By MERCÈ IBARZ

Translated by MARA FAYE LETHEM

Close, so close he can already taste it. This afternoon he’ll become the owner of a secret. But first he’ll have lunch with his mother, who’s waiting for him at the restaurant in the back of the Boqueria Market, and once he’s got her home safely, he’ll meet up with the current owner of a Picasso engraving and he’ll buy it. He has the cash in his wallet and enormous anticipation on his lips, which his mother will find disproportionate to the amount of money he’s about to spend on an emotional transaction that she links with his bachelorhood, with his lack of responsibilities and, to be perfectly frank, with some nights that are perhaps a bit too arid, she says as she places her wine glass down on the table with geometric precision and, satisfied, lights a cigarette.

“Too arid? You mean nights with no penetration?”

It took him a few seconds to choose the word, not as common as some of the others that had crossed his mind.

“Exactly.”

“Then why are you speaking as if you were Claudette Colbert…?”

“She’s not as famous as Picasso, but don’t think Colbert was a prude. Watch It Happened One Night and learn something; it’ll do you good. More than buying that smutty drawing. Let’s just say that movies used to have a moral, a happy ending.”

“That’s what I’m hoping for, that the story of this print has a happy ending. Except I wouldn’t call that a moral. And, as for my nights, I’ll keep you updated if they get any steamier than they are now….”

His mother shoots him a look, and the son holds his tongue.

Their rhythms have started to diverge. His mother continues talking about Hollywood stars and their comedies and musicals, about the theaters where she watched them, and about what happened that afternoon at the Coliseum. Ah, the old story of when they projected The Love Parade in English, one of the first talkies, says the son at the same time as the mother, who isn’t fazed by his parody. When the stars started speaking that incomprehensible language, the audience got up in arms, of course; the theater owner stopped the projection, of course, amid shouts from adults and crying kids; the ruckus ended with the police’s arrival, of course, and the schedule continued the following weeks with a new print, but with the English dialogue muted and the only sound the songs by Maurice Chevalier! What a fabulous film, and what songs. Wasn’t it a marvelous story?

“What year was it released?”

She shifts her childlike expression.

“No, you won’t get me to fall for that trick. Getting older is the only way to rejuvenate oneself; it’s very interesting.”

Then the mother says that the son already knows what she’ll say.

“I can’t remember—I have other things to think about,” but she can’t help wondering why he asked the question. “Ah, I get it. Yes, sir. You aren’t thinking about Chevalier’s songs, but about Colbert’s half pajama! Well, yes, of course, you guessed it, although just by chance: the movie is dated the same year as your smutty drawing.”

She finishes the sentence with a short, mocking laugh; she snuffs out her half-smoked cigarette in the ashtray and hungrily attacks the second course.

The reasons why a son explains some things to his mother are as obscure, if not more so, than the reasons why he hides other things. At first glance, in this case, the filial confidences about an erotic drawing are motivated by two ancient affinities: hunger and violence. The son is always hungry, a trait his mother applauds, and he always eats violently, voraciously, a trait he shares with his mother. The meticulousness of the desire with which the son now, over dessert, sketches with words the Picassian scene he will soon possess is also hunger and violence. A man with a small body and a prominent head looks from a corner, his eyes two black holes, the expansive forms of a female mass that advances, the body of a woman with bold rhythm, a carnal force springing forth from her skeleton.

The mother listens attentively, captivated by the vigorous and nevertheless fearful lines her son’s words trace. He evokes a treasure that will soon be his and, at the same time, depicts a sexual fantasy. From the past or perhaps the future. The mother doesn’t quite understand his obsession with precisely that drawing; it’s more of a punch to the genitals than an enduring scene. The son orders another dessert, a nostalgic concoction of flan with tinned fruit, ice cream, and whipped cream that’s called a pajama, asking his mother if she’ll eat half. “Of course, after what I told you about Claudette Colbert,” she laughs, and when they bring it to the table, the son barely has a few bites, because his mother eats almost all of it while he talks.

