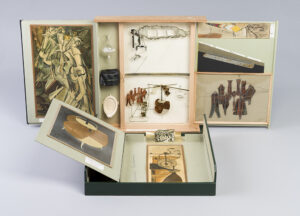

PARTIAL VIEW OF RESTORED HARRISON BOÎTE. MARCEL DUCHAMP (AMERICAN 1887-1968), BOX IN A VALISE (BOÎTE-EN-VALISE) FROM OR BY MARCEL DUCHAMP OR RROSE SÉLAVY, 1963 (SERIES E ). CINCINNATI ART MUSEUM: GIFT OF ANNE W. HARRISON AND FAMILY IN MEMORY OF AGNES SATTLER HARRISON AND ALEXINA “TEENY” SATTLER DUCHAMP, 2016.305 © ASSOCIATION MARCEL DUCHAMP / ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY / ADAGP, PARIS 2023. IMAGE COURTESY OF CINCINNATI ART MUSEUM, PHOTOGRAPHY BY ROB DESLONGCHAMPS

“Everything important that I have done can be put into a little suitcase.”

—Marcel Duchamp, Life magazine, 1952

For many years I hardly told anyone that my grandmother’s sister Teeny was married to Marcel Duchamp, and before that to Pierre Matisse, the art dealer son of Henri. Friends I’ve known all my life have stopped me in disbelief when these facts have come up in passing—a disbelief arising not from the facts themselves but from my never having shared them. The first time I ever mentioned the connection to anyone outside the family, I was in college, sitting in the Hungarian Pastry Shop on Amsterdam Avenue with my professor, the poet David Shapiro. “Wait,” he said, “Teeny Duchamp is your great aunt?!” I was surprised he knew exactly who she was.

My reticence came naturally: my family didn’t make much of such things when my siblings and I were growing up, and our parents weren’t exactly devotees of the modernist avant-garde. From time to time, our grandmother Agnes (we called her Aggie) would refer to “Teeny and Marcel,” but without explaining that Marcel was a well-known artist. And even later, after I did know that, and knew Teeny herself, I rarely mentioned the relationship. That changed in 2016 when I took on a six-month project involving a work Duchamp had given my grandparents, one of his Boîtes-en-valise, or Boxes-in-a-suitcase. I just didn’t feel right not mentioning it when someone asked, “What have you been up to?”

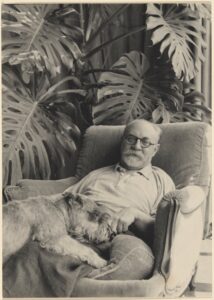

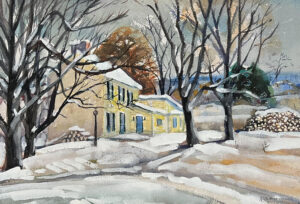

Growing up, I gradually became aware that, among my grandmother’s own paintings of barns and Ohio landscapes hanging on the walls of my grandparents’ old farmhouse near Cincinnati, a handful of significant artworks were also on display. Several of these, I later learned, were acquired from the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York. One was a pre-Columbian stone mask with deep, shadowed eye sockets that stared out spookily into the living room from the wall above the blue sofa. From the ceiling in the same room hung a playful mobile by Alexander Calder, under which we all sang carols every Christmas Eve. When my father was a boy, he and my grandfather had had contests shooting at it with rubber-band-powered BB gun pistols, chipping the paint off its goofy-shaped metal fins. In an act of naïve restoration, my grandmother repainted it, putting a further dent in its value. A painting by the Chilean surrealist Roberto Matta hung over the fireplace, but my grandfather hated it, quipping, “It doesn’t really Matta,” and they eventually sold it—spurred perhaps by the fact that Pierre Matisse left Teeny, in 1949, for Matta’s second wife.

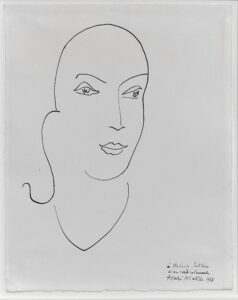

HENRI MATISSE, TEENY, 1938, PRIVATE COLLECTION © ARCHIVES HENRI MATISSE

There was also an exquisite India ink line drawing of Teeny by Henri Matisse, from 1938, inscribed to her father Robert Sattler, a prominent eye surgeon. It hung outside my grandparents’ bedroom door in a bamboo frame. I remember my grandmother showing me, long before I knew who Matisse was, how he had drawn the mouth with one graceful line that traced the rising and falling contour of the upper lip, made a hairpin turn to depict the shallow curve between the lips, then looped back again to follow the bottom edge of the lower lip.

Duchamp gave my grandparents the Boîte-en-valise in the early 1960s. It was one of many handmade boxes Duchamp created containing miniature versions of his paintings and other works. This item, with its resemblance to a children’s boxed game, might have been the most intriguing to my siblings and me, but it was delicate, and we weren’t allowed to play with it.

