By RUONAN ZHENG

This piece is part of a special portfolio featuring new and queer voices from China. Read more from the portfolio here.

1. May 2021

At an assignment in Xinjiang, I am covering a rising female photographer, club-hopping with her and her boyfriend. Amidst glittering disco balls, fast drum beats, and fake US dollars tossed around by a random rapper, I am introduced to a guy who used to work for Vice China, making short documentaries. His exact greeting was: “Send my best regards to the bosses; I too graduated from there.” We exchanged our WeChats, and he pulled off some crazy dance moves on the floor afterward. I didn’t hear from him again but have enjoyed the hikes and mountain scenery posted on his WeChat Moments ever since.

“Graduated” is a word many ex-employees of Vice China use to describe their experience after leaving the company. Our time there felt as if we were a bunch of undergrads taking wacky tequila shots in the office, then still coming in hungover the next morning because there was nowhere better to go. Near the end of Vice China’s existence, Simon, one of the OGs who had worked for them since the beginning, reminisced about an end-of-the-year company cruise party, recalling those times as a dream. Back then, he did a little bit of everything—editorial, commercial, social media. There was always stuff to do, partnerships to form, and, of course, money from advertisers to spend. All the alcohol we ingested and the battles we fought with clients were preparing us for life after, in the cruel outside world.

The allure of working at Vice was very real for a twenty-something, especially for a Chinese kid. The Western influence took root and prospered at Vice China, which opposed everything a normal job in China entailed. To be recruited meant becoming part of a cool-kid club, access to a social currency, a guaranteed adventurous time.

2. September 2009

I leave Beijing for high school in the States after the Olympics, 2009, just as the city is becoming livelier than ever. Missing that became one of my biggest regrets. In SF and NYC, I dream about the raw cultural scene in Beijing. I watch and rewatch the Vice China skater documentary series, obsessing over the sleek sound of skateboard wheels hitting the concrete as they dodged Chengguan Daye (Mandarin slang for the security guards). The dark hutong nights folded into so many cheap beers and 5 a.m.’s.

Looking back, these short documentaries were fresh and achingly embarrassing at times, like coming-of-age films. The growing pains flowed out of the screen, with fast-paced frames cutting in like riding a rollercoaster without safety measures. You never knew which second you were going to be thrown off of the normal track of life by the weight of gravity.

3. June 2016

When I first applied for a position at Vice China, it was my first year in New York. I was fresh out of college, jobless, living in a windowless apartment in Bushwick after some dangerous couch surfing. I had one year on my student visa to figure out what to do. Like all hipster-wannabes in a typical New Yorker-wannabe manner, I set up a website, GoDaddy’ed the domain for half a year and wrote about the characters I met in the Big Apple, in Mandarin, mimicking the Vice style. I talked to an Israeli painter in her 40s; we bonded over the book How To Be a Bitch: How Women Who Have It All Actually Have It All. I had a totally bizarre brunch meeting discussing fashion in China, starring Yuesai, a century-year-old skincare mogul and NYC socialite. I didn’t have many ambitious intentions for my little blog. It was more of a “Hey, I am here!”—leaving some sort of trace in a cutthroat competitive landscape for creatives.

My personal blog documenting characters I met in NYC, which has long since vanished from the web. Only screenshots survive.

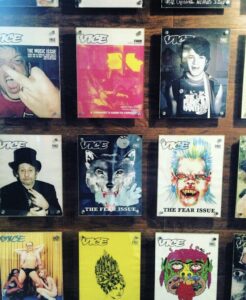

Home in Beijing for the summer, I have an interview with a girl working at Vice China. I reached out to her saying I wanted to do an interview with her for my blog. I remembering walking up a flight of steps to the office, one wall entirely filled with Vice magazine covers, which had pictures of a huge red tongue or girls in piercings, screaming loudly. It was a failed interview, awkward to say the least. I just remembered staring at the cup of kombucha she had and blanking out on words. My mouth was so dry, and I wanted to get a sip of it so badly. Back in New York, I got a job doing business reporting and kept browsing the Vice China website, vowing to try again.

The wall with legendary Vice magazine front covers.

4. December 2015

The Edison Chen documentary brings Vice China into popularity. Chen, dubbed ‘The Godfather” of streetwear in China, initially rose to fame as a successful actor and singer, only to have his career derailed by a sex scandal in 2008. Ten years later, he embarked on rebuilding his image by launching his streetwear brand, which quickly soared to a valuation in the millions. Vice’s documentary chronicles Chen’s comeback story, encapsulating the emerging spirit of Chinese hip-hop: the narrative of an underdog overcoming obstacles to achieve success. The documentary brings up Chen’s brand and contributes to the growing popularity of sneakers in China; and after the documentary’s release, Vice China is now synonymous with Edison Chen, earning a reputation as a media label associated with everything rebellious, akin to a punk kids club.

5. August 2020

Four years after my first time in the Vice China office, I return to China and interview for a full-time job at BIEDE. BIEDE is Vice China’s new name—a rebrand. Over the past few years, much has changed; many OG staff left, and female content was on the rise. BIEDE Girls, the feminist wing that used to be Vice’s “Broadly” column, dominated.