Now he explains the story of the engraving: when exactly Picasso made it; who the model was; in what precise state of sexual activity the painter had deemed it finished; who it was he gave it to, to take from his studio on Grands-Augustins; how many refugees from the Spanish war benefited directly or indirectly from its sale. He lingered on details about the Catalan writers who, forced to leave the Roissy-en-Brie castle when the new war caught up with them, divided up the money from the sale of the engraving—some embarking to the Americas, while others established themselves in Paris, from where they would soon end up fleeing, sadly, when the Nazis entered the city—while yet others would survive in Occupied France. The engraving spins around and around in the mother’s imagination, now sexual fetish, now document of exile. She orders a Calvados when she sees that her son still has more to explain. The current owner is pathetic, she hears him say.

“He doesn’t know anything about the history of the print or how it ended up in his father’s hands…. We still have to hash out the price, but today’s the day. Then maybe I’ll explain to him how Picasso signed it.”

That’s the part of the drawing’s past that most interests him, but he’ll relate a different version to his mother and the owner. The real reason, discovered after years of research, is very clever and, for the moment, he wants to keep it to himself. He is dying to talk about how Picasso, who never signed a work until he sold it, signed the engraving, but he doesn’t want to tell everything. The secret could lose the importance it’ll have in the future, an added value that will end up being larger and larger because only he knows it. There is only one copy.

During his investigations, he roused the curiosity of museums, collectors, experts, curators, banks, catalogue writers. He didn’t know that there were so many people hovering around a picture. No, the aura hasn’t disappeared, not in the slightest, an expert with mysterious manners confided to him, as if saying an unnameable truth that, surely, he didn’t comprehend. He was aware he was on the trail of a good piece. Maybe even a legendary one. It was unknown, had never been seen. And it had everything necessary, he realized. To triumph in the current market, the expert had added, the artwork must have an impeccable résumé: a biography, a past, a memory, an archeology, a narrative. Everything. One has to be able to present it as a testimony not only of the artist’s work but, above all, of the people around it. Layers and resonance. All sorts of echoes. If it has only been seen by the artist and some nobodies, it has no merit greater than the many other works that fill museum basements and bank vaults. Perhaps it’s true that artworks no longer have the aura they did in the nineteenth century, concluded the expert, but they have to be famous. Fame is the primordial sign of artistic worth. Legends, fame, success. The other correlatively decisive element is a good tragic biography. If a piece can offer both private tragedies and international fame, success is guaranteed.

If he keeps quiet now, he’ll come out on top, even if he never sells the engraving. If he keeps quiet now, he can leave an inheritance of indisputable value, a secret. If he keeps quiet now, he can choose his accomplices when the time is right.

Now the reasons why a son hides things from his mother enter this scene. They have to do, in this case, with two old disaffections: legacy and fear. The son is afraid of his mother’s endurance, of her indeterminate age, remaining exactly the same for the last ten years while his appearance changes, fear of the forceful skeleton and carnal bond of a woman who needs physical contact, to touch, to touch him. His mother has taken him by one hand, and with the other she brings the last spoonful of dessert to his mouth.

About his legacy, the son can’t say much, even if his subconscious could speak of it without him catching on—like right now he doesn’t catch that, in the gesture of opening his mouth and accepting the spoonful his mother offers him, there is the anxiety of that legacy, of the inheritance he wants but doesn’t know how to grab while she’s watching, which is why he hasn’t touched the pajama until she spoon-feeds it to him. Right now, if the son were to say anything about his legacy, it would be that he refuses to see his buying an engraving as some kind of substitute for the children he doesn’t want to have, that that’s his mother’s point of view but not his.

He relates the version he’s prepared for when he is the owner of the engraving.

“A young illustrator from Barcelona, who had decided not to leave Paris no matter what happened with the new war, took charge of selling the Picasso. The Picassos, actually. The engraving was then part of a series of twelve that Picasso gave in its entirety to the colony of exiles in Roissy. They were all intellectuals, writers and artists, in two groups: the Spanish and the Catalans. From what I understand, this erotic series caused a huge scandal among the exiles. They didn’t take it out of the box until almost a year later, when the French told them they had to evacuate the castle because it was needed for the French troops, that the Nazis could arrive any minute. Then they divided up the series. This drawing and three others went to the Catalans. The exiles had been arguing about the sale for days. They didn’t all agree about the matter, like so many other matters that had come up during their stay at that castle. But the drawings weren’t signed. Picasso had said that he’d sign them when they found a buyer; he wanted to know who was keeping them. The illustrator went to Picasso’s studio, still on Grands-Augustins, and asked him for guidance on the best possible way to sell the drawings. But Picasso was displeased to see the series had been split up. Agitated, he asked for details as to why, information the young man couldn’t give him, because he hadn’t taken part in the decision. What he had observed, and he’d been the first in the group to see it, was that, of the four engravings he was carrying, one of them was very different from the others. They shouldn’t have been separated, said the painter. Series have to remain complete. But then, he continued, staring straight at the young man, really, is there anything now that’s remained whole?

