By SUPHIL LEE PARK, RICHIE HOFMANN, KAREN SKOLFIELD, CLIFF FORSHAW, T.J MCLEMORE

Contents:

Suphil Lee Park | Hua Tou

Richie Hofmann | City of Violent Wind

Karen Skolfield | Gettsyburg Relics for Sale

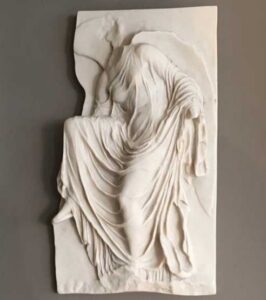

Cliff Forshaw | Parthenon Bas-Relief

T.J. McLemore | Sunday, October 23, 4004 BCE

Hua Tou

By Suphil Lee Park

The syntax of youth is to age

unfazed. Young, big statements

mistake a period for the beginning

of ellipsis I vowed against…

Based on one sentiment

I’ve desired—I want you

at an insurmountable distance

for my life to go on

towards you. A stretch of despite

and because to swim across

lies between any two of us.

It all comes down to the turf

fight of second thoughts.

Each word, yet to define its renewed

reality, is ever day-old.

Death awaits in my childhood

cat’s grave, and the idea of home

is an index thinking up the first draft

of a book to house it.

Despite the desperation of nouns,

articles celebrate. Because the pain is a pain

just as a pain is the pain.

A daily sequence of sunlight is all it takes.

Even the darkest night.

Even the end of it.

City of Violent Wind

By Richie Hofmann

I

Heavy shutters

on the windows. A fresh nudity

in the sky, to the south, the east—

It is the wind that once threw

my high school French teacher

from her bike, headfirst into a wall.

Madame opened her eyes: a crucifix,

her two hands bandaged.

Nurses circled her bed in white habits.

Her glasses were gone.

She was American, the air smelled,

the floor was stone. She understood so little

of what the nurses said in their Southern accents,

asking her

if she was hungry.

II

—I looked down and saw his hands

moving above the keys

while the arpeggios tripped over themselves (Ravel??)

six floors up from the medieval street.

Mars shone:

a bright dot.

No longer like wind, but water,

the relationship between the piano and the sound of water,

orderly,

and yet

tenuous, volatile.

We saw Lortie do it in Chicago.

All technique, no passion, a critic said, but that was what I liked.

In Avignon, I watched hands

crossing one over the other.

Then a student or girlfriend

came and sat next to him on the bench

and he kept playing.

III

The window sucking in the curtains,

the earthenware pot filled with thistles.

My t-shirt up to my chin, the wind blowing tissues from the bed—

You on your bicycle ahead of me, sweat—

The hares hid when we rode past—

Pollarded trees with gnarled stumps

which men hung their straw hats on—

The abandoned hut with the bashed in roof

where we didn’t suck each other—

The room aristocratic

but faded,

two antique twin beds pushed together.

IV

The churches darkened.

The shutters latched.

The season of the end

of desire (Petrarch

met Laura here). A dog slumps

down, his owner is an old woman holding a glove

to her lips—

I imagine for a moment that the love

she gave her life to

is buried in that abbey of stone.

City of violent wind, but no wind.

Students drink by the wall,

the bars are open

and play American music.

Gettysburg Relics for Sale

By Karen Skolfield

Before the National Park you’d take souvenirs

if the farmer said okay, carve Minié balls

from living trees or from the dead.

Stumps with their secret bullets

or plowed into the earth like seeds.

Relic from the Latin for remains

of a martyr, believed even after death

to perform miracles, the ungnarled hands,

the lame leaping with joy, the leprous skin

brown and whole again. Also from

relinquere, to leave behind: spent cases,

a rifle jammed, so many bodies

at Gettysburg that one rocky section

earned the nickname Devil’s Den, another,

Slaughter Pen. High ground, that tactical,

terrible advantage. The deception

of Gettysburg: rolling hills, mostly,

the grade so slight that tourists with canes

may tick their way on up. We walk,

glad for the leg stretch after hours

in the car, a clean November chill.

Authentic, declares a roadside stand.

Legal, says another. In a glass

by the cash register, a mix

of thin Confederate and Union flags.

No sign on these except the price

which we agree, too high.

Parthenon Bas-Relief

By Cliff Forshaw

after “Celle qui passe: Bas-relief du Parthénon” by Gérard d’Houville, (1875-1963), pseudonym of Marie de Régnier, née Marie Louise Antoinette de Heredia. The bas-relief is Nike Adjusting her Sandal (c. 410 BCE), a fragment from the Temple of Athena Nike at the Acropolis. The sculpture is damaged and Nike, winged goddess of victory, has no face.

- The Passer-by

An age away you stopped to tie your lace.

What was your name? Who traced your frozen charm?