When my grandmother died in 1986, these artworks were passed down to my father, his brother, and his sister. Since my father wasn’t interested in art, and my mother, as an in-law, thought she should stay out of it, he let his siblings have their first choices. That’s how my parents ended up with Duchamp’s Boîte. At first, they treated it with indifference, even mild disdain—a “what the hell is this thing?” attitude. My mother clearly would have chosen the Matisse drawing of Teeny, which could be hung on a wall and appreciated… whereas the Boîte needed to be carefully opened and set up to be viewed—and what were all those strange items inside? Baffled, they stashed it under one of the beds in my brother Jeremy’s old room.

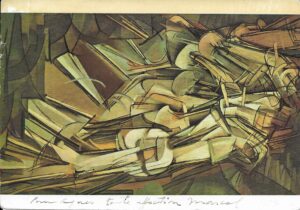

Duchamp first conceived the idea of the Boîte-en-valise in the early 1930s, though at first he wasn’t sure what form it would take. He intended it to be a kind of catalogue of his major artistic creations, though not in the traditional format of a book. Early on, he referred to it as his “album project,” a phrase that conjures a photo album, as though his paintings and other pieces were members of his family. He eventually decided the reproductions would be housed inside a box that could be opened up and explored, like a miniature art gallery. Between 1935 and 1940, Duchamp worked painstakingly on fabricating the replicas of sixty-nine of his artworks, an endeavor that was much more complicated, time-consuming, and revolutionary than it seems to us nowadays, when we have numerous ways to easily reproduce images and objects. The copies included small-scale versions of his best-known paintings, like Nude Descending a Staircase, which had created a sensation in the 1913 Armory Show; some of his “readymades”—everyday, manufactured objects (like a snow shovel or his infamous urinal entitled Fountain) that were contextually transformed into works of art simply by having been chosen and presented by the artist; and a number of less classifiable pieces. One of these was a replica of the complex and enigmatic glass work called The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (a.k.a. The Large Glass), which Duchamp fashioned out of clear celluloid, meticulously depicting even the cracks formed in the glass when the original was accidentally shattered. On three separate trips from Paris to Marseilles, Duchamp smuggled these components out of the Nazi-occupied zone of France, using a card identifying him as a cheese merchant, and in spring 1942 he booked passage to Casablanca and then to New York.

In the end, the box was made of cardboard encased in a leather valise and lined on the inside with colored paper, and there were some wooden structural elements and tracks for panels that could be pulled out, as well as a further enclosure that opened like a cigar box to reveal a neat pile of reproductions fastened to black construction paper. Though the boxes were commonly referred to as the Boîtes-en-valise, the actual title was de ou par MARCEL DUCHAMP ou RROSE SÉLAVY, the latter name (containing a pun on “C’est la vie”) referring to the female alter ego Duchamp had invented for himself around 1920. Only the first series featured the leather suitcase-like exterior; Duchamp gave many of these to friends, often well-known figures in the art world (the first went to Peggy Guggenheim). Subsequent editions, often referred to simply as Boîtes, since they didn’t include the valise, were covered in varying shades of imitation leather, and the color of the interior lining also varied. The one Duchamp gave to my grandparents was from the fifth of seven series, dated 1963, and has a dark green faux-leather exterior and pistachio-green paper lining the inside. At that point Duchamp was still overseeing the project, but Teeny’s daughter Jackie Matisse Monnier was assembling the individual Boîtes.

TEENY AND AGNES AS GIRLS, PROBABLY OHIO RIVER, CINCINNATI, OHIO

I never met Duchamp—I was ten years old when he died in 1968. What little I heard about him from the family had less to do with his art than with his personality: his charm, his sense of humor, his inventiveness, his intelligence worn lightly, his lack of egotism, and his proficiency at chess. Everyone seemed to like him. Even my father, who wasn’t a fan of artsy types and looked on with dismay, and the occasional barbed remark, as one of his sons became an artist and another a poet, had good things to say about Marcel. As a young businessman, my father told me, he had stayed with Teeny and Marcel during a trip to New York, and he described Marcel as friendly and easy to talk to.

“But what on Earth did you talk about?” I asked.

“Mostly baseball,” he replied.

JEFFREY HARRISON, CHAMBRE DE BONNE VIEW, 1979

Jackie and Teeny came into my life in 1979, slightly over a decade after Duchamp’s death. In a way, I have the French poet Pierre Reverdy to thank. Between my junior and senior years at Columbia, I received a summer grant from the college to study revision in Reverdy’s poetry at the Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève in Paris (where Duchamp had worked in his twenties, though I didn’t know that then). I stayed in a chambre de bonne (maid’s room) on the top floor of Jackie’s building on Rue du Bac. My spartan room overlooked the courtyard and had a view above rooftops of the Eiffel Tower in alignment with the classical dome of Les Invalides. Only years later did I learn that in the sixties this room had been Jackie’s studio, where she assembled the last several series of Boîtes, including the one my parents came to own. A flight of service stairs led to a back entrance of the Monniers’ apartment, and I could go down to take a bath, chat with Jackie, or borrow books from her shelves. I remember reading John Cage’s Silence and jotting sentences from it in my notebook like, “Beauty is now underfoot wherever we take the trouble to look,” which felt like a creed to live by. In August my girlfriend Julie joined me, and we stayed on to take the fall semester at Reid Hall, Columbia’s program in Paris. We cooked on a single-burner hotplate, but Jackie regularly invited us down to dinner with her family. One entire wall of the dining room was taken up by a large mixed-media assemblage by Jackie’s friend Niki de Saint Phalle, a kind of ungodly altarpiece encrusted with toy bats, rats, guns, religious symbols, and various other figurines, all painted gold—much more menacing than the whimsical, colorful, and buoyant figures this artist would become best known for. Julie and I often went to see Teeny at her house in the village of Villiers-sous-Grez, near Fontainebleau, sometimes driving with Jackie and sometimes taking the train.

