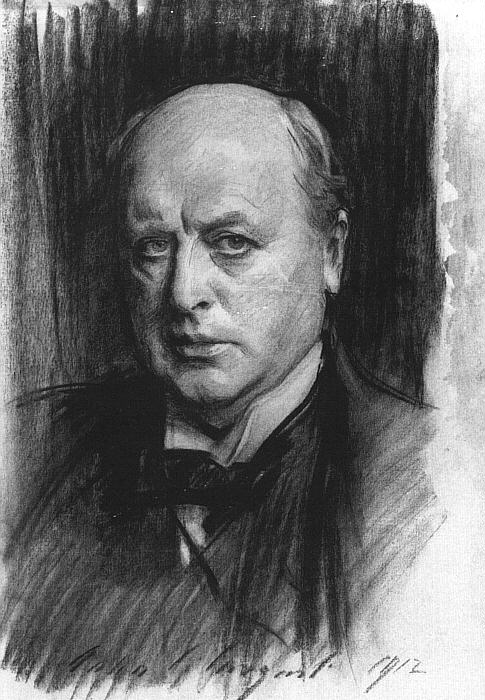

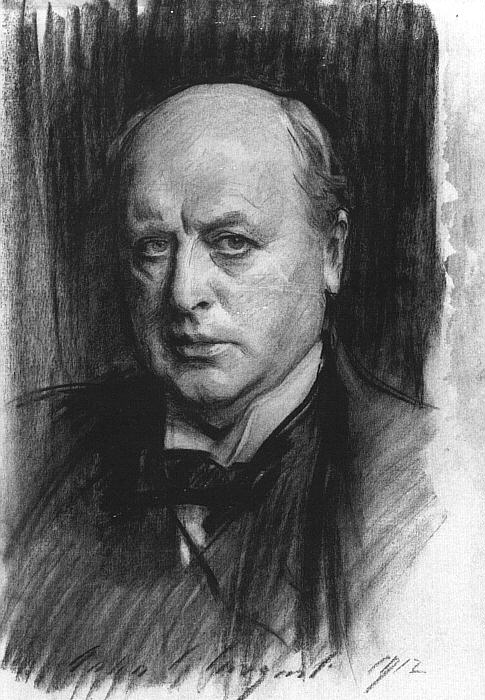

Henry James’ short works; recommended by Issue 29 contributor David Lehman

I’ve been reading or rereading Henry James’s stories about writers and artists: “The Real Thing,” “The Lesson the Master,” “The Death of the Lion,” “The Tree of Knowledge,” “The Figure in the Carpet,” “The Aspern Papers,” et al. His sentences are labyrinthine, and you soon realize how little happens in a story; the ratio of verbiage to action is as high as the price-earnings ratio of a high-flying semiconductor firm. Yet we keep reading, not only for the syntactical journey but for the author’s subtle understanding of the artist’s psyche—and the thousand natural and artificial shocks that flesh and brain are heir to.