“Picasso,” continues the son, after a pause for a sip of wine—a very deliberate sip, thinks his mother—“accepted not knowing more details about the division of the series and didn’t want to talk about who could represent the drawings in that frantic art market, shook up from tip to tail by the imminent war in France and by the appearance of major works from the collections of Spanish museums, and Czech and Belgian ones that were also now in exile. It had been almost six years since he’d made that series. We can suppose that his mind was far away from, and at the same time close to, the emotions that had inspired the work. He picked up the four drawings that the young man had brought to him. He stared at the print that I will buy today. And he signed it.”

He doesn’t give her all the details, and some of the ones he keeps quiet are significant, relevant signs of the making of the drawing, which came into being surrounded by witnesses who do not appear in the version he’s just explained. He doesn’t give the names of the exiles who argued at the castle, or tell how the young illustrator managed to be the one chosen to find Picasso. There is still Calvados in his mother’s glass. She’d been listening with waxing interest when he spoke of Roissy and with waning interest when the story returned to the series of engravings. She perks up again when she hears what year the print was made. The same year as the Claudette Colbert film. She smiles.

She remembers Clark Gable’s bare chest.

“What was he thinking, giving erotic drawings to a bunch of exiles, sanctimonious exiles, from what you say. More than erotic, I’d call them pornographic,” she says emphatically.

“Yeah, they were pretty sanctimonious,” he confirms, pleased to see that aspect—the character of the exiles and their infighting—offered a good dose of added interest.

“How did the story end?”

“Picasso asked the young man to leave the drawings with him and come back the next day. The next afternoon he told him that, after much thought, he’d realized he couldn’t bear the idea of the series being broken up. Had he seen the complete set? No, the young illustrator hadn’t seen them all together. Maybe then you would understand, Picasso told him before asking, begging him to try to reunite the prints, to talk to the other exiles, to make the series whole again. He would buy it himself. And so the young man left. When a committee of the exiles brought the complete series back to Picasso, he signed it in front of them. Some other day, I’ll tell you how the print left Picasso’s studio again and began to have other owners.”

“And what about the young illustrator?”

“He never got to see the series reunited. The leaders of the exile groups took care of reuniting the prints and getting them to Picasso, who paid them, apparently quite handsomely.”

The mother looks at the market through the windows. The Boqueria on a Sunday, seen from the restaurant, is so vacant it’s enervating, evoking what lies beyond the shuttered food stalls, empty bars, and aisles where the light draws sinister shapes. When that place of hard work and provisioning halts, it’s as if the world has stopped spinning. She prefers to come to the restaurant during the week, when hunger feeds on the violence of seeing hung-and-quartered animals on the other side of the glass. The beasts sacrificed to the needs and pleasures of other animals transmit an order based in fear. She doesn’t say it; she doesn’t think it; she feels it at a point in her skeleton that sends orders to her eyes. But her eyes immediately banish the memory of the images of death and slaughtered meat. She wasn’t part of the exile, not among those who left nor among those who remained in a state of inner exile. She had only been out of the country once, in the fifties, to France. She maintained the happy, frivolous, innocent mien she’d had during the long postwar period. She was willing to pay any price, with a willingness that bordered on ferocity, to keep her youth from being snatched away from her. She likes Claudette Colbert because she was the first actress who seemed modern, she wasn’t a traditional woman or a femme fatale, she dared to do as she pleased in every way, and, besides, she was often a millionaire’s daughter. She laughs. Claudette never crossed the line, but she knew how to make sure others toed it. Always game, never pompous or disavowing her childish innocence. Frightened if need be, ridiculous without a second thought, always proud. A comedienne from head to toe, especially in that movie with Gable. Her son thinks it’s just a popcorn movie, and while it really is entertaining, if he watched some of the scenes closely he would find a meaning that transcends the passage of time. Like all the scenes on the bus, especially the one where they’re waiting, when the vehicle stops to get gas and neither Colbert nor Gable moves from the sidewalk. They both desire each other, but they don’t know how to make contact. In one corner of the screen, she, her eyes two black holes, frightened, sees him, compelled by an impulse far from innocent, determined, an expansive male form that advances toward her, enraged, with boundless carnal force.

