Jonathon Keats has been described by The New Yorker as a “poet of ideas.” Keats’s latest project is the Millennium Camera, a custom-built pinhole camera with a one-thousand-year exposure time that will remain inside Amherst College’s Stearns Steeple until 3015. In May 2015, the college’s Mead Art Museum documented the intellectual and material creation of Keats’s camera, displaying its blueprints and predecessors alongside the camera itself in an exhibition titled Jonathon Keats: Photographing Deep Time. To commemorate the opening of the exhibition, Keats spoke with Vanja Malloy, the Mead’s curator of American art, about deep-time photography and about the rapidly changing nature of humanity’s relationships with its environment and its descendants. This essay has been adapted from that conversation.

In 2010, I made a camera inside a magazine. A camera you could cut out of the issue, glue, and put out in the world, and in one hundred years, the magazine, a magazine called Good, assured me they would publish the results.

If you are making a camera that’s going to be in a magazine, a camera with a hundred-year exposure, you are not in the realm of the iPhone. You are in a realm even more primitive than film photography. In order to make an exposure one hundred years in length, I exploited what art conservationists consider the bane of their existence: the tendency of materials, pigments in particular, to be fugitive; of works on paper, even paintings, to fade over time. I realized that this fading process was a way to capture an image. If you were to put a piece of black paper inside a camera and allow the light to project onto it, you would very gradually fade the paper, selectively, creating a unique image of whatever the camera is looking out on. Using a pinhole camera, which uses just a pinhole to focus whatever is in view, you can make that exposure extraordinarily long in duration. The idea with Good was that the magazine was printed on paper. If you look at any old magazine that’s been on your coffee table too long, it’s faded. Why not take that and make a virtue of it, and use that as a photographic process: make a camera, and then allow anybody to cut it out, put it out in the world?

I initially referred to these cameras as “black boxes.” In the same way that an airplane has a black box that records all that happens while in flight, these “black boxes” would record all that happens within the world, within society over a long period of time—a period of time longer than a human lifespan. They could potentially function in the same way as a black box inside an airplane: if there is a plane crash, you can figure out what happened and improve. It’s also a check on those who are using the equipment, a way in which they are being monitored. I saw the cameras in this passive role of monitoring society, with a feedback loop taking place. Surveillance is one of the biggest issues of our time. I started to think about how these might be, in fact, surveillance cameras. But surveillance in a very strange way, where the audience was not the government but rather a generation not yet born, children who are not yet here, who are most affected by every decision that we make, yet are least powerful to have any say in the decisions that transpire, both at the level of our government and our economy, and at the level of the individual city.

This led me to Berlin, a city undergoing vast rapid development, with a long and fraught history with surveillance during the twentieth century, and also the twenty-first century, in relation to our own government. Bringing surveillance cameras to Berlin and then giving them to Berliners to put out into their city for the next generation was provocative: It made what was a relatively innocuous project in a magazine, a relatively passive project, something that was activated by the city, by the people within that city. Compared to the project with Good, there was a much more formal relationship as far as how the cameras were distributed, yet it was, at the same time, crowd-sourced in the most broad sense of the term. In collaboration with a gallery called Team Titanic, I made one hundred cameras. These were a little bit different: they were a bit more durable. Cardboard does not fare well in a rainstorm, though certainly paper can last for hundreds of years, so if you had enough paper cameras, there’s a chance some of them would survive. Making the cameras out of metal improves their chances. You have a peel-off shutter mechanism with the black paper inside, and a deposit of ten euros was handed over to the gallery from anyone who wanted to take one of these cameras and hide it anywhere they wished in Berlin—telling nobody, including me, including the gallery, where they put it. So then they took responsibility, when they turned very old, for finding a child who would be willing, as an adult in the year 2114, to go out and find the camera, retrieve it, bring it back to the gallery, get the deposit of ten euros, and then there would be an exhibition.