Teeny’s house felt like a magical place. From the street it didn’t look like much—just one long stucco wall that went right up to the next house on a narrow village street. But, once the wooden double doors opened, the entryway led into an open courtyard shaded by two big horse chestnut trees, around which the old farmhouse was arranged. Meals were often served at a table in the courtyard. It was there that Julie and I had our first really good beet salad and learned what real, homemade mayonnaise tastes like. On the far side of the courtyard, behind the back section of the house, a progression of widening spaces opened up: a terrace, then a garden, then an orchard, and beyond the orchard expansive wheat fields studded with red poppies in summer, the even wider sky opening above. Julie and I usually stayed in a garret-like room in the back of the house, whose downstairs featured a blue bathtub shaped like a hippopotamus made by the sculptor François-Xavier Lalanne. Great twentieth-century artworks appeared all around the house but somehow felt natural in the simple rooms: a Fauvist seascape by Matisse, Man Ray’s Indestructible Object (a wooden, pyramidal metronome with a small photo of an eye attached to the metal pendulum that swings back and forth), an elegant yet playful wooden sculpture by Brancusi entitled Sophisticated Young Lady, a version of Duchamp’s “assisted readymade” consisting of a bicycle wheel mounted on a stool, and his Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy?, a small birdcage filled with blocks of marble that looked like sugar cubes, with a thermometer and cuttlefish bone angled through the bars.

We were always missing someone like John Cage or Merce Cunningham by a day or two. We did meet Dorothea Tanning, the surrealist painter who had been married to Max Ernst and who was largely responsible for bringing Teeny and Marcel together. One of the first times we visited, Teeny picked us up at the train station wearing leather pants, explaining she had stayed up all night dancing at a club with Jasper Johns. She was seventy-three at the time.

MAN RAY, “MARCEL DUCHAMP ET ALEXINA DUCHAMP,” PARIS, 1954–55 © MAN RAY 2015 TRUST / ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY / ADAGP, PARIS 2023

Teeny welcomed us immediately. Because she and I had both grown up in Cincinnati (albeit two generations apart) and had relatives in common, there was a natural connection between us that, for her, went back to the period of her life pre-dating her adventures in the art world. At the same time, she was part of an artistic community that intrigued Julie and me. Sometimes we went on excursions together, to see the rock formations in Fontainebleau Forest or visit the nearby chateau, but often we just hung out at her house and talked—about art, poetry, memories, all sorts of things. She had a genuine interest in what we were studying (Romanesque and Gothic architecture, French film, the poetry of the French surrealists), as well as in my endeavors to write poems, though I didn’t show her any of my attempts for a couple of years. I didn’t ask her about Duchamp directly, but sometimes she’d reminisce about him. I remember her saying he never let negative criticism bother him at all, which impressed me.

These were days steeped in family and art, in the beauty and pleasures of France, days which, though we didn’t know it then, Julie and I would carry with us through decades of marriage together.

A story I wish I could tell Duchamp: In the mid-eighties, when my brother Jeremy was in graduate school in printmaking, he had to write a paper on Duchamp’s readymades for an art history class. I told him to photocopy a chapter of a book or an article on the readymades, and title it “Readymade Paper on Duchamp’s Readymades.” He did that, waiting until the next day to turn in his “real” paper. The professor thanked him but also commented that the first paper would have been sufficient.

Teeny reminded me of my grandmother in certain ways—the plain Midwestern accent, the strong facial resemblance, and some of her mannerisms—but she was also different. Teeny (whose nickname came from her small size as a baby—her given name was Alexina) had straight hair that she wore in a fashionable bob, whereas Aggie’s hair was curly and coiffed more conventionally for someone of her age and generation. Teeny was also warmer, and had a little more verve, a more highly developed sense of fun, and less of an irritable edge. The two had also made very different choices in how to live their lives: Agnes had stayed in provincial Cincinnati, whereas Teeny couldn’t wait to get out of there, and she became part of a larger, more cosmopolitan world. My grandmother did not admire what she called pseudo-intellectuals, pronouncing the first syllable of that term like the word suede. Teeny was often surrounded by intellectuals and artistic types, but she was never pretentious, in much the same way she was fluent in French but spoke it with an American accent she didn’t attempt to disguise. And although she’d left Ohio far behind, she never forgot her roots there. During one of our visits to Villiers in the eighties, she recited a haiku-like poem she had written at twenty, which I jotted down into my notebook:

Hard clay, the earth,

ironweed and corn—

that was my crib.