The movie watcher knows that Gable is looking past Colbert, that he’s just seen a thief steal the girl’s suitcase, but the shot of her eyes, wide at his aggressiveness, says something else.

The mother has her own secrets. But the son has no interest in them. Violence and hunger, legacy and fear bind them. There are things she knows about him, and he knows about her, with no need for explicitness. But the story of the erotic drawing—It’s a print, Mama—has stirred up waters cemented behind memory’s niches. The son hasn’t paid any attention to her evocations of an old film he doesn’t remember at all and has no interest in. He turns his eyes, piqued, toward his mother when he hears her say that perhaps she knows how the drawing made its way out of Picasso’s studio again.

“He was already living in southern France by then, in a chateau near Aix-en-Provence, an imposing fortress.”

The son would ask himself, if he realized, why a mother hides things from or explains things to her son. He doesn’t realize. He is too focused on her words. It is not the version he tells everyone.

“It was one of those short trips your father made in his taxi, that time he had some business over the border and told me to come with him. That was the only time he brought me along. I had never traveled that far before. We went through La Jonquera at night. When the civil guards asked for our papers, your father hugged and tickled me… I turned red with laughter, I couldn’t stop laughing. The officer was not amused, you can imagine. He took his time reviewing our documents, asking us all sorts of things about where we lived in Barcelona, and your father said that, after years, we finally had two days off and we could go on a honeymoon. It was completely dark, and I was holding in my laughter as best I could. It was an adventure. Finally your father and I were returning to our youthful adventures. We’d had so many laughs…. The officer opened up the hood and trunk, he checked the underside of the car, and he admonished us that this was no time to be heading out on a honeymoon, even if it was long overdue. You set out on your honeymoon in the morning, not at night, he muttered. After nearly an hour, he let us through. The curves on the way into France made me nauseous, and we had to stop so I could vomit. We slept in a village near Perpignan. The next day everything was lovely. We headed to Aix, where your father had to meet up with some people. He left me alone on the grand boulevard. I still can recall the enormous, tall trees, a dome of leaves over the avenue. Your father came back three hours later, and we went to Vauvenargues.”

She drinks a little more of her Calvados and continues.

“We went into one of the bars, he greeted someone who seemed like the owner, and they both went into the back room. I waited at one of the tables. There were no other customers in there, just a girl, about twelve years old, who was doing homework at a table in the back. Every once in a while, she stole a glance at me, bashfully. I left the bar and crossed the street. At a small scenic overlook on the river, I saw the fortress. That’s Picasso’s castle, your father told me when he came out of the bar. It was the first time I’d heard that name. I didn’t know who he was. I was even surprised to hear your father talking about him as if he were someone I should’ve known. He’s a famous painter—that’s all you need to know, he said. I have to bring something of his to Barcelona, he added when we were walking back to the taxi. Is it dangerous? I asked, keyed up by the adventure, rekindled that night after so many dark, dirty years, black like cassocks, years we’d had to live as if we were happy, and occasionally we were. It could be, said your father. It could be dangerous, but it won’t be.”

His mother speaks quickly. She looks her son in the face. It had been a long time since they’d last spoken about his father. She sees something shifting inside her son, something between spite and annoyance, between knowing more and being the center of attention again, between hunger and fear, violence and legacy. His mother waits for a sign. His desire to know more wins out, but the annoyance and spite still make their presence known. He gestures with one hand for her to continue, as he blinks in quick succession.

