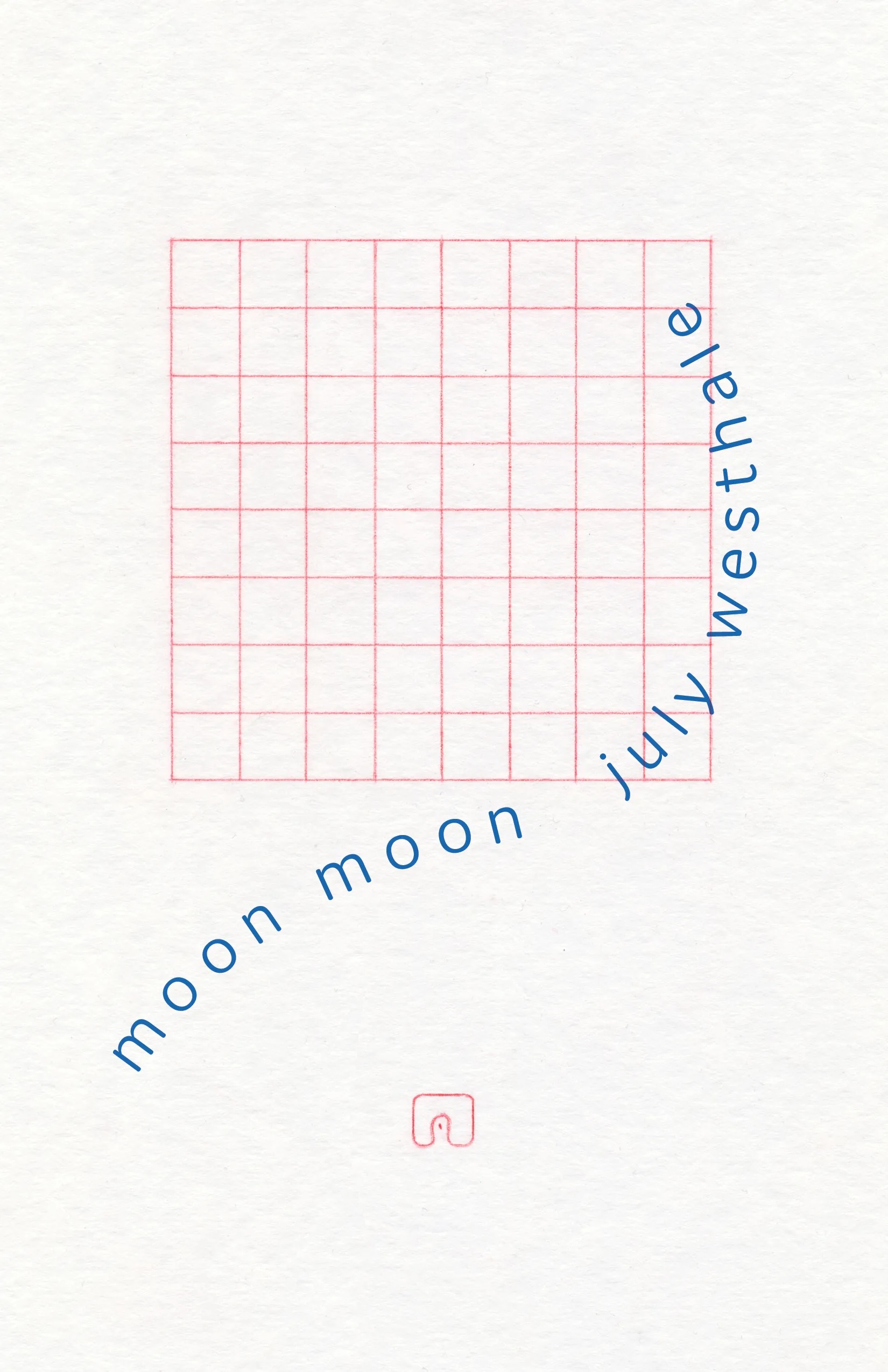

In poet JULY WESTHALE’s upcoming book, moon moon, humanity finds itself in a precarious position—Earth has become unlivable, forcing people to seek refuge elsewhere. But when the moon proves overcrowded, humanity pushes even further, settling on the mysterious and perhaps astronomically dubious moon’s moon. Part modern epic, part ecological elegy, the collection tackles eco-grief, climate change, and human hubris, all while weaving humor throughout its poetic narrative.