This was the landscape in which the sisters had grown up, and which Aggie continued to record in paintings that my cousins, my siblings, and I now have on our walls. It’s too easy to say Teeny was the sophisticate and Agnes the yokel, or that Agnes became a Sunday painter while Teeny married into great art. They had both grown up in a household steeped in European culture—their father’s parents were German and Austrian, and their mother had spent much of her childhood in Italy—and they both left Cincinnati in their teens to study in Paris, Agnes going first and her younger sister following. But Agnes also came back first, returning to Cincinnati, Teeny told me, to become a debutante, and then to marry my grandfather. Teeny stayed on in France for several years, an immersion that set the trajectory of her future. She took art classes in Vienna and studied sculpture in Paris with Brancusi, whom she met through friends of her mother’s, and, at the age of sixteen, she briefly met Duchamp, a full three decades before she married him.1

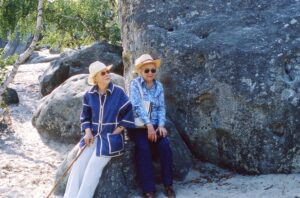

BARBARA SCHUMACHER, AGNES AND TEENY IN COURTYARD, VILLIERS-SOUS-GREZ, FRANCE, 1983

BARBARA SCHUMACHER, TEENY AND AGNES IN FONTAINEBLEAU FOREST, 1983

After my grandfather died in 1980, Aggie began making more trips to see Teeny in France. I think they had a lot of fun together during those years, while occasionally engaging in sisterly sparring that probably went back to when they were girls. Teeny’s live-in helper Jacques described the two of them sitting at either end of the table in the courtyard, both wearing wide-brimmed straw hats, their crossed legs propped on the table, drinking whiskey “like cowboys,” each with her own bottle—Old Grand-Dad bourbon for Agnes, and Jack Daniels for Teeny—each remarking to the other, “How can you drink that stuff?” One night, they were watching a French movie on TV—something from the New Wave, possibly by Godard. Frustrated, unable to follow the film, Aggie announced she was going to bed. Teeny’s response: “Can’t you just enjoy it without understanding it?”

That’s a question I might have asked my parents in regard to the Boîte. You didn’t need to be an art historian to see how amazing it was.

My parents’ initial reaction to the Boîte wasn’t entirely surprising, though. Characterized by his biographer Calvin Tomkins as “the least understandable artist of our century,” Duchamp gave up painting in his mid-twenties and went on to push the boundaries of art well beyond conventional categories and mediums. The paintings from 1912 that Duchamp considered his best, like Nude Descending a Staircase, Bride, and The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes—all of which are prominently featured in the Boîte—were (I can hear my mother saying) weird enough, with their tangle of interconnected shapes resembling machine parts that were meant somehow to represent the human figure, but some of the works that followed might seem truly bizarre to anyone expecting anything remotely traditional.

MAN RAY, “MARCEL DUCHAMP, ALEXINA DUCHAMP JOUANT AUX ÉCHECS À CADAQUÉS,” 1968 © MAN RAY 2015 TRUST / ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY / ADAGP, PARIS 2023

Julie and I, however, were fascinated when we went through the Boîte while visiting my parents in Cincinnati not long after my father inherited it. By this time, we had gotten to know Teeny, and we had both studied art history in college (Julie had majored in it). We had married several years earlier, and now Julie was in architecture school, while I was publishing my first poems in literary magazines and working at The Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, where several old letters from Marcel Duchamp to the pioneering modern art collector Duncan Phillips crossed my desk in the research department.

The box itself was a little larger than I recalled—about fifteen by fifteen inches, and slightly over three inches deep. Its dark green faux-leather exterior was scuffed in places but in pretty good shape. A wide surface is needed to open and set up the Boîte, and, as I remember, we chose the kitchen table my mother had painted red, with blue curlicues around the edges, where we’d all had breakfast growing up. Opening the box was a little tricky, we rediscovered: to avoid stressing the hinges, you had to pull the lid partway up, then lift the interior wooden structure upright while pulling the lid back to lie flat on the table. There, nestled in a recess on the left side of this central vertical structure, were replicas of three of the readymades: a teardrop-shaped pharmacist’s ampule or vial (50 cc of Paris Air, 1919), an Underwood typewriter cover about the right size for a dollhouse (Traveler’s Folding Item, 1917), and a tiny urinal representing the full-sized one that caused a stir in 1917 when Duchamp submitted it to a group show under the pseudonym R. Mutt (Fountain). To their right, taking up most of this main structure’s space like a two-pane, floor-to-ceiling window in an architectural model, was the celluloid replica of The Large Glass, often considered Duchamp’s most significant work. When we pulled the left panel out, there was Nude Descending a Staircase, then, when we unfolded the panel at its hinge, Bride and The King and Queen Surrounded by Swift Nudes, each of these paintings framed with narrow strips of wood. (Labels for each work, with titles, dates, and dimensions, enhanced the impression that we were visiting a miniature museum.) The right panel, when pulled out, displayed the image of a metal comb, one of Duchamp’s readymades; another miniature and complicated painting (Tu m’, from 1918); and a replica of a preliminary glass study for part of The Large Glass (9 Malic Moulds, 1914–15). Only after we’d pulled both panels out was The Large Glass fully visible, with its cryptic, mechanical-sexual iconography I don’t pretend, even now, to understand.