The job I applied for was to amplify the voice of BIEDE, a content marketing role. To demonstrate I could be a fun employee, I submitted a video of me doing a stand up talking about vibrator for two minutes straight, which my co-worker said was a catch. I was desperate.

On the day of the face-to-face interview, I put on my good luck silver hoops, borrowed my mom’s white suit jacket, and headed to the subway. The office had moved from the hutong to a low-rise building; the glass door featured a big pink eye poster, precisely the Vice-cult style I had anticipated. Inside, there were half-filled office desks, and it was dead quiet. Visually, it appeared busy, with a bass in the corner, various cartoonish things, posters scattered around, and a few 18+ manga books. The interview wasn’t long, and the conversation deadened when I couldn’t elaborate on the latest Hong Sang-soo movie, who had been my ex’s favorite director.

When I met the boss of the company, Meng, who had been a band manager before coming to Vice, he asked me about my favorite project of theirs. I mentioned the Edison Chen documentary, which played a role in rebranding the actor who once orchestrated the leak of actresses’ nude photos, giving him a new foothold in streetwear fashion. Meng let go of a bitter smile and offered a full speech about the new direction BIE was undertaking. The interview was shorter than I had expected, and I left somewhat confused. There was an odd aura surrounding the space; it was the opposite of what I had imagined. Instead of loud music and cracking jokes, it had an easy environment—more precisely, it felt dead, weak, like a dimmed light. A week later, I get the news that I’m hired.

6. July 2018

The leader of the editorial team, my boss, was Alex. She was known as the host of the podcast BIEGirls and was dubbed the young Li Yinhe (after a famous sexologist in China). She had a Ph.D. in sex studies, so she was really good at dissecting gender topics. With thousands of followers sharing their stories and riding the #MeToo wave, she garnered a decent following on social media. If she was angry, you could hear it from the speed at which she typed.

My first assignment was writing reviews about a vibrator, something I had in my joke application. I wrote about my interaction with my parents when they saw it and how the battery broke before I could use it.

At BIE, the girls in the editorial room barely spoke with the boys from other departments. One time, during a company outing dinner, I had a few too many baijiu drinks and started to talk to those boys, making quite a scene. We shared a common admiration towards hip hop culture, and I commented on how they are being themselves unapologetically.

I thought, it’s not that they don’t respect women, they just couldn’t catch up with the changes regarding gender dynamics, and weren’t aware of where the new boundaries lay. They tried to censor their vulgar comments towards women or add disclaimers. But the female staff was still taken aback.

7. August 2020

The writers at Vice China, now BIEDE, use so few words and almost take pride in identifying themselves as socially phobic. They converse with each other via WeChat while sitting just across from each other. It makes sense why the office is so quiet.

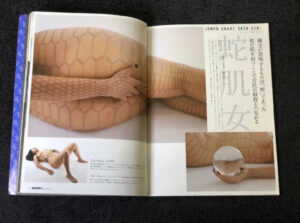

The other new editor, Rice, is markedly different from me. She is immersed in underground culture and exceptional at engaging in conversations with strangers but, according to her, incapable of maintaining long-term relationships with people. One of the first stories she writes is about a “dragon girl” with ink all over her body. She specializes in a type of tattoo called “meat-curve,” which was mostly tattooed onto girls, each curve symbolizing a new life and the healing of a self-inflicted wound.

A photo of the “dragon girl,” an interview subject which our writer Rice had been following for a long time. The piece is meant to turn around the gendered stereotypes of female tattoo artists and self-harm.

Rice is fixated on S&M and rubber wear, which she uses as a portal for her curiosity about power dynamics. In one story, she interviews a man who likes cross-dressing, but focuses more on his relationship with his wife. She asks whether his wife is jealous of the husband’s cross-dressing personality.

Then there is Caicai: possibly the most gifted writer I had ever come across in Chinese reporting. She is a quintessential BIE girl—dressed in a Y2K style, with a Valley accent and an appreciation for Michel Foucault. She is also a hit machine: many of her articles surpassed the 10K page views on WeChat. Her interview style is ruthless and borderline offensive. She is remarkably observant on societal issues, venturing out to spend days on investigative reporting with Sanhe Great Gods—modern Chinese homeless—or speaking with the parents of transgender kids. In person, she is hard to get to know. She likes to bury her head behind the laptop and doesn’t engage much.

CaiCai, our best writer at the time, and the intern, both wearing a drag hairstyle and walking around the busiest shopping street in Beijing, against a Gucci sign, a testament to social class differences.

8. 2018

Hip-hop, basketball, skateboard, graffiti: the so-called “five essentials” of underground culture are now in the mainstream. The reality TV shows Dunk of China and The Rap of China, meant to hype hip-hop culture in China, gave birth of reality show influencers, hyped the cities Chengdu and Chongqing, and brought forth slang lingo like “skr skrr skrrr.” Eventually, reality show culture reached the indie rock music circle with the show The Big Band. This touched a sore spot for one of the Vice China founders, Meng, who had started his career managing those bands in the early 2000s. He yells from his desk, swinging his arms wildly: “It used to be music influencing fashion, now fashion brands dictate musicians. These people really have no culture!”

