Film by KELLY REICHARDT

Review by HANNAH GERSEN

The art critic Jerry Saltz peppers his Twitter feed with advice to artists. Recently, he wrote: “Artists: Every single second you spend on being jealous of someone else is a complete waste of life.” Reading it, I thought of Lizzy, the sculptor at the center of Kelly Reichardt’s new film. Showing Up is a dry comedy that is a love letter to anyone who finds time to make art while holding down a day job and trying not to let anxieties—which might arrive in the form of jealousy, resentment, or self-loathing—get the best of them. What makes this story unusual is that it focuses on an artist in mid-career, someone who has honed her talent and is respected by her peers, but who is not famous or conventionally successful. I can think of a lot of movies about artists at the beginning or end of their careers, charting the exciting rise or the tragic crash-and-burn, but there aren’t many filmmakers who can find the drama in the daily life of an artist diligently doing the work.

Given Reichardt’s long arc as an independent filmmaker, Showing Up feels like her most personal film, a portrait of her own disciplined pursuit of her craft. It’s also a tribute to her long collaborations with Michelle Williams, who stars as Lizzy, and with screenwriter Jonathan Raymond, who has partnered with Reichardt for six of her nine features. Raymond’s first film with Reichardt was 2006’s Old Joy, and Williams began working with her in 2008’s Wendy and Lucy. These were Reichardt’s third and fourth films, and together they seemed to crystallize her aesthetic for viewers: her slow pacing, her love of the Pacific-Northwest, her themes of friendship, community, and precarity, and, above all, her interest in telling stories about regular people surviving tough times and wrestling with uncertainty. All these elements come together in Showing Up with a light, comic touch that feels new, or was at least more buried in earlier films, where her commitment to realism sometimes bordered on dreary—and I say that as a fan. But, it’s nice to see her filming the Pacific Northwest in its sunnier season, and focusing on a character who is doing what she loves, however anxiously.

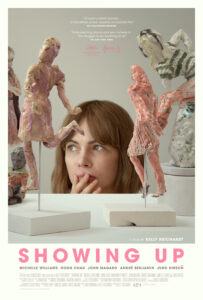

We are introduced to Lizzy through her artwork. She makes doll-like clay figures that are about two feet tall, with twirling skirts and outstretched arms. The opening credits linger on her sketches of dancing women, which she uses to develop her sculptural designs. With their joyful energy and brightly colored dresses, the sculptural women are in contrast to Lizzy herself, who rarely smiles and favors utilitarian clothing in earth tones. Williams, who has lately been portraying flamboyant, lively characters in Fosse/Verdon and The Fabelmans, tamps down her energy for Lizzy, walking with slumped shoulders and giving off a decidedly grumpy vibe. Her cat, a friendly orange tabby, is more outgoing than she is, meowing noisily for food and jumping up on the table to get attention. His purring is often the loudest sound in her basement studio, the only place where Lizzy seems to find contentment.

Although Lizzy’s life clearly revolves around her art, it’s not a reliable source of income—nor, this film gently suggests, is it for most artists, however successful they may seem to be. Lizzy supports herself by working as an administrative assistant at an art school in Portland, Oregon. Her mother is the school’s director, and through her job, Lizzy has access to a kiln, as well as a community of student artists, faculty, and visiting artists. It’s a lovely place to work, but Lizzy is tense and irritated because she’s on a deadline, trying to prepare her own work for a gallery show that will open in a week. This stressful time is made worse by the fact that she doesn’t have hot water in her apartment. Her landlord, Jo (Hong Chau), is also an artist, with two gallery shows coming up, and she tells Lizzy that she’ll fix the water heater when she’s done prepping for her shows. In the meantime, she says, Lizzy can use her apartment to shower. Lizzy is annoyed by this solution; she wants Jo to be a reliable landlord and to fix her water. Jo wants Lizzy to cut her some slack, as a friend and a fellow artist. The power dynamic between them is complicated by the fact that Jo is younger than Lizzy, and her career is on an upward trajectory. She’s also a graduate of the school where Lizzy works, and one of her upcoming shows is taking place in the school’s large, public gallery, which Lizzy helps to manage. Lizzy can’t escape Jo’s presence, which only adds to the resentment she already feels as neglected tenant.