A couple of other miniature works occupied niches around the edge of the Boîte’s bottom, horizontal half, including a pop-up version of Why Not Sneeze Rose Sélavy?, the birdcage full of faux sugar cubes. But most of the space in the lower part of the box was occupied by a compartment whose lid lifts up to reveal a stack of large, double-folded sheets of black paper with reproductions attached to each of their four surfaces. Among them, we found L.H.O.O.Q., the postcard of the Mona Lisa that Duchamp had irreverently altered by adding a goatee and mustache, and the red and blue, optically vibrant Fluttering Hearts, on whose label he had inscribed the Boîte to my grandparents: To Agnes and Carl / grande affection / Marcel Duchamp.

MARCEL DUCHAMP, FLUTTERING HEARTS FROM HARRISON BOÎTE © ASSOCIATION MARCEL DUCHAMP / ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NY / ADAGP, PARIS 2023 PHOTOGRAPH BY JEREMY HARRISON

I can’t remember if my parents were in the room with us, but I imagine them standing behind us, making comments on how strange everything seemed and asking questions about what it all meant, my mother laughing in surprise when she saw the urinal. There would have been at least one painting by my grandmother on the wall in that room, depicting the nineteenth-century brick house we were now in, hovering around this work of art that Aggie had passed on to us. With the panels pulled out and the various reproductions arrayed around the main apparatus, the whole thing looked like a model of a stage set for an experimental theater troupe, a diorama for a school science project made by the class genius, or an elaborate three-dimensional board game whose list of arcane instructions had been misplaced.

The problem was that some of the reproductions were coming unglued from their backing, and the panels, which didn’t slide in and out very easily on their wooden tracks, made us anxious about causing further damage. I must have written Teeny about it right away, as a letter from her dated October 1986—mostly about how much she missed Aggie, who had died in June—says: “I am glad you have the Valise. Jackie used to put them together, and I know the awful problems of things getting unglued.” She added that Jackie would be in touch about what to do. I can’t remember (and now can’t find) Jackie’s instructions, but as a family we came to a tacit understanding that, as much as possible, it was best to leave the Boîte alone, putting off questions about its future until one of us had more time to address them. This turned out to be quite a while. Apart from rare occasions during holidays when we opened it up to explore its contents again, for almost three decades the Boîte lay hidden under my brother’s bed, a half-forgotten treasure.

I’m not sure what Duchamp would have thought of our worries about damaging the Boîte. He handles the Box itself and the items inside rather nonchalantly in a 1956 interview that can be found on YouTube. He was also famously unfazed when his major work, The Large Glass, was shattered in its crate while in transit, and he claimed to love the pattern of the cracks once he painstakingly put it back together. In a taped interview from 1959, he actually breaks into giggles while recounting the story of the accident.

I had always meant to “do something” about the Boîte, but apart from getting it repaired, what that something was remained obscure, like an unfinished thought dwelling in a murky region of my mind, coming to the surface only now and then as Julie and I made a life together, pursued careers, moved several times, and raised a son and a daughter. It wasn’t until June 2016, thirty years after my father had inherited it and four years after his death, that I began to address the question of what the family should do with the Boîte: keep it, restore it, sell it, give or lend it to a museum? I first brought this question up with my mother, now the owner, and then with my brother Jeremy and my sister, Ellen.

There was only one problem: the Boîte was no longer under Jeremy’s bed. In fact, there were no longer any beds in that room: by this time Ellen was living in our parents’ old house in the country, and those twin beds had been moved to the guest room of my mother’s new house. And the Boîte was not under either of them. So, where was it? My mother couldn’t find it. My sister couldn’t find it. Eight hundred miles away in the Boston area, I was getting nervous. Like our father, my sister had a yen for throwing things away, and there had been a great purge after she moved into our childhood house. I remembered seeing the growing tumulus of debris in front of the garage before the garbage collectors hauled it away, and I had frightening visions of the Boîte atop a dumpster full of trash or buried in a landfill.

Ellen finally called, after about a week, to tell me she had located the Boîte. This was a huge relief, though it worried me that she’d found it in the attic, where the extreme temperatures in winter and summer couldn’t have been good for it. God knows how long it had been up there—at least a couple of years, since our mother had moved out of the house. Still, we had it again. The next step was to seek advice from experts—as many as possible, I felt, since we wanted to know all our options and make the best choices. I started by contacting my cousin Antoine, Jackie’s son, to whom she had passed on the duties associated with Duchamp’s legacy. Julie and I had gotten to know Antoine during the summer and fall of 1979, when we were living in Jackie’s building, and we had borrowed some of his Velvet Underground albums and played them on a child’s simple record player in our chambre de bonne.