In typical BIE nature to shy away from the mainstream, our publication almost made a conscious decision to be absent from those conversations. But what was left to write about? We were only repeating the same subjects already covered years ago. What happened to the underground? Left out of the conversation, a general fatigue loomed around within the office.

9. 2021

A story about government-sponsored graffiti in Wuhan comes to light. The head of a local graffiti organization collaborated with the government to paint an entire subway track. This organization’s projects are mostly sponsored by the government. For example, they’ve painted an entire warehouse, and the government helped with logistics and even security. So at the subway track, it’s quite funny when a graffiti artist panics at the sight of the police, and the head guy comforts him and says, “They are here with us.”

At BIE, I’ve seen police knocking on the door and inviting my boss for a tea break more than once. Afterwards, we would have to take down certain articles on the website, which contained certain keywords. It was not a pleasant thing to do, but we do it to survive in the increasingly small margins of creative expression allowed. Why was Vice China not shut down over the years? I assumed that, like that graffiti organization in Wuhan, we had some kind of mutual understanding. When we publish articles on sensitive topics, we add a disclaimer at the beginning, using language like “Treasure this while you can read it (且读且 珍惜).”

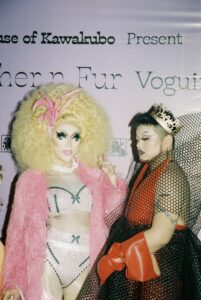

A photo of an LGBTQ+friendly voguing event in Beijing, a rare event at the time.

10. September 2021

Eventually, I’ve become tired of being part of the content machine trying to capture people’s attention. So I called it quits. We were under constant pressure to monetize every life experience to turn it into content. This deprived me of the simple pleasures of life. I didn’t blame the founders, but the fast pace of content production in China.

Online, I see a lot of critics of BIE who say the old Vice tone would never come back, neither would the edge. The office is more “baizuo” now—a term meaning “white left,” the white liberals of the West. The critics say our content is heavy on digesting certain theories and breaking them down, not so much the gonzo journalism of before. If you look at the composition of the staff, most have their graduate degrees from overseas and are predominantly far-left liberalists. I and Rice, hired at the same time, certainly fall into this category.

After I leave BIE, I interview at a major rival, NOWNESS, a media and content company which garnered favors from top advertisers like Chanel and often had photo shoots with celebrities. I read a quote from the founder who states: “It’s impossible to be real.” I feel that he’s talking about the media landscape in China and approaching reality as a subject matter.

In 2024, after freelancing for 3 years, I join a new demanding full-time job at a new company, adapting to the 996 lifestyle—working 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., 6 days a week. I guess I still have questions about the media landscape, I want to get to the bottom of it, how to create content for good without depriving me of my sense of self.

11. 2024

As I write this week, news just surfaced that the Vice website, the former headquarters, will be shut down. Friends who know people working or used to work there scrambled for tutorials on how to save their work before it vanishes.

A week before I left BIE, I did the same, downloading articles and organizing them into separate folders on my laptop, as if preserving a national treasure. I can still feel the feeling of burnout, and nightmares about being chased by deadlines. It’s hard to imagine how the founders of BIE, Madi and Meng, stood for so long. I remember Meng, saying that the longest-running employee was actually the cleaning ayi; she has been there since the beginning.

12.

In the end, who were the VICE kids? We shared our favorite Hunan dishes for takeout, we had our insecurities about money and whether we were sociable enough. None of us wanted to have kids and generally, we concurred that this world is messed up. The oldest among us were in their mid-forties, but the atmosphere always remained adolescent. The “me vs them” mentality remained strong throughout. There was always an enemy, whether it was a coworker complaining about our boss because of the low pay, or the enemy of censorship, or the enemy of capitalism…last time when I checked in with one of the founders, Madi, we both said we thought our common enemy was big data and the Internet. But I keep thinking: who exactly is the enemy here? Does an underground media company always need an enemy to stay alive?

After I left, a few friends asked me, “What exactly was Vice? How do you define the people at Vice?” On the surface, it wasn’t just about what was weird or “vices” in life counting as experience. The Vice reporters I met tended to have a strong backbone and humor—which are qualities I see now in my friends, my uncle, and even monks I have encountered on temple retreats. Though Vice China has died, its existence opened up a whole alternative realm for me, revealing the types of cultural institutions that exist, the weird characters who are still in the underground in Beijing, and the desire to be in the places where things are likely to happen. All hail Vice, and hail to those people who possess that kind of spirit. May it never die.

Ruonan (Rachel) Zheng is a writer and documentary filmmaker based in Beijing. Her work is in VICE, BIE别的, Jing Daily, Quartz, SCMP, and more. Follow her on Substack, 3rd Culture Kids, a space to explore the intimate intersections between art and culture in China.