Only the people participating knew where the cameras were specifically. Yet I wanted everybody in this city, to the fullest extent possible, to know that the cameras were out there. That’s how a surveillance camera operates in our society, or even how a black box does. There’s a sense of being watched. And so ensued our media campaign: it was in the Berlin newspapers and picked up by Reuters and various other wire services. It induced a sort of paranoia: people felt that they were being monitored. With these century cameras, you are being watched by the next generation, those not yet born. It builds a relationship over time that might change how you decide to vote, to invest, and everything else. I have no idea what will happen, whether it will work. The cameras are now out there. The photos will most likely be overexposed or underexposed, particularly because I had no say in where people put the cameras: in a dark room, for example, or in a place with an enormous amount of sunlight. It becomes a matter of statistics. But for those alive today there is an awareness that these cameras are out there. That experience then led to the Millennium Camera project.

Vanja told me about the resistance she encountered to the idea of trying to put a camera in a steeple for a thousand years. “People will not question the fact that some of these cameras will be here in a hundred years. It’s an amount of time we can conceptualize: we can think of great-grandparents that were alive a hundred years ago,” she said. “The question arose: How do we know the steeple will be here in a thousand years? How do we know Amherst will be here in a thousand years? How do we know anything in a thousand years?” At the thousand-year level there is plenty to doubt, there is plenty to question, plenty of reasons this might not work out. This ranges from the technology itself, or lack thereof, to the institutional framework in place. At Amherst, and even in Berlin, the project is as much about us, our sociopolitical relationships in our own time, and our ability to collaborate on something that goes beyond ourselves, as it is about the images that emerge at the end.

These cameras are a very poor example of any sort of scientific experiment or of photojournalism, of documentary photography. In the case of the thousand-year camera, we know where the camera is: it’s looking out on the Holyoke Range. In the case of the hundred-year camera, while we may not know specifically where they are, we know they are out there, and that is potentially affecting us. That is really the essential part of this project: even if they don’t last, these cameras operate as a mental prosthesis for each of us individually. But if they don’t last, that becomes a social portrait of us as a society. We evolved with the hand-axe; we evolved with the ability to affect our environment very locally both in place and in time. But in the past hundred years, in the past twenty, in the past five, it’s become as if we were a geological force, only at a vastly accelerated rate. We can change the world so rapidly, with a mindset that does not in any way prepare us or allow us to think of the length of time that our decisions impact.

This camera becomes a way for us to see ourselves from the far future, to reflect on the decisions that we make, but also it becomes a way to coalesce around a project in deep time. Can we, as a society, work with and around a project like this? Can we, as a society, sustain an institution such as Amherst College? Can we sustain cultural institutions, small galleries such as Team Titanic in Berlin, for just one hundred years? Are we a society where these social contracts survive, where one generation would care enough to pass these cameras on to the next, and the next generation would care enough to retrieve them, in the case of the hundred-year project? Can those structures continue to exist in the future?

I don’t plan to be here in a thousand years, but for those of you who are, what you’ll see if all goes well is not an image of a single landscape, but rather an image of change within that landscape over that very long period of time. How is that possible? To address the question at a technical level, I built the camera based on archaeological and art-historical research. The casing of the camera is made out of copper. Archaeologists know what happens to copper: it will take on a patina, and the oxidation creates a sort of protective surface that will preserve the integrity of the camera as an object, which is intentionally very simple and very small. The pinhole can’t be allowed to oxidize at all, so that is pierced through a sheet of hardened twenty-four-carat gold, and gold will not corrode. This provides integrity over the next thousand years for the means by which the image is focused.

The image is focused onto the back of the camera, which is not paper in this case. Instead it is oil paint. The pigment that I chose is a paint called rose madder. The madder root has a red color that was very much valued in antiquity, but is the bane of any conservator today. Examples of paintings from the Renaissance show that it’s not very light-fast. It is a fugitive color. And the so-called “inherent vice” of it becomes a virtue in the case of a camera like this, because we are causing it to fade.

