Text by JOCELYN EDENS

Art led by TATIANA POTTS

The Gathering

To fold is a verb, a gesture. It’s a familiar one. Think of folding a loose piece of paper to fit in a notebook, or dogearing a book to hold your place (even, with some holdout skeuomorphic designs, on some e-readers), or of bodies folding to reach the ground. It’s a gesture that practice improves. With time and repetition, edges might line up more neatly, creases might become sharper. The fold itself is a trace of that gesture and practice. Depending on the weave and thickness of the paper, and the pressure exerted on it, a fold might contain a strong or weak memory of that gesture—it might be inclined to hold on to a fold, or to forget the gesture and bend back open.

During the frigid second week of January 2018, six people gathered in Amherst, Massachusetts to fold and paste together a three-dimensional paper architecture. Equipped with piles of printed paper, a handful of bone folders and utility knives, cutting mats, and a couple of pints of glue, we turned the Mead Art Museum’s William Green Study Room into a temporary artists’ studio, headquarters for a new Hall Walls installation, part of an annual project that gives visiting artists and students the freedom to create an ephemeral mural on the museum’s walls.

In this iteration of the project, artist Tatiana Potts and I worked with students Stephen Johnson (Amherst College ’19), Effy Yao (Mount Holyoke College), Gina Pryciak (Skidmore College), and Marley Nascimento (Greenfield Community College/Amherst Pelham Regional High School), as well as Study Room Manager and European-Print Specialist Mila Hruba, to construct an architectural world both new and familiar.

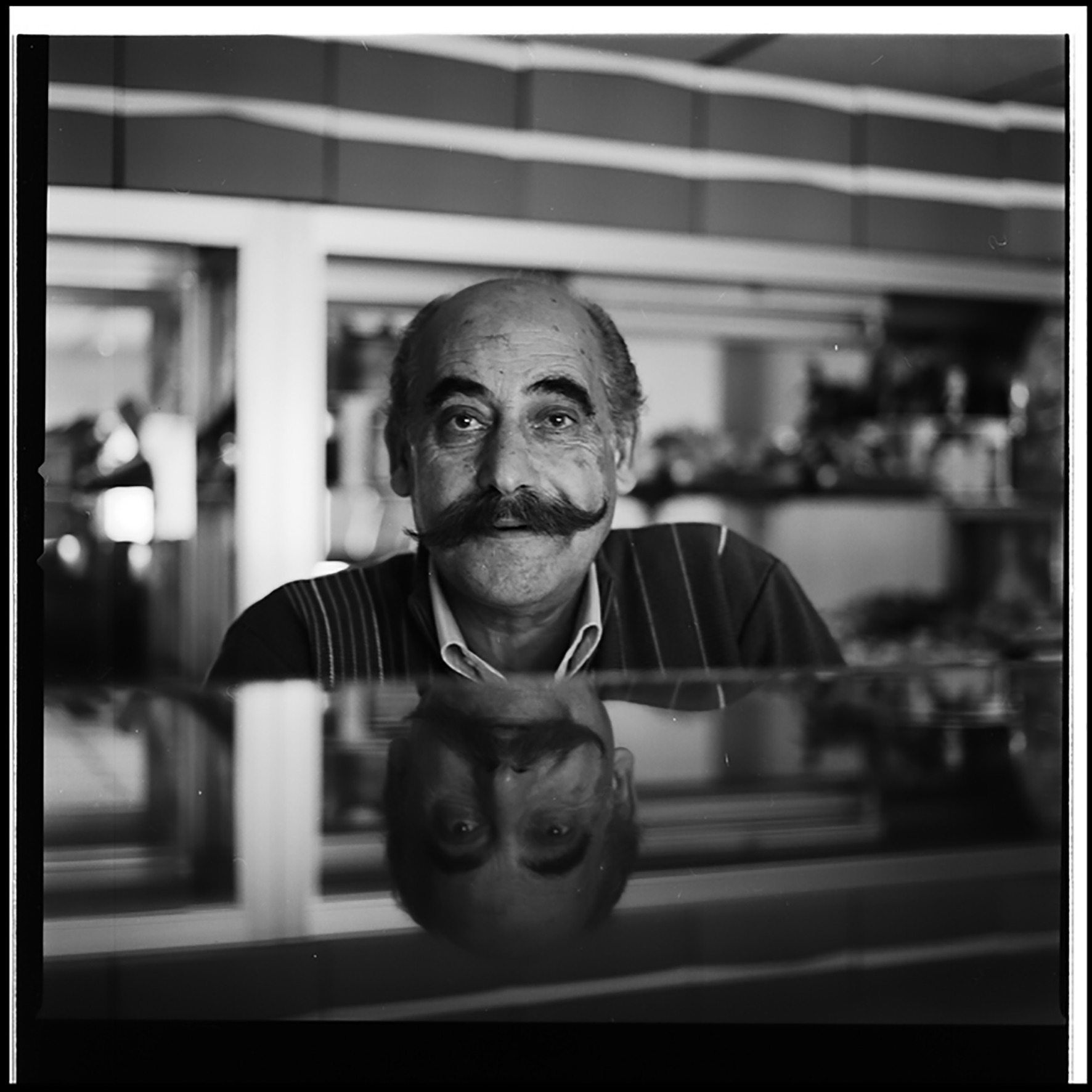

Potts, who is a printmaker and bookmaker, works with paper, an everyday kind of material that is both flexible and durable. Born in Slovakia to a mother who worked as a photographer for a newspaper, Potts grew up among printing presses and the smell of ink. Travel is a big part of Potts’s story—from Slovakia to England, Spain, the United States. After she moved to the U.S. in 2000 and lived for a time in South Carolina, North Carolina, then Tennessee, Potts noticed an architectural logic that scholar and architect Keller Easterling might call subtraction: a tendency to make new buildings by subtracting old ones, an economy in which large tracts of land get unbuilt and rebuilt.[1] This contrasted with the slower architectural shifts Potts had experienced at home in Slovakia. While new buildings pop up and down like whack-a-moles in the U.S., Potts could return home after being away for years and find Slovakia’s built environment largely unchanged. There might be new additions, or some changes in color or shape, but rarely did urban planners make room for brand new buildings by subtracting, detonating, or tearing down; the overall architectural skeleton of the place remained much the same.

