TYLER BARTON interviews ANANDA LIMA

Sometimes I forget what a chapbook is for. Sometimes I think it’s the demo tape that hopes to precede the real album. Sometimes I think it’s the resting place for early work, work often promising, but ultimately unfinished.

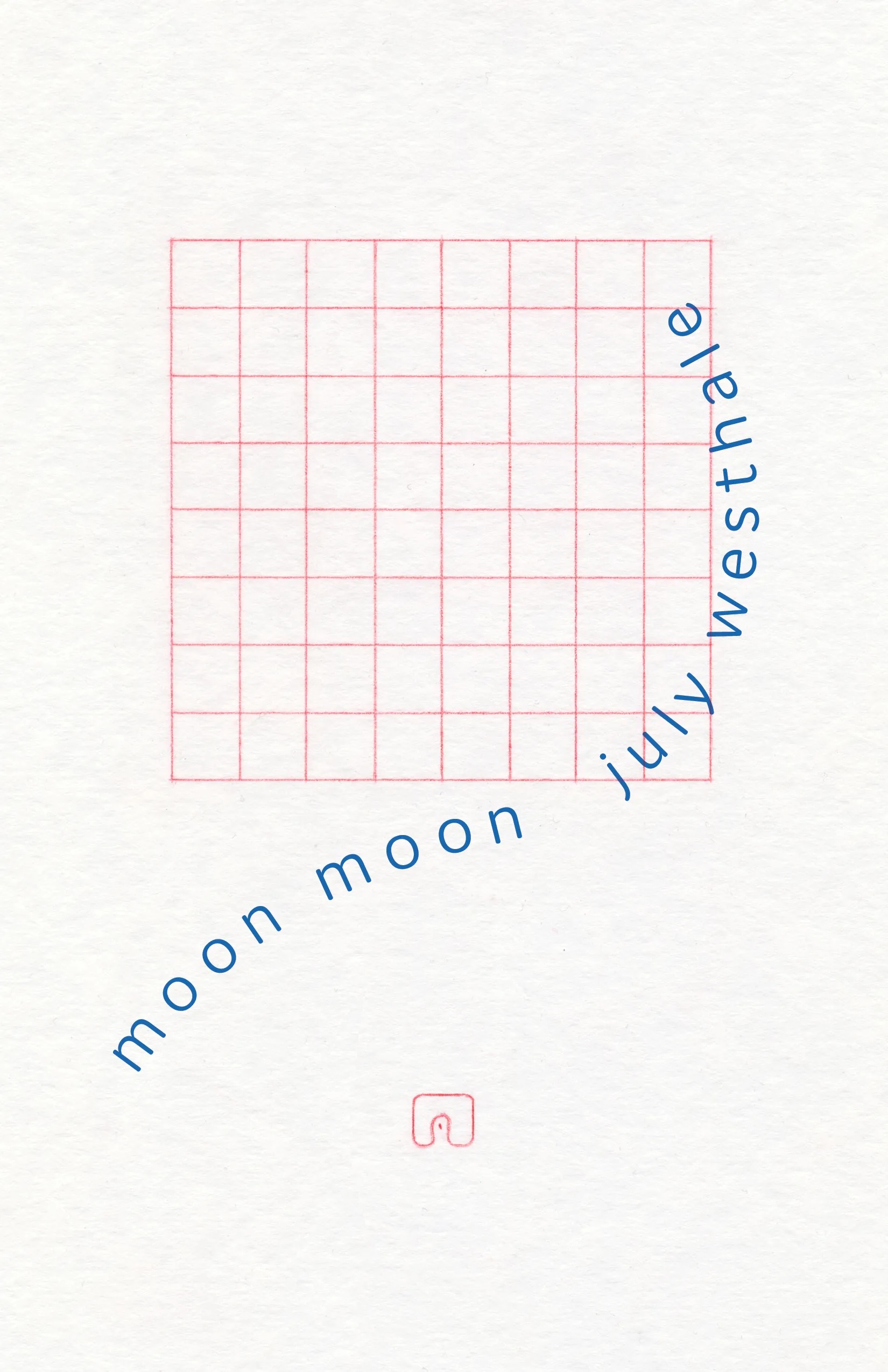

Thankfully, I’m sometimes reminded, as I was by Ananda Lima’s Amblyopia (Bull City Press), that chapbooks are a space for focused and fully realized projects, projects that describe a writer’s growth into a new voice, form, style, or focus. Amblyopia is an 18-page experiment that contains 13 miniature experiments, each unique in form or style, though all solidly linked to four woven thematic threads—photography, disability, motherhood, and the ineffability of language itself. (It figures that the last two times I felt this strongly about a chapbook were also Bull City Press’s Inch Series chapbooks—Alina Stefanescu’s playful Ribald and Rose McLarney’s gorgeous In The Gem Mine Capital of the World.)

Amblyopia is an eye disorder in which the brain begins to favor one eye over the other. Though Lima suffers from the disorder only mildly, it was witnessing her son’s more severe battle with amblyopia that, in conjunction with her interest in bilingual poetics, compelled Lima to create the experiments that became this moving and innovative chapbook.

From the first poem, which stretches and fades (literally) from English into Portuguese, it is clear there is something special about this book; but as I read, each succeeding poem continued to surprise and (beautifully) befuddle me. I read them all twice, then again before talking with Ananda Lima, and I’m reading them again tonight as I reflect on the conversation we had in January.

Tyler Barton (TB): Given that the cover features a double-exposure photograph you took, and the pages include poems like “Dark Room” and “Photograph of water as a mass noun,” this chapbook seems to be as much about photography as it is about amblyopia. I found myself making a narrative connection between the two. Did your experience with amblyopia compel you towards photography?

Ananda Lima (AL): I am so happy that this is the first question. Sometimes the other themes in Amblyopia (e.g., amblyopia itself, the mother-son relationship, language) come to the forefront and obscure the photography theme.

For a long time I wondered about the effect my mild myopia had on my photography. Because my vision conditions are much milder than my son’s, I could always get by. When I was younger, I most often walked around without glasses, which meant that the world felt far away and always fuzzy. That presented challenges, but also had a lovely side to it—things that weren’t right in front of me acquired this dreamlike quality.