July Westhale, whose earlier books include the autobiographical exploration of class warfare in California, Trailer Trash, and the intense poetic meditation on desire and divinity, Via Negativa (praised as “stunning” by Publishers Weekly), brings their signature incisiveness and wit to this timely new work. They also released the recent Unmade Hearts: My Sor Juana, a delicious translation of the work of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

Today, Westhale converses with poet BOSTON GORDON, author of Glory Holes and the forthcoming Loose Bricks. Gordon, who also champions queer and trans voices through Philadelphia’s acclaimed “You Can’t Kill A Poet” reading series, guides this thoughtful discussion as they delve into meditations on writing, the moon, and what poetry teaches us about ourselves.

You can pre-order moon moon here.

Boston Gordon (BG): You are a longtime friend and one of my favorite people who has workshopped my work. I’ve read and loved all your books, and moon moon is my favorite of the bunch. I’m consistently impressed with your detailed style, how you make the most of craft, and how nothing feels incidental. What’s your writing and editing process like? Where do you write? How do you make your work come together?

July Westhale (JW): This is such a kind thing to say! I adore your work—the tenderness in Glory Holes knocks me out, and I’m thrilled your new collection, Loose Bricks, is coming out in May as well. It feels like a true gift to be in friendship—and poetry friendship—with someone you’ve known a long time, to get to bear witness to them grow as a human and as a poet simultaneously. What a joy.

To your point about moon moon—I am not typically precious about my work, but this collection holds a special place in my heart. I think my books tend to be pretty different from one another, but moon moon especially deviates. It’s almost science fiction-y. I was working on a novel and a screenplay while writing moon moon, and taking fiction classes, and that feels clear in the narrative structure.

As for writing and editing—I write voraciously, and across genres, but I tend to write in jags. Months at a time, and then pauses. I’m usually working on multiple projects at once, and I’m lucky that I often have deadlines that provide some shape and momentum. I’m a ruthless over-editor, since I’m such a lyric maximalist. Because of this, I allow myself to be very free while I write and edit later, after the poems have been in a literal or metaphorical drawer for a while. There’s some consideration of form while writing (since form is breath), but I tend to focus more on the poem’s content first, and edit for the intuitive shape or form later.

I write everywhere, anywhere. It’s helpful if there’s a window and a blank wall where I can pin things up and visualize them, but that’s a nice-to-have. I’m lucky these days, however, to have a beautiful office with a window. I’m in Tucson, so the window is full of birds year-round. This is a joy to me, and my cat, Pig, who is almost always on my lap while I write.

I’m very visual and also an obsessive systems thinker. I was almost a scientist, and my rent job involves a lot of architecture-building and project management. This serves me so well as a creative person! After I’ve written a fair amount into a project, I tend to print the manuscript out, index it thematically, and put those themes on the wall on index cards. This allows me to see what I’m working on and where I need to go next. I genuinely never know until I’m already at a point of no return.

BG: A question from one Sagittarius Moon to another: What’s your relationship with the moon like? How often do you find the moon coming into your writing?

JW: I love this question! Aside from this collection, the moon doesn’t come into my writing a whole lot. However, I do think about the moon as a beacon of human earnestness that I’ve taken on as a sort of ars poetica. Here’s the gist: every single person who has a phone probably has dozens, if not hundreds, of shitty photos they’ve taken of the moon. Maybe they’ve even sent them to other people or gone through and looked at them again later, but probably they haven’t. The photos aren’t the point; these photos are a kind of failure. They will never be the moon, they will never get close to capturing the feeling we get when we look at the moon. But the human earnestness, the desire to take a photo of it, is so beautiful. It’s so like poetry, like poetry or art’s failure to capture the specific thing itself (because the thing itself isn’t actually the point).

BG: What was the jumping off point when thinking about moon moons?

JW: It was 2020, we were all in deep lockdown, and no one was having a good time. I was living in my friends’ basement, and my partnership had completely unraveled. Our pod was also potty-training our friends’ kid, which, honestly, if you don’t have four adults who are home 24/7, how do you do this? The political climate was ruinous. Everything felt like it was at a fever pitch and a tipping point, and really, it was.