These observations led Potts to experiment in her work with temporary paper architectures, sculptural forms constructed to create the illusion of outlines and shapes from neoclassical Euro-American built environments. The three-dimensional forms that Potts has made since 2016 are vaguely familiar. Though fictional, we might already remember this place. Attuned to small architectural details, Potts uses brick work, keystones, thresholds, iron ornaments, and the like as inspiration for her new, large-scale environments: printed, popped-out works that can take up the whole of a fourteen-foot wall. Potts’s paper forms are surprisingly durable. Folds stay crisp, colors remain bright. They are, however, impermanent; the modular components of one environment might be subtracted and repurposed for another.

Potts came to the Mead with these experiments in mind. She began her work here with some preliminary sketches based on fragments of architectural motifs at Amherst College (especially one window of Morris Pratt Dormitory) and lists of word associations related to buildings, place, and memory in the context of campus architecture. She arrived at our January gathering with supplies, a plan, and every expectation of deviating from that plan.

In my experience, printmakers tend to share a culture of co-learning. Working in a mode of making preoccupied by process—all the ways to make a mark, to apply ink to a surface, to manipulate the weave and texture of paper—the printmakers I’ve worked with tend toward an obsession with skill-sharing and gift-giving. Tatiana Potts creates with this kind of generosity. Potts came to the Mead with her paper already printed, and so the skills Potts shared with us focused on the next steps in her process: the fold (turning two dimensions into three) and adjusting to the realities of a site-specific installation, in which you can’t change the dimensions of the space or the location of the fire extinguisher or the laws of gravity.

We might call this “learning by doing,” not a particularly new idea, but a good one. In Democracy and Education (1916), philosopher and educational reformer John Dewey described learning by doing as active, involving the whole body and the hands especially, a convergence of subject matter with action and practice according to the inclinations and commitments of the person doing the doing. Learning by doing offers a material intimacy with and knowing of things in the world, “act[ing] with or upon the thing so frequently that we can anticipate how it will act and react—such is the meaning of familiar acquaintance. We are ready for a familiar thing; it does not catch us napping, or play unexpected tricks with us. This attitude carries with it a sense of congeniality or friendliness, of ease and illumination…”[2]

The Fold

Tatiana Potts makes her three-dimensional paper architecture through a series of folds. The design that Potts prints on her flat paper gives each finished installation its color; its geometric lines act as guides for folding. Potts’s instructions were relatively simple: take a straight edge and score (crease) along the lines of the design, fold, and pop the paper into ridges and valleys. Clever is the artist who eliminates the need for constant measuring.

We didn’t count along the way, but a retrospective count suggests that together we made close to 9,600 folds in five days to prepare this installation. That is to say, we became rather intimately acquainted with this particular fold pattern: hands remembering precisely what they’re supposed to do free the brain to focus on other things. Paper folding, it turns out, is a sister to a sewing circle. As we got to know each other, we swapped book and podcast recommendations and shared music that had recently hooked us. What I remember: listening to H.E.R. for the first time, hearing Questlove and Black Thought describe the writing process for “It Ain’t Fair” on the podcast Song Exploder, and, by some serendipitous accident, listening to a cover of the Bee Gees song “Massachusetts” by Czech singer Václav Neckář. The Bee Gees wrote the song in 1967 without ever having been to Massachusetts but liking the name. One year later, hippie resistors in Liberec, Czechoslovakia sang the song while taking down the city’s street signs to make driving a pain for Russian Soviets; Neckář recorded his Czech version that year. All these details appear to be unrelated and coincidental, evidence of a place (or the constructed memory of a place not yet visited) moving through the world according to the flows of top song charts and global geopolitics. These were some of the soundtracks to our folding.

The Attachment

When we folded, we did so in strips: long paper pieces, with some segments popped into three dimensions and some kept flat. The next step was to line up these strips to build an architectural shape—an arch, a doorway, a column—and attach them to a broad, plain piece of paper. We then attached these modules to the wall. Glue, velcro, and magnets held this thing together and upright. This is the part where we became acquainted with how gravity and several layers of heavy paper get on together.

Once the pieces became one form, the screen-printed ink started to create optical illusions. The difference between ink and paper, in color and texture, giving this paper architecture an appearance of mass and volume that far exceeded its actual heft.

Depending on where you’ve spent time in your life, Potts’s paper architecture in Hall Walls might seem familiar. Doors, arches, and columns are rather consistent architectural tropes. We like our thresholds. Walking by the installation, white shifts to yellow, black to blue; it’s like watching the facade of a building change with the direct, then glowing light at sunset. Even a constructed, fictional environment can activate memories.

Jocelyn Edens is an educator at the Mead Art Museum at Amherst College. She is also a curator of projects with contemporary artists.

Tatiana Potts works with printmaking and paper sculpture to construct new architectural worlds. Originally from Slovakia and currently based in Knoxville, Tennessee, Potts is associated with the University of Tennessee School of Art and has work in the collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum and the National Taiwan Museum of Fine Arts.

[1] Keller Easterling, Critical Spatial Practice 4: Subtraction, Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2014.

[2] John Dewey, Democracy and Education, Project Gutenberg EBook, released July 26, 2008, last updated August 1, 2015. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/852/852-h/852-h.htm