Antoine put me in touch with Ecke Bonk, who probably knew more about Duchamp’s Boîtes-en-valise than anyone. I had met Ecke in 1987, when Julie and I attended a Duchamp conference at the Philadelphia Museum of Art that Teeny and Jackie had flown over for, and I owned a copy of his exhaustive book Marcel Duchamp: The Box in a Valise. Among other suggestions, he advised having a museum-caliber paper conservator restore the Boîte. Ecke’s view seemed in harmony with my main goal: to do what was best for the Boîte itself. Restoration, he added, would also increase its value.

It was the week-long scare when the Boîte went missing that, for me, tipped the balance toward giving the Boîte to a museum. That way, I reasoned, the Boîte would be stored in a climate-controlled environment and cared for by professionals. The Cincinnati Art Museum—if they were interested in it—would be the obvious choice, since the city had been the home of our Boîte ever since Duchamp had given it to my grandparents. My brother and sister liked the idea right away, while our mother needed a little more convincing, especially when she heard from her accountant that the resulting tax break would amount to only a third of the Boîte’s value. I pointed out that the deduction might still be significant, and besides, the gift would be an enduring legacy. She came around but couldn’t help remarking, “You know they’re just going to keep it in the basement. That’s what they always do.”

“Well,” I replied, “at least it’ll be safe there, as opposed to under Jeremy’s bed.”

“Actually,” she countered, “conditions under that bed were not so bad.”

In July, I flew to Cincinnati to drive my mother up to our family’s summer place in the Adirondacks. The Boîte would be going with us, so I could later take it to Boston and then (though I didn’t know this yet) to New York. I swaddled it in bubble wrap and packed it in a cardboard box in preparation for the trip. On the morning of our departure, I found a safe place for it in the back of my mother’s blue Subaru, among our luggage, bags of food, bales of paper towels and toilet paper, a case of my mother’s favorite sauvignon blanc, and other supplies—an extraordinary object nestled among ordinary things. That night, I took the box-within-a-box into our hotel room, placing it on the little breakfast table next to a plastic potted fern that could have been a readymade awaiting its clever title. “I bet we’re the only people in this hotel with a priceless work of art in their room,” my mother joked as she unpacked her bag.

Once we were settled at the lake, I got in touch with Anne Goodyear, a Duchamp scholar and the co-director of the Bowdoin College Museum of Art, to whom I’d been introduced by my friend Charlie Brock, a curator at the National Gallery who had been one of my colleagues at The Phillips Collection decades earlier. Anne’s enthusiasm was audible even over the fickle, crackling landline we have up there. She seemed to know everyone in the Duchamp galaxy, and she suggested a few paper conservators we might consider using, as well as other specialists. Calling the Boîte “a canonical object,” a major work by a major artist—rather than a minor side project, as it might originally have been seen—she was thrilled to hear we wanted to give it to a museum, and she talked me through some of the logistical steps a donation would entail. Anne would become my main advisor, guiding me through every phase of the project from that point forward.

One evening I unpacked the Boîte to show it to our twenty-something son and daughter and their cousins, spreading it out on the large art table on which they, as well as my siblings and I, had all drawn pictures and done art projects as children. With its pine-green exterior and the earth tones of many of the reproductions inside, this complicated modernist object somehow felt completely at home among the cabin’s fraying rattan furniture, Navajo-style rugs, and the shabby moose head that gazed down amiably at our family group.

I followed Anne’s leads over the next few months, gathering as much information as I could. The conservator whose name kept coming up was Scott Gerson, who had worked for the Museum of Modern Art but now had his own studio in New York. When I reached him in mid-October, I was surprised to hear he already knew about our Boîte: word had traveled from my daughter, Eliza, who currently had an internship at MoMA, through one of Scott’s former colleagues there. Scott had restored a number of Duchamp’s Boîtes before, including some owned by MoMA, so he had direct experience, unlike some of the other conservators I’d been in touch with. We made plans for me to drive the Box to New York later that month.

I briefly worried about whether to insure the Boîte for the drive down, since my research had made me more aware of its approximate market value—a concept Duchamp might have had some mixed feelings about, since he frowned on the commercialization of art and, in his lifetime, took steps to keep the prices for his own works from getting too high. Now, however, decades after his death, he was so well-known that any little thing he’d had a hand in, like an invitation he’d designed for the opening of an art show, was worth something. In any case, insuring the Boîte would entail having it appraised first, and I hadn’t gotten to that stage yet. When I asked my cousin Paul Matisse, Jackie’s brother, he said not to bother with insurance but to do what his mother, Teeny, always did and “trust in the guardian angels of art.” After all, I had driven the Boîte up to a remote lake in the Adirondacks, and then to Boston, without insuring it. In fact, I don’t think it had ever been insured. And besides, if something happened to it, an insurance claim wasn’t going to bring it back.

Julie and I had first met Paul at Teeny’s in the 1980s, but once we moved from Washington, DC, to Connecticut in the early nineties, with one small child and another on the way, and especially after we moved an hour away from him in Massachusetts in 1997, he and I began to spend more time together. It was as though I’d pulled out another panel of the metaphorical Boîte that represented this side of my extended family. Over several decades, Paul and I became close friends, not letting our twenty-five-year age difference get in the way.