As a photographer, I always tended toward the close shots—details first. I think this is something that affected my sensibility and interests in photography, as well as my writing, and my life in general. When I started investigating the challenges my son has with vision, I started thinking again, more purposefully, about all of the effects this has on both of us, and in my work.

TB: Was taking photographs something you did before you came to poetry? Did it somehow lead you to poetry?

AL: I started taking pictures as a child when a relative who lived in the US gave me their old camera. I have loved it ever since. But it started as nothing very intentional, just regular family pictures, birthdays, etc. I think the photography side developed more openly. People knew for a long time that it was a thing for me, yet my writing was very private. In my twenties, I did more intentional work as a photographer. I joined a couple of loose collectives in New York City when I moved there, and eventually I showed some of the work. I worked with photography on the side too, mostly doing weddings, to make some money to get all my photography gear. So I, and my friends, thought of me as a photographer.

Writing was much more private. However, when I started to show my writing to other people and pursue it more seriously, it sort of took over. I could never let go of photography, but I think writing is my primary medium.

TB: On the subject of art and writing, can you talk a bit about your approach to ekphrasis? A number of these poems are inspired/informed by other works, such as George Oppen’s poem, “A Theological Definition.” Do you set out to write about another piece of art or do these things ‘find their way’ into what you’re already writing?

AL: As a reader, I love ekphrastic work—poetry, prose, anything. People approach it in such varied, smart, and interesting ways. For me, I rarely set out to do it. The way it usually happens is that works of art (often other poems or songs, but also visual work) provoke such a reaction in me that I find myself writing about them. It is a little different from non-ekphrastic poems in that objects of art come with their own language that has been constructed by the artist. In the case of other poems and songs, those may involve words. So there is this layer of experiencing that language, as well as thinking of the artist who created it. It can be the experience of experiencing someone else’s experience.