I decided to write a modern epic about space travel, but I wanted it to be about a place we didn’t know anything about, something that perhaps wasn’t entirely astronomically true (I’m interested in science and I’m interested in science that is also speculative, I also have a book called Occasionally Accurate Science). A moon is familiar to us; the moon of a moon is less so. If people had to leave Earth and the moon was full, and they ended up at the moon’s moon, doesn’t it also seem like a kind of bargain Ramada? Like a head gasket blew on the Grapevine, and now you’re at a Red Lyon in Bakersfield? I don’t know, but I was interested in playing with it!

BG: What were your influences at the time you were writing moon moon? Were there any books, poems, movies, or songs that were really with you while you wrote?

JW: I was coming off the tail end of touring for Via Negativa, and teaching a lot of ecstatic poetry classes, so I was reading a lot of Ross Gay (Book of Delights got me through 2020). But I was also in the middle of a two-year novel-writing program, and reading lots of amazing little novels that did tremendous things, like Denis Johnson’s Angels and Joshua Mohr’s Sirens. I was, and still am, forever learning from Pam Houston—the way she thinks about books as each having a “shape.” And I was re-obsessed with Robin Coste Lewis’ Voyage of the Sable Venus. Musically, I think this was the year that I really let myself start to fanboy about Carly Rae Jepsen, and I’ve never looked back.

BG: As a number one fanboy of CRJ, I fully relate. Do you know that she had a moon era herself for her Loneliest Time album and tour? Also, one time I saw her play outside at the Stone Pony in Asbury Park under a miraculous full moon, and she made sure to tell all of us to look at the moon!

JW: God, I didn’t know that, but you know, I’m not surprised. The world I want to live in is one where you, me, and Carly Rae Jepsen are all cosmically linked by the moon. Yes. Let’s live in that world.

BG: We poets always use white spaces, caesura, and line breaks (or the lack thereof) to add shape and meaning to our poems. You use some really interesting blank spaces in moon moon. For instance, in “how it is said the world began: evolution,” you have blank spots almost like a Mad Lib. And in “for times they think they hang the moon,” you have a large blank parenthesis at the end of the piece. Tell me about what using blank space in these creative ways means to you.

JW: I feel like my use of white space gets weirder with every collection. The honest answer here is that my relationship to white space and other breath-denoting devices (like punctuation) came from developing hobbies where breath is the focal point. Like meditation, sure. But have you ever gone scuba diving? In scuba, you use breath to try to achieve “neutral buoyancy,” which is when you are neither sinking or floating upwards. This buoyancy not only helps you go through your air tank at a decent clip, but it also serves as the way you move through the water without being terribly disruptive. You achieve this by using your breath strategically, and you use your breath strategically by paying attention to it.

Another way to understand these breath/ing devices is to teach poetry classes to non-poets, which I started doing during lockdown. Non-poets are my favorite kinds of writers to teach, because you need to justify everything—you might spend time going through every type of punctuation, and what it can do within poetry, how it breaks things, or adds guardrails to breath. This is so fun! I encourage you to try it. Also, justifying everything breaks you out of any bad habits you might have as a writer and teacher (like craft rules you don’t believe in). Lastly, the joke is always on everyone: non-poets are always poets all along.

BG: Repetition is such a useful tool in the poet’s toolkit. What were you thinking about repetition when you decided to focus on the idea of the moon’s moon throughout the book?

JW: Repetition has always been one of my favorite poetic tools! I love how it brings a sort of kinesis to a poem, which is often fun to read aloud (a nice perk), and I especially love the obliterating element of it. I experimented wildly with repetition in Via Negativa by having (mostly) poems that were titled one of three titles: Via Negativa, Ars Poetica, or Love Poem. Each time you repeat a name (like an ars poetica, or the moon of a moon), you are given the opportunity to overwrite the previous version of it. This feels so intuitive to the way I engage with poetry, which is to say, obsessively. These are all unanswerable questions, after all, with so many possible forking paths. Why not try going in all directions, holding space for them all, contradicting yourself, breaking the fourth wall, catching yourself in a lie, finding new truths? It’s how we think about truths and concepts intuitively anyway.

