Books by RENATA ADLER

Reviewed by

Renata Adler dedicated Speedboat (1976) and Pitch Dark (1981) for “A.” and “B.,” and like two LP sides, the novels, newly reissued by New York Review Books, are variations in a radical approach to fiction. They diametrically oppose E.M. Forster’s formulation that narrative is causation—not “merely” A happened, then B happened, but A caused B. Adler puts A next to X, with no apparent causal connection or temporal sequence. Many characters appear only once. But episodes’ consistent sentence structure and types of characters create a coherent tone. Its effect is hypnotic.

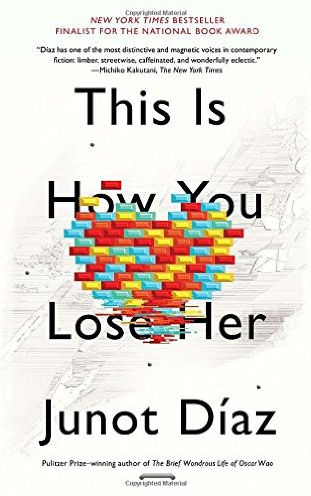

This is How You Lose Her

This is How You Lose Her