Paul lives in a big white former New England church he converted into a house that is, in its own way, as magical as Teeny’s. This is largely due to the presence of Paul’s amazing artwork-inventions, which he makes in his shop on the lower floor of the church: large, sleek, cylindrical aluminum bells that ring in deep, rich tones for many minutes before fading out completely; meticulously crafted kinetic sculptures that spin in unpredictable ways; and several kalliroscopes, an invention of Paul’s in which, under a glass pane, millions of tiny, light-reflecting crystals are suspended in a liquid of precisely the same density, so that the crystals never settle to the bottom but instead shift constantly, and beautifully, like liquid silk.

I had known about kalliroscopes since boyhood: my grandmother owned one of Paul’s large ones that hung on the wall, and she gave pocket-sized versions to my brothers and me. You could spin them on a little disk of ball bearings and watch the liquid swirl and shimmer, then slowly go still but continue to glimmer softly. After our mother found out the liquid inside was toxic, she worried that we would break the kalliroscopes and asphyxiate ourselves, and eventually, I think, she threw them away—in any case, they disappeared. (Every now and then one shows up on eBay.)

Despite his marvelous works, which can be found all around the world in museums, sculpture parks, or public spaces, Paul has never called himself an artist. He explained that that role in his family was already fully occupied by his grandfather Henri Matisse, and those who followed were discouraged from artistic pursuits.2 Perhaps by calling himself an inventor Paul freed himself from a certain pressure that comes with the label “artist,” not to mention the name Matisse. This would put him in alignment with his stepfather Duchamp, who, as Calvin Tomkins explains, was interested above all else in “freedom—complete personal and intellectual and artistic freedom.” Duchamp too was a kind of artist-inventor, an explorer of ideas, and a searcher for new ways of doing and making things, and I believe he became an example for Paul, who is always engaged in some interesting problem he wants to work out, or pondering concepts like chaos theory or the invention of the musical scale. I imagine Paul felt, in Marcel’s company, as though he had access to a second mind enhancing his own—which is exactly how I’ve often felt when I am with Paul.

When I met Scott Gerson at his studio in Chelsea, he was at once easygoing and professional. The studio was a large, open room with shelving and flat files on the sides, print baths at one end, a number of worktables in the middle, and a wall of warehouse-style windows at the far end. The overall feel was of light and space, with white dominating, except for the area around Scott’s desk in a far corner, near the windows, where an impressive shelf of art books provided a colorful contrast. An assistant was sitting at one of the tables, working on a leafy plant drawing by Ellsworth Kelly.

Scott carefully unpacked the Boîte on a worktable and went through it, pointing out structural and other problems. Some were obvious—the reproduction of the painting Bride was completely detached from its panel—and others less so. Many of the issues he had seen while working on other Boîtes, and he said the restoration would be fairly straightforward. The only structural change he would make, he explained, would be to reattach the reproductions with paper hinges, which would clearly be an improvement over the original glue.

I finally spoke with the director of the Cincinnati Art Museum, Cameron Kitchin, in early November. He seemed excited about the possibility of the donation but also told me—for the sake of transparency, he said—that another Duchamp Boîte, owned by a Cincinnati collector, had been mentioned as an eventual gift to the museum. He wondered how we felt about that, and actually, I wondered how he felt about it, specifically whether the prospect of receiving this other Boîte in the future made him less interested in ours. He said he would talk to the collector and try to get “more clarity.” I suggested he find out which series the other Boîte was from, because all seven of the series were different, and there was a precedent, I knew from my research, for museums to own examples from more than one. Near the end of the conversation, he mentioned that the museum’s curator of prints and drawings happened to be in New York at the moment, and he asked if we could arrange for her to stop by Scott Gerson’s studio to see our Boîte. That seemed promising, though the information about the other Boîte left me feeling a little uneasy about whether the donation would even be possible.

Despite these doubts, I moved on to the next step in the process: finding an appraiser to calculate the value of the gift. When Paul Matisse called me to catch up and lament the election of Donald Trump days earlier, I mentioned my search, and he offered to put me in touch with his contact at Christie’s for the appraisal. Very soon I was on the phone with Jonathan Rendell, who I only later realized was the second-in-command at Christie’s Americas. An affable, somewhat formal but not at all stuffy Brit, he informed me that not only would Christie’s do the appraisal but they’d do it free of charge, because I was part of “the family.” I said something like, “Are you sure? I’m really not a Matisse. Paul is my first cousin once removed.”

He laughed and said that was close enough, adding, “The family has been very good to us,” which sounded a little like a line from The Godfather.