“We spent the other night in the same village near Perpignan. Your father was more nervous than usual, and that worried me. I thought we’d have problems at the border, of course. He denied it, but we lay in bed like two strangers. Something wasn’t right. I turned on the light, and I decided to ask him what he was doing at the bar in Vauvenargues. It’s better if you don’t ask, he answered. It was hot. Your father was only wearing pajama pants; I always liked seeing his chest…. I want to know, I insisted. Otherwise why did you bring me there? I don’t get involved in your business, you know that, but this time you got me involved. You’re right, he said, and besides, I’ll have to ask you to carry something on you; the guard won’t look at you so closely. But didn’t you say it wasn’t dangerous? It won’t be. It won’t be, if we don’t get nervous. He got out of bed, and from the lining of the shoulder of his coat, he pulled out a very thin package wrapped in newspaper. He unwrapped it and showed it to me. It was your drawing.”

The son doesn’t say anything.

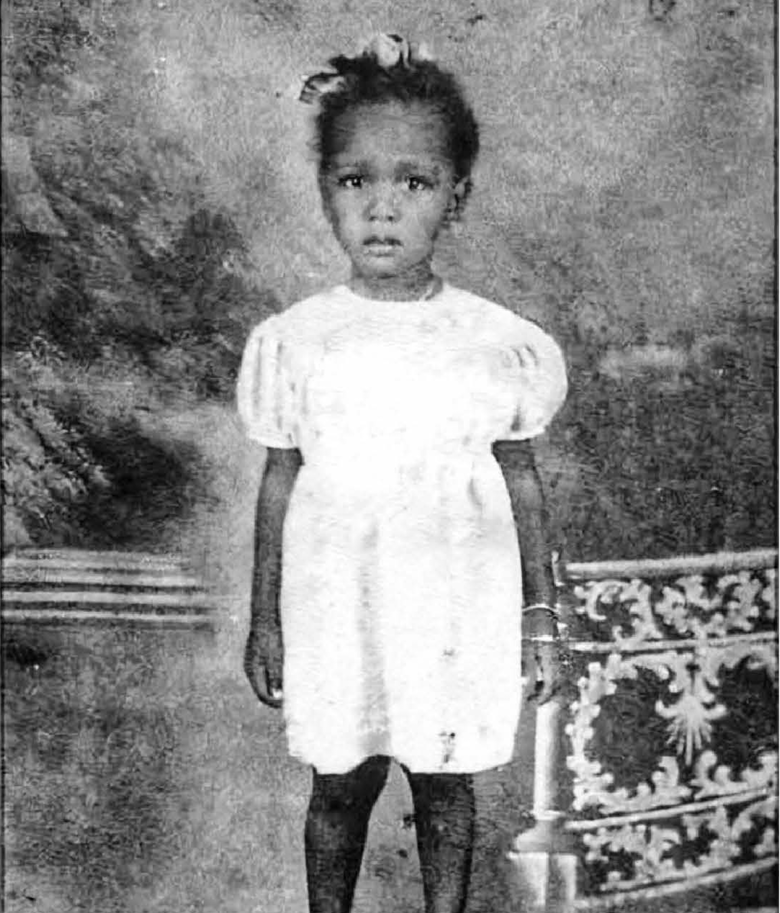

“I opened my eyes wider and wider until my lids hurt and I shut them, suddenly. I also shut off the light. I still remember the pitch-black eyes of the little man, who I now know is Picasso himself—his fear of the woman he sees there, the woman hurtling toward him, like a very strong wind that will carry him off, the little man’s you-know-whats all frightened, withered, as if someone wants to do them harm. I don’t know if you can call it an erotic drawing… although, well, maybe, your father thought so, that night… very much so.”

The woman orders another Calvados. The young waiter looks at them as he pours her drink.

“The next day we crossed the border again, with a similar delay as the first time. It was still a total, unanticipated adventure, of the kind I’d enjoyed so much in movies. We didn’t talk any more about the drawing. Until one day he said that maybe we could make more from that sort of mission than from smuggling oil and provisions from farmers in the Prat….”

His mother isn’t telling the whole truth either. She leaves out relevant details, indications, and fragments of a story that she doesn’t want to part with, episodes she doesn’t want to admit to. Her body revealed that night, gestures she would later repeat in other rooms, with the drawing in view—a drawing that, for a few weeks, was theirs. The violence of the scene depicted opened her lips and the hunger of her erotic companion, fear added its stinking and powerful song, and the lovers transmitted it to each other.

