By ROB HARDY

1.

I wrote my first college paper on a new Smith Corona electric typewriter and my last on an Osborne compact word processor. I started graduate school with a turntable and ended with a compact disc player. When the boys were born, I took their pictures on film that had to be sent away to be developed. The pictures came back to fill albums and shoeboxes. When the boys graduated from high school, I uploaded the photos to my computer and posted them on Facebook.

I can recite a litany of banks and businesses that have merged and disappeared since we moved to Minnesota in 1990: we banked at Norwest Bank; our gas and electricity came from Northern States Power; we flew on Northwest Airlines; our telephone—

what was the name of our telephone company?

2.

On the island we light candles and kerosene mantle lamps bought from the Amish. We grind our coffee in a hand-cranked mill. We read old books shelved in generations of dust. Balsam poplars wander onto the field where the children played. When we can’t remember something, there’s no Google—only the one-volume encyclopedia published over sixty years ago that knows almost nothing of our lives. There’s no data coverage. Although we’re on an island in Lake Huron, our phone company thinks we’ve gone to another country.

But here we always know the direction of the wind, and with it the prospects of fair or rainy weather. We sigh at the east wind. We watch the movement of the waves. We learn the names of plants, and measure our season by their flowering. Indian paintbrush in June. Fringed gentians in August.

3.

Gram’s memory stores loops of conversation seconds long. She repeats them like the waves. She has forgotten the names of most of her friends, and has to be reminded of the names of her grandchildren. Often what remains is simply the feeling of pleasure—the feeling that there has been pleasure, that her life up to now has been good. Her smiles are found objects. Washed ashore by a wave of memory that has already receded.

But she remembers traveling to more places in her ninety-one years than she has actually travelled to. Jab a finger at a spinning globe, and she has been there. Dad and I went there. Dad and I have been to the Azores. Dad and I have been to Crete. The loop of conversation plays. Her memories—long train journeys, walks in the country, a scene on a postcard—have become portable, transferable to any place you can mention.

On the island, in our house in Minnesota, in my sister-in-law’s house in England, she smiles and says, “This is my home.” But she can’t untangle the threads of relationship that bind her to the place.

We take her out to a new restaurant and she says, “I’ve been here before.” The walk from the door to the table is temporarily misfiled as an old memory. A minute ago is already another time. Nothing is new. Everything is new.

4.

On the island there are two kinds of novels on the shelves. First, there are classic novels that provide some new insight or pleasure with each successive reading. These books have been long lived-in and loved, and each reading brings a deepening of experience. Pride and Prejudice belongs to this class of novel. Second, there are books so light that the pleasure they give, though great, is momentary, and seldom accompanied by any lasting impression. To this class of novel belongs Margery Sharp’s The Nutmeg Tree.

I think I may have read it every summer—sitting on the south porch, looking up from time to time at the cedars and the confusion of warblers I will see again back home in another month, passing through on their migration south.

5.

After dinner we found an old victrola in the boathouse. We cranked it up and listened to a 78 of “If I Only Had a Brain” from The Wizard of Oz. The tune will be in our heads for days. The sunset faded and the stars flooded into the darkness. The familiar constellations almost lost in the infinitude of stars. The white shimmer of the Milky Way and the green shimmer of the Northern Lights. Standing on the dock, I saw three shooting stars that no one else saw. But everyone else saw another shooting star I didn’t see. The beams of our flashlights caught crayfish coming out from under the dock.

In the unclocked hours of night, in the cavernous dark, it comes to me. USWest. The name of the phone company. Everyone else is sleeping.

Rob Hardy is the first Poet Laureate of Northfield, Minnesota. His essays have appeared in New England Review, Ploughshares, North Dakota Quarterly, New Letters, and elsewhere. He’s the author of Domestication: Collected Poems 1996-2016 (Up On Big Rock Poetry Series 2017) and Aeschylus, The Oresteia: An Adaptation (Hero Now Theatre 2017).

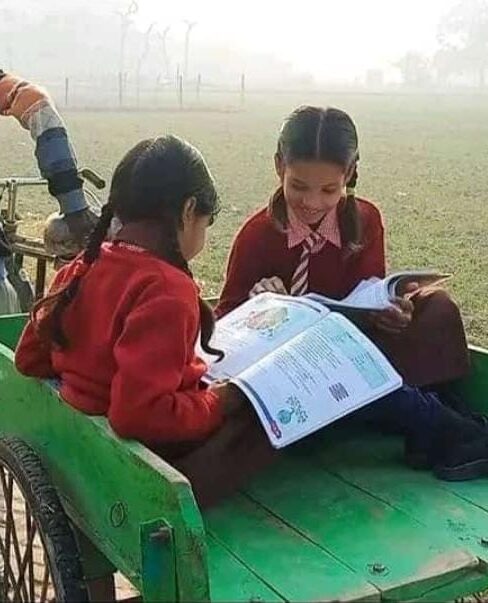

Photo by author.