As a subset of my interest in ekphrastic work (both as a reader and as a writer), I am very interested in experiences of art that are not learned. That is, when the person experiencing it doesn’t know everything about history, technique, etc. I am fascinated by that. I was born and grew up in Brasilia, and I love the architecture there. It is very present and prominent in the city. I didn’t know anything about architecture in a theoretical sense or what was behind it all intellectually, but I and many many people around me just lived it, experienced it. I am interested in how writers convey their experience of a piece of art outside of a theoretical understanding of it.

TB: I was struck immediately by a number of formal ‘experiments’ in the chapbook. The first poem, “Amblyopia 1,” sort of pulls apart into Portuguese, correct? And “Candling” loosely adapts the pantoum form.

AL: Before this project, I had been working with Portuguese and English within single poems. I was very interested in how I could make the poem feel like a single unit or two discrete units in tension within the poem. I was thinking about translation, access, and how to make the two languages not just say the same thing, but add to each other. I had been playing with repeating forms, especially the pantoum, so that instead of repetition, I would have translations and re-translations. I was embracing all the challenges of translation (e.g., syntax and mismatched line breaks, homophones, etc.) and made them a source of creation and difference, a divergence between the languages. I was having a lot of fun with that.

When I encountered the subject of amblyopia in my life again, I was amazed at how well it fit into the work I was experimenting with already. There was this very intense period of my life when I found a specialist that explained amblyopia to us. He was describing my son and I thought: “Wait, isn’t everyone like that?” And then I began to realize that these things I thought were just quirks of my personality (e.g., difficulties with spatial processing), were actually the result of amblyopia. All the difficulties the doctor was describing in my son, I recognized in myself. I also felt an intense guilt at having passed my amblyopia on to him (though his experience is more severe). I was thinking about how my parents were not aware of my amblyopia and didn’t help me.

There was a lot going on: At the most basic level there are the two eyes; input from the weaker eye ends up being suppressed to favor input from the stronger eye. This fit very well with the work I had been doing with bilingual poems, especially if you begin to consider the homophone “I” (an English “I” and the Portuguese “I”). The two languages within a poem worked to mirror some of the effects of amblyopia as well. With amblyopia the brain can fluctuate between seeing the input of both eyes as an integrated single image (as it usually occurs in binocular vision) and having two competing images that are not properly integrated into a unit. In our case this made things blurry, but it can also make people see a double, ghost-like image. I was amazed at how it paralleled the bilingual work I was doing. There were also the words “left” and “right” which were repeated constantly when talking about amblyopia (to refer to the eyes but also because amblyopia interferes with the ability to tell right from left). That also spoke to me, as I was at the time living in the US and following what was happening in Brazil, with two horrifically extreme right-wing presidents. For example, it made me think of close family members I cut contact with because of their extreme right-wing values, and the still very recent history of a right-wing military coup in Brazil, and their terrible crimes suppressing dissidents, which of course often included those on the left.

It was all so obviously poetic. The two eyes mirrored what I was working on already, with these two languages sort of fighting in my poems. The experimentation in my work came from all of these things coming together. It was a huge relief to me when I wrote that first poem. It gave me a way to get a handle on what was going on. I needed the container of the formal experimentation.

TB: And then there’s my favorite piece, “Hart Chart”, which is structured like a word search but also calls to mind an eye/vision chart.

AL: I wrote “Hart Chart” when I was working daily with my son on exercises for his eyes. It was tough on both of us. One of the exercises involved a Hart Chart, which is used to train the eye to find and keep its place. Again, the language we used helped the poem. He had a chart close to him and I held another far away. He would have to say the first letter on his chart and then the one in my chart on the same position, e.g., “A for me, G for you.” One day he said “U for me, I for you” and I knew that it was going to be a poem. I was writing loose sonnets, so I made it 14 lines of 14 letters. It was a lot of fun.

TB: That’s so beautiful. Especially because that final line of “Hart Chart” is kind of hard to crack at first. As a reader, I really had to work to decipher what is being said, even on a literal level. I was like, “Is there something here I’m not seeing? Something I’m not seeing in the right way?”