Her son looks at the bill the waiter has just brought over and pays with a credit card. For years he’s suspected (or was it a dream?) that his father had had dealings with the Picasso drawing, a suspicion (or was it a nightmare?) that, until now, he’d had no proof of and that was the personal reason—confidential, he calls it, and I’m confident no one else cares, he would add—for his dedication to reconstructing the history behind the erotic scene and, in the end, all his efforts to gather up the money and finally buy it that afternoon. Up until now, he had only found vague indications. None of his informants had been able to tell him who the taxi driver was, the one who had kidnapped the drawing for three months and feverishly kept it for himself. Wild with jealousy, said some; in dirty dealings with the drawing, according to others.

None of the exiles from Roissy whom he’d manage to speak to had known anything about it; that was a story of the postwar period. The son wasn’t expecting information but just some clue, whether they’d heard tell of it when they’d returned from exile. He’d gone to see some writers in Terrassa and, in Romanyà de la Selva, another writer who’d become famous. All three of them clearly remembered the drawing being at the castle in Roissy-en-Brie and the arguments it had provoked, but none of them wanted to go into detail. The ones in Terrassa had only mentioned that for them, as a couple, Picasso’s series had been of the utmost importance. The wild nights at Roissy, the forest…, said the writer Murià while her husband, the poet Bartra, smiled. The other writer, the one in Romanyà, a small town hidden atop a mountain range covered with dolmens and other prehistoric remains, didn’t want to open the door. She finally did after he insisted, when, through the intercom, she’d heard him say that he only wanted to talk about an engraving by Picasso. She allowed him in but, for a good long while, didn’t say a word; she just listened while he talked and talked. The name Roissy didn’t seem to evoke anything for her, and she only reluctantly admitted that she vaguely remembered the matter of the erotic series. But, when she walked him to the door, she suggested he go find the greatest expert on Picasso, who lived right there in Barcelona, the poet Palau. He was surprised to hear himself say to that older woman he’d never met before, with her impenetrable yet ardent beauty, that the reasons behind his investigation were intimate ones. The writer Rodoreda told him to make no mistake, that the poet Palau was not any old expert, and that he knew everything about Picasso’s erotic drawings, and even more about intimacy.

What stirs his insides—as his mother tries to decipher what is going on in his mind, unnerved by his silence—is what he cannot explain. The poet Palau had been very graphic. The scene:

A nearby brothel, on Carrer de la Boqueria, right in front of the market, by night. A couple acts out the erotic scenes of Picasso they have smuggled in, trafficking sanctioned by dignitaries in the city and the diocese. No, the poet Palau didn’t know their names. He didn’t want to, either. Poetry springs forth from the wells of the unsaid, he declared in parting. And the unsaid was probably, he warned, the best way to find the engraving, which might be at an address in the Sants district that he jotted down on a piece of paper. And, indeed, that was where it was.

He looks out from the restaurant. Before him, a shaft of light traverses the market and heads straight out onto the Rambla. It seems to him that the shaft comes from the most exhausted nerve in his brain.

He can’t speak about it anymore. Silence. The poet is right.

He turns toward his mother, who is motionless in her chair, sitting up straight at the table. From her tense, fixed gaze, he understands that she sees the scene. She is watching it inside herself, and now also inside him. Like an image that returns in leaps and bounds from a distance and is capable of slicing the innards of any living animal that tries to stop it, big or small. The woman covers her face with her hands.

“It’ll all be over today, Mother. There’s no need to lay it on so thick.”

“Let me explain it to you, son. Those years…”

“It’s okay—we’ll put an end to it today. This story is ours alone, no one else’s. It was yours and, now, it will be mine.”

Mercè Ibarz is a writer, essayist, cultural researcher, and journalist. Her work includes novels, short stories, and biographies. She is currently a professor of visual arts at the Pompeu Fabra University and a columnist for El País and VilaWeb. Her work has appeared in Best European Fiction 2011 and New Catalan Fiction.

Mara Faye Lethem is a writer, researcher, and literary translator. Winner of the inaugural Spain-USA Foundation Translation Award for Max Besora’s The Adventures and Misadventures of Extraordinary and Admirable Joan Orpí, Conquistador and Founder of New Catalonia, she was also recently awarded the Joan Baptiste Cendrós International Prize for her contributions to Catalan literature.