This instability results not in an image of a single place and time, but in an image over time. For simplicity’s sake, let’s imagine that the Holyoke Range, which currently is forested, through climate change becomes grassland. If the trees were there for two hundred years and then were gone for the remaining eight hundred, there would be the ghostly image of those trees against the bolder mountain with its grassland landscape. We’re talking about a photography of change. Think of it as a whole movie compressed into a single frame that could potentially be reconstructed in the future. You couldn’t determine the precise chronology, but in conjunction with the landscape itself, you could have a very good idea of what happened and how things changed. You could have a very good idea sociopolitically of what acted out in the world to bring about that change, especially when you move from one camera in one place to many cameras in many places around the world, as many cities, as many landscapes as possible—extending this project through the park system in the U.S., for instance, or UNESCO. To have as many perspectives as there are places and people would be truly monumental.

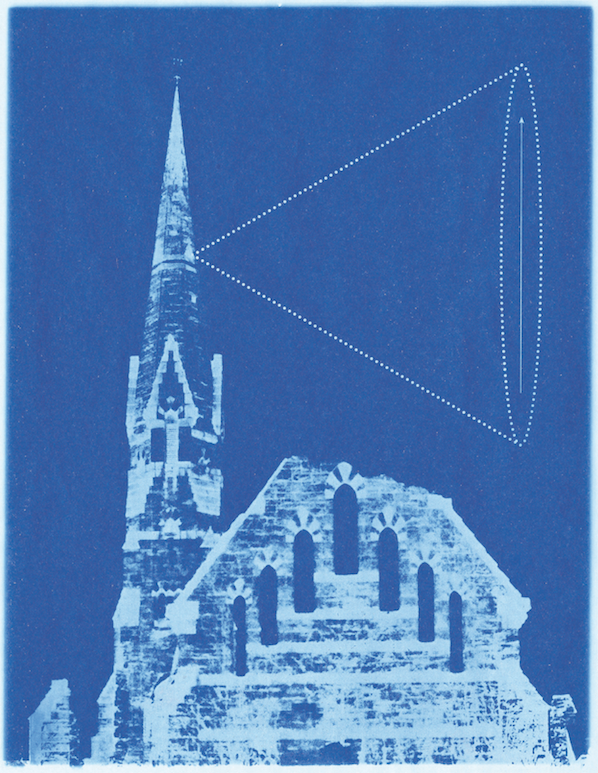

Stearns Steeple is monumental. It was one of my first points of reference here at Amherst College. I lived in Stearns Hall looking out on the steeple: that was my view for my whole freshman year. It always was this monumental presence, and it’s one of the things I identify most with Amherst College. But it is also this strange appendage of a building that is no longer here, of the church that was torn down in the 1940s. The steeple was kept for sentimental reasons, but it almost has this poignantly pointless existence at this stage, which can be activated by looking back to a time before Stearns Church, before any church, to what steeples were originally for architecturally. They were watchtowers, and, with the Millennium Camera, this becomes a watchtower with a much longer view. It becomes a new way of using a very old steeple that potentially engages and involves the community—which is what churches at some level have done historically—through this inclusive act of collectively taking in an image and sharing it, generationally, over deep time.

The camera becomes a challenge, and whether that works out or not becomes in its own right an image of the society we have and what it may become. This project is starting out here and now, but will be, I hope, in other places soon. I am now starting to talk with people who are affiliated with a tribe in New Mexico, on tribal land, to build one of these cameras into one of their dwellings. It’s a very different hierarchy in place, a very different structure, a very different way of sustaining culture through deep time. And that might well last longer than anything we come up with. Having many cameras looking out on many scenes in many places around the world, through many different structures and many systems of responsibility, becomes a way in which we can really get this global snapshot, a snapshot that snaps over the next millennium.

Make your own Century Camera out of paper! Turn to the end of the print issue, cut out your camera, and follow the simple directions. [Purchase your copy of Issue 10 here.]

Stearns Church, constructed with funds from William F. Stearns, the son of an Amherst College president, was completed in 1873. After standing for seventy-six years, the structure, excluding the steeple, was demolished in 1949, and the Mead Art Museum was built on its former site. Buildings and Grounds Collection, Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.