AL: I love hearing that it was hard to crack that poem at first, and that you stuck with it. Because part of what I have been interested in with the translation/bilingual poems is how to work with the fact that readers will not ‘get’ everything in the poem. Form gave me a helpful framework to help the reader who doesn’t speak both languages a little bit, but it doesn’t make everything clear. I think a lot about this. As a reader, I am very comfortable and actually enjoy not getting everything in a poem, story, or even conversation. I like looking up things. I like wondering. I like the feeling that there is something to be discovered. I remember fondly the pleasure of hearing English when I was first learning (a long time ago now). There is a point when you understand the gist of it fairly well, yet if you stop to look at individual words, you lose it. It was like magic, and it required a level of surrender. When my English improved, I remember getting that feeling again at a Shakespeare-in-the-Park type event. I understood the story and what was going on, but had trouble being aware of the meaning of individual words. It was wonderful. To understand it, I had to let go of control and surrender to the language. But it wasn’t just language. I am good with the language now, but there are also cultural references, especially of specific periods when I wasn’t here. TV ads, famous events, things like that. Part of my tolerance (and embracing) of not getting everything all the time comes from moving between countries, groups, circles, and therefore missing both high culture and everyday American pop cultural references. Part of it is that things are not catered to me. I also think this tolerance may be related to the vision thing I was describing earlier when talking about photography, finding the joy of having part of the scene blurred. In this project I worked on letting some of that experience be there for the reader, some places where the meaning might not be immediately available.

TB: I love how Amblyopia ends on the idea of revelation. I feel as though I learned a lot from reading this book (about amblyopia, about saccades, about Portuguese, even George Oppen) and had many moments of revelation (which have only continued to occur for me during this conversation). Can you talk about a revelation you had since finishing this book? Did writing it teach you something?

AL: I was learning so much as I was writing this book. There were so many things that were conceptually interesting, but it had such a weird quality because I was learning them for important practical purposes and needed to apply them. I contrast that learning with learning interesting things at a class or for pleasure reading. The urgency made the moment of learning so different. The poems gave me some space to marvel at it all outside of the moment in which I was battling with the effects of my son’s amblyopia. It allowed me to pause and have that intellectual pleasure of learning. I could experience the language and the poetic side of the whole drama.

I love that you brought up that ‘revelation’ in asking this question. It is so fitting. There is a pleasure I get thinking about that moment where a photograph is developed and the image starts to emerge on the paper. It is such a simple yet beautiful moment. I felt a similar pleasure in noticing that the word in Portuguese for developing a photograph is revelation. Writing these poems gave me the space to allow myself similar types of appreciation for what we were going through.

*

Amblyopia by Ananda Lima is available now from Bull City Press.

*

Ananda Lima’s poetry collection Mother/land was the winner of the 2020 Hudson Prize and is forthcoming in 2021 (Black Lawrence Press). She is also the author of the chapbooks Translation (Paper Nautilus, 2019, winner of the Vella Chapbook Prize), Tropicália (Newfound, forthcoming in 2021 winner of the Newfound Prose Prize), and Amblyopia (Bull City Press – INCH series, 2020). Her work has appeared or is upcoming in The American Poetry Review, Poets.org, Kenyon Review Online, Gulf Coast, Sixth Finch, The Common, Poet Lore, Poetry Northwest, The Cortland Review, Colorado Review, and elsewhere. She has served as the poetry judge for the AWP Kurt Brown Prize, as staff at the Sewanee Writers Conference, and as a mentor at the New York Foundation for the Arts (NYFA) Immigrant Artist Program. She has an MA in linguistics from UCLA and an MFA in creative writing in fiction from Rutgers University, Newark.

*

Tyler Barton is a literary advocate and cofounder of Fear No Lit. He’s the author of the story collection, Eternal Night at the Nature Museum (Sarabande, 2021) and the flash chapbook, The Quiet Part Loud (Split/Lip, 2019). Find his fiction forthcoming in The Adroit Journal, DIAGRAM, Copper Nickel, and The Common. Find him at @goftyler, tsbarton.com, or in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.