Your body’s with us still: you have no face.

Was it soft, or haughty? Tender, fearful, calm?

We’ll never know if it equalled the way your stance

tips a half-cradled breast from your folded arm.

Forever you twist to retie your sandal, balanced,

one foot in air, gathering up your train,

a fugitive caught in a pale marble trance.

Where are you from? Which god awaits in vain?

You can no longer hurry on. You remain

here, beyond all happiness and pain.

You were so ready, always already gone.

You rest alert, eyes neither open nor shut,

sleep rippling through your tunic of diaphanous stone.

Time to let go that cloth’s now useless knot.

One arrives too soon among the Shades.

Your headstone’s dressed: your dates already cut.

Heading to Hades or the sexton’s spade,

why bother, girl, to up your game, unfreeze?

That sculptor saw your body open wide

and caught it hinged on the springs of your young knees

Listen! Just stay like that. Old age, disease,

they lie in wait. These things and more besides.

Best now to pause, now everything’s in place.

Death will surely come. I know. I know.

No longer any need to see your face.

I think… I think… I think it looks like Grace.

- Nike Tying Her Sandal

Minutes or millennia later, she’s all wound up,

crouched to check her laces. Tick.

Fits spikes to block, coiled and ready.

Gone. Already, long, long gone.

Cracked her getaway, left us,

with the dying echo from the gun.

Sunday, October 23, 4004 BCE

By T. J. McLemore

God made the world, we’re told,

to be known to us. To transform chaos

into law. In a puff of cosmic smoke—

a rabbit pulled from a bottomless

black hat—he blinked the globe

faithfully into its appointed place

to fill the blankness of the surrounding

space and stars in all its perfect

(so unchanging) glory. Bishop Ussher

calculated that the world began

on a Sunday in October, a universe complete

as the one who called it into being

with a few simple sentences. But it bears asking

what syllables did the trick back then

since our language has so much trouble

sitting still. Any Old English world-making

would’ve needed the wyrcan of working,

suggesting some sweat, a trace of

intransigence. The old German word

when God moved back and forth over the face

of the waters was ficken, which also gave us

to flicker and to fuck. Which is, after all,

how anything else gets made, thank god

for the God of love and the ferment of

the fecund waters. The great labor

of his making finally done, in the Dutch

God would’ve rusted on the seventh day.

And reclining he’d have managed to see

that this sculpted, still unfired world was good,

a word not related to our god. As we named

power without end, our mastery of

the Word remade us in its own image—

so when we call gutt, ghut, god

we mean that which we invoke,

the thing we created and called upon

to hear us as the silence fell.

Cliff Forshaw lives in Hull, UK. His collections include Vandemonian (Arc, 2013), Pilgrim Tongues (Wrecking Ball, 2015) and Satyr (Shoestring, 2017). He has been a Royal Literary Fund Fellow at York and Hull Universities, twice a Hawthornden Writing Fellow, and held residences in France, Kyrgizstan, Romania, Tasmania and at Djerrassi, California. He is also a painter. http://www.cliff-forshaw.co.uk/

Richie Hofmann is the author of a collection of poems, Second Empire (2015). He is currently Jones Lecturer in Poetry at Stanford University.

T. J. McLemore is the author of the chapbook Circle/Square(Autumn House, 2020). His work has appeared in New England Review, Crazyhorse, 32 Poems, Poetry Daily, Michigan Quarterly Review, SLICE, Adroit Journal, and other publications. His awards include the Autumn House Press Chapbook Prize, the Richard Peterson Poetry Prize, nominations for the Pushcart Prizes, and inclusion in Best New Poets. He has served as a Pinsky Teaching Fellow at Boston University, a Poetry by the Sea Scholar, and a Tennessee Williams Scholar at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference. McLemore is a PhD student in English Literature and Environmental Humanities at the University of Colorado Boulder.

Suphil Lee Park is the author of Present Tense Complex, winner of the Marystina Santiestevan Prize, forthcoming in 2021. She spent 9/14 of her life all over the Korean peninsula before landing in the American Northeast. She graduated from New York University with a BA in English and from the University of Texas at Austin with an MFA in Poetry. Her poems and short stories have appeared or are forthcoming in Catamaran Literary Reader, Colorado Review, Global Poetry Anthology, Image, Ploughshares, Quarterly West, the Iowa Review, and the Massachusetts Review, among many others. You can find more about her at: https://suphil-lee-park.com/

Karen Skolfield’s book Battle Dress (W. W. Norton) won the 2020 Massachusetts Book Award in poetry and the Barnard Women Poets Prize. Her book Frost in the Low Areas (Zone 3 Press) won the 2014 PEN New England Award in poetry. Skolfield is a U.S. Army veteran and teaches writing to engineers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. www.karenskolfield.com