Stearns Steeple after the demolition of the surrounding church in 1949, shortly before the construction of the Mead. Buildings and Grounds Collection, Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.

Keats’s site plan for the Millennium Camera installation, demonstrating its position at the summit of Stearns Steeple. Courtesy of the Mead Art Museum; gift of the artist.

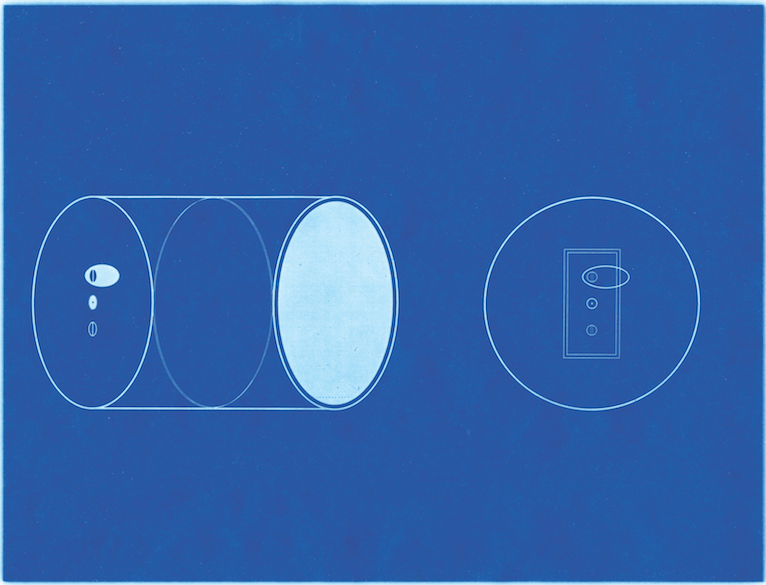

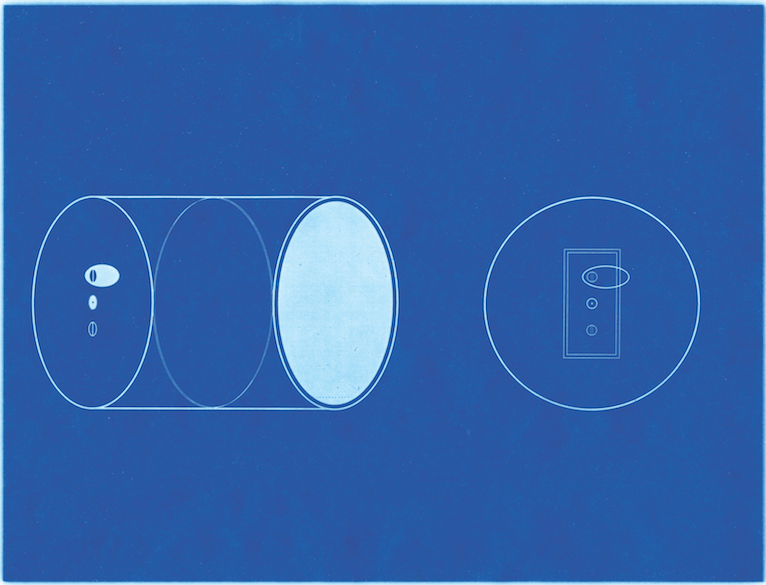

Keats’s Millennium Camera in blueprint. Courtesy of the Mead Art Museum; gift of the artist.

Keats’s Millennium Camera execution. Visible are the camera’s copper casing and 24-carat-gold aperture, as well as the rose madder pigment used for the interior of the device. Rob Mattson/Amherst College.

Prototypes of century cameras. Rob Mattson/Amherst College.

Jonathon Keats is an experimental philosopher, artist, and writer based in San Francisco. His conceptually driven interdisiplinary art projects have been exhibited at the Mead Art Museum, the Arizona State University Art Museum, and the Wellcome Collection. He is the author of six books. Oxford University Press will publish his newest book, on the legacy of Buckminster Fuller, was released in early 2016.

[Purchase your copy of Issue 10 here.]