Jo and Lizzy couldn’t be more different, temperamentally, which gives their interactions a comic flavor, rather than an antagonistic one. Jo is instinctive, joyful, self-involved, and at ease. She works in a huge industrial studio with music blaring and finds time to hang a tire swing, even with two deadlines looming. She creates large mixed-media installations that take up entire walls, using industrial materials like Styrofoam, plastic, synthetic fabrics and duct tape. She doesn’t have to fit anything into a kiln or abide by its firing schedule, nor is she beholden to a day job: her income comes from renting out her adjoining apartment and basement studio to Lizzy. The irony of the situation frustrates Lizzy to no end, but Jo doesn’t even seem to notice it. From her point of view, she’s a wonderful landlord because her rents are below market. She’s also genuinely supportive of Lizzy’s artwork, attending her shows and talking her up to other artists.

Lizzy’s work for her mother also engenders complicated power dynamics. When she asks for time off to get ready for her show, her mother grants it, but in a passive-aggressive manner that seems reserved for her daughter. Lizzy’s parents are divorced, but her father and brother live nearby, and Lizzy is the one who keeps everyone in communication with each other. Both Lizzy’s father and brother are artists, but neither is currently making art. Or rather, her brother, Sean (John Magaro), seems to be in the grip of untreated mental illness as he pursues wild conspiracy theories and digs a large hole in his backyard under the guise of art, while father (Judd Hirsch) has become bitter and complacent in old age. Magaro, who was so gentle and emotionally transparent in Reichardt’s last movie, First Cow, is almost unrecognizable as Sean, a person who radiates fury and can barely look anyone in the eyes. Lizzy’s parents are in denial about the severity of Sean’s mental breakdown, and as the film comes to its climax, we see that Lizzy is the only one in the family who is emotionally stable, and that her artistic practice seems to be connected to that inner clarity.

This isn’t really a movie that can be spoiled, and yet I don’t want to reveal too much about the delicate plot, which involves Lizzy’s cat and an injured pigeon that Jo and Lizzy care for, heightening the tension between them. (Like the orange tabby in Inside Llewyn Davis, Lizzy’s cat is a mischievous presence throughout the film.) Reichardt has long been interested in the relationships that humans form with animals, and takes them more seriously than most directors, observing how they interact in domestic spaces and affect each other’s circumstances. This is probably most evident in a film like First Cow, whose plot revolves around the arrival and use of a dairy cow, but you can also see it in the horses in Certain Women and Meek’s Cutoff, and of course, in Wendy and Lucy, which revolves around a young woman’s search for her lost dog. In Showing Up, the animals have a symbolic aspect, and seem to express aspects of Lizzy’s psyche that she hides behind her gruff demeanor.

But the heart of this film is Lizzy showing up for her own artwork. We see her working in her studio late into the night, shaping wet clay with wooden tools, knives, and her bare hands, and glazing her creations in unexpected colors. We learn about the kiln schedule and watch as Lizzy places her sculptures into the oven, hoping for the best when she retrieves them, later. Except for the kiln reveals, these sequences are not especially dramatic, but they show the happiness that Lizzy finds in her work. The camera often lingers on the peaceful faces of the sculptures that Lizzy is working on, rather than on Lizzy’s face, a choice that seems to regard the dancing women as more revealing of Lizzy’s emotional state than Lizzy herself. I’m not sure if Reichardt intended such a psychological interpretation, but there is something surreal about the film’s final scenes, in which all the characters are gathered for Lizzy’s gallery opening, mingling around her sculptures and picking petty fights with each other. Lizzy in the fray, trying to manage all the disparate elements of her life, like someone stuck in an anxiety dream. In the closing shot, she achieves a kind of freedom and peace that has eluded her. Knowing Lizzy, it’s probably a fleeting contentment, but it feels earned just the same.

The soundtrack throughout the movie is minimal, and in the studio scenes we only hear what Lizzy hears: the loud purring of her cat, the gentle warble of pigeons outside of the basement, and the low hum of cars passing by on the street. Her studio is her place for uninterrupted flow and it’s easy to understand why she’s always trying to get back to it. So many artists (myself included) have a fantasy of working uninterrupted, for as long as we like, but Showing Up gently argues that the demands of the outer world can be embraced as part of the process of making art. To end as I began, here’s another quote from Jerry Saltz (again, taken from his Twitter feed): “One of the greatest things about being an artist is there is no in-between time. You are working all the time. The ‘in-between’ time is a furnace of ideas. It’s like there’s this locomotive always going and you’re on it. This is a life lived in art.”

Hannah Gersen is the author of Home Field. Her second novel is forthcoming from Little A in 2024. In her monthly newsletter, Thelma & Alice, she recommends movies written and directed by women: https://thelmaandalice.substack.com