BG: The idea that we might someday need to leave our own planet has a long history. It feels more relevant than ever as climate change causes natural disasters to increase in both rate and devastation. What did you want to say in moon moon about uninhabitable places?

Light—moonlight, sunlight, artificial light—creates our external world and is always there, whether we notice it or not.”

JW: I’m from the American Southwest. I thought this book was a break from writing about California, and in a way it is, but in a way it’s not. It is still, at the end of the day, about both the speculation and known realities of living in uninhabitable places. Is the moon’s moon really that different from California? From Tucson, where I now live? It is, but only because it’s not a real place. The surreality or unreality of the place offers a lot of possibilities, however, that we don’t have here on earth. I don’t mean this in a “let’s go to Mars” billionaire sort of way—that is a philosophy of a people who have had the privilege of shooting their shots, who have a shoot and a shot at all. I mean it’s the same sort of possibility that we get through the obliteration of repetition.

And, of course, I wrote this in 2020, but you’re right that it feels even more timely now, and grossly, even more tongue-in-cheek, which isn’t what I wanted. Though I’m not surprised. I imagine we will continue to find new ways to engage with this narrative of space speculation and climate crisis.

BG: Is there a particular poem in moon moon that surprised you while writing or revising it?

JW: In the same vein as the above, I was surprised by the section where the heroes (formally known as “humans”) are on the moon’s moon. I knew, spatially, it would feel different—more isolated, more wildly speculative—but I was surprised to find myself writing “log from unknown hero, date rubbed off.” It felt like it stemmed from some deep part of my early childhood education, growing up in California, learning about the disastrous and terrible journey of the Donner Party. Which makes a kind of sense, really, that parallel. The thing that always struck me about the Donner Party is that they took the word of a man who had never taken the trip himself.

That whole section was perhaps my favorite to write, because it got to be completely conceptualized. It was completely up to my imagination, and the imagination of the “heroes,” and by the third part, we start to wonder if the entire thing wasn’t just imagined.

BG: When I saw the 2024 total solar eclipse last year, I became utterly obsessed with the sun in all the writing I did for months. Do you think it’s only natural, as writers who spend so much time looking inward—looking at our relationships, our histories, our families, our beloveds—that we eventually need to crane our necks up to the heavens to imagine what’s going on up there?

JW: Yes! I think this is a similar impulse that drives us—not just writers, but humans—to take shitty phone photos of the moon. There’s an earnestness to it, or maybe an externalization. There’s also a craft to it, in addition to the existential; in fiction, you hear people ask a lot, “What is the light doing?” Light—moonlight, sunlight, artificial light—creates our external world and is always there, whether we notice it or not.

BG: Can you share something unexpected you learned about yourself through writing poetry?

JW: God, I feel like everything worth learning about myself I learned through poetry, but I think perhaps the most unexpected thing is this: my capacity for unanswerable questions is limitless. The answer isn’t the point; the many answers, the multiplicity of answers, what Keats called negative capability (the ability to sit in uncertainty without reaching for fact), is the key that unlocks truth and beauty. This has been one of the things in my life that has allowed me to access joy and to write, even in the darkest times, because it means being in full presence with the world without attaching to the truth of it.

Poet and translator July Westhale was born in the American Southwest. Their books include moon moon, Trailer Trash, Unmade Hearts, and Via Negativa, which Publishers Weekly called “stunning” in a starred review. Ocean Vuong chose Westhale as the 2018 University of Arizona Poetry Center Fellow. Their translation of the Chilean poet Rolando Cardenas’ collected works was selected for the 2026 Unsung Masters Series (forthcoming from Pleiades Press). They have work in McSweeney’s, DIAGRAM, The National Poetry Review, Prairie Schooner, CALYX, Hayden’s Ferry Review, and The Huffington Post, among others. July is represented by Carolyn Forde at Transatlantic and lives in Tucson, where they are adapting their novel to film.

Boston Gordon (he/they) is a gay transgender poet from Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He is the author of the chapbook Glory Holes, from Harbor Editions. His first full-length book, Loose Bricks, will be published in May 2025. He runs the You Can’t Kill A Poet reading series—which highlights queer and trans identified writers in Philadelphia. He has poems published in many places like Guernica, American Poetry Review, and Best New Poets.