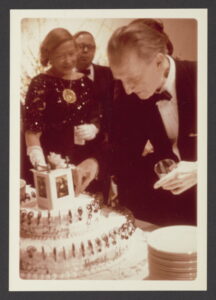

MARCEL DUCHAMP WITH L.H.O.O.Q. DECORATED CAKE AT PARTY FOR “NOT SEEN AND/OR LESS SEEN 1904–1964 OF/BY MARCEL DUCHAMP/RROSE SÉLAVY” EXHIBITION. 1965 MARCEL DUCHAMP ARCHIVES © ASSOCIATION MARCEL DUCHAMP, PARIS, 2022

The figure who loomed largest in “the family” was, of course, Paul’s grandfather Henri Matisse, whom Paul described as intense and driven compared to the casual and unhurried Duchamp (who was also a generation younger). Despite this difference in temperament, the young Duchamp was inspired by Matisse’s work, and Matisse was on the jury of the Salon d’Automne in 1908 when Duchamp’s paintings were first accepted. The two artists appeared together in the Armory Show of 1913, four decades before Duchamp and Teeny got together. Matisse had a close relationship with Teeny and was not happy when his son Pierre left her. Pierre, for his part, didn’t like Duchamp, “whose apparent lack of commitment to anything,” Calvin Tompkins tells us, “seemed to him highly irresponsible.” So it’s interesting that it was Duchamp who became Teeny’s second husband. It’s also interesting, though probably a coincidence, that Duchamp officially joined the family by marrying Teeny the same year that Henri Matisse died.

A few years before I started working on the Boîte project, in November 2011, Paul emailed me that he and his then-wife Mimi had attended a séance given by a medium “whose work it is to connect the shades of people who have died to their still-living relatives.” Mimi was so impressed by the young woman conducting the séance that she went back for her own private session. To Mimi’s surprise, the person who turned up from the other world on that occasion was Teeny, whom Mimi had never known. “There was a very clear connection between the two of them,” Paul wrote, adding, “Before Teeny faded away, the medium said she had said something about films, family films, and that Mimi should look for them.” He asked if I knew of any such films.

I remembered a couple of VHS tapes my uncle Lingy (my father’s older brother, no longer living at that point) had put together, made up of excerpts of old family movies taken by Aggie and Teeny’s mother. I told my sister where I thought they were stored—in the antique dry sink in our parents’ front hall—and asked her to mail them to me. Meanwhile, it turned out that Paul’s son George had copies of those same tapes, or some version of them. Soon we were all watching them and comparing notes. There was footage of Aggie and Teeny as young mothers, with Jackie, Paul, my father, and his siblings as babies and toddlers; of Jackie flying a kite (a foreshadowing of the kite-related artworks she would create much later); of my uncle Lingy, looking about twelve, riding a horse; and a playful sequence of my young grandparents spraying each other with a hose. A smartly dressed Pierre Matisse made a few brief appearances but never smiled or got sprayed with a hose. This was all amusing, but these scenes amounted to ordinary home movies, albeit very old ones. Surely Teeny’s spirit had been referring to something more significant.

I called my aunt Molly, Lingy’s widow, in Cincinnati, to ask if there was more film, and she said there were reels and reels of it—at least twenty—only a small fraction of which had been transferred to the VHS tapes. It sounded like a huge project to go through them all, but she was willing to let me borrow them. In the course of the conversation, she happened to mention, almost in passing, that, oh yes, there was also a small reel of film in a shoebox of Henri Matisse working on a mural—at his famous chapel in Vence, she thought. “Are you kidding?” I asked. She wasn’t. She also wasn’t sure what condition the film was in.

Our focus instantly shifted from the overabundance of home movies to this small film clip. I put Paul in touch with Molly, who agreed to send him the small reel. Paul then sent it to his son Michael in Seattle, who would digitize it. What they didn’t tell me until later (and I don’t think anyone ever told Molly) was that, despite having a tracking number, the package could not be traced for almost a week, and they feared the film had been lost. Perhaps the guardian angels of art (or maybe of film) had been careless… or perhaps they saved the day after all, because the package did finally show up. And several weeks later, Michael was emailing the digital version to all of us.

HENRI MATISSE AND RAUDI, THE MORGAN LIBRARY & MUSEUM. MA 5020. GIFT OF THE PIERRE MATISSE FOUNDATION, 1997 © ARCHIVES HENRI MATISSE

The film is from 1932, which apparently makes it the oldest known footage of Matisse at work by several decades. Only a minute or so long, it shows Matisse working not on the chapel in Vence, but on the first version of his mural The Dance, for the Barnes Foundation. (This version actually ended up in the Museum of Modern Art of the City of Paris. After working on it for a year, Matisse realized he’d gotten the dimensions wrong. Albert Barnes, who had already been hounding Matisse to get the mural finished, was infuriated when he heard the news.3) Matisse had rented a former garage in Nice to use as a studio, and the film shows him pointing things out with a long bamboo pole on the paper mock-up of the mural that takes up most of the wall on one side of the large room. He runs the pointer along the hip of one of the dancing figures, then aims it farther up, to the torso and thigh of another. Then he pushes a moveable set of stairs against the mural, locks the wheels, and walks up the steps to the top of the mural to make a small adjustment or show something to his audience of family members. A medium-sized schnauzer follows him up the stairs, and he pauses to pat the dog and kiss it on the head. Then he walks down the stairs, followed by the dog, walks a little farther, and does an about-face, causing the excited dog to go bounding up the stairs again, before running back down. The dog, who almost steals the scene, was named Rowdy, and was originally Teeny’s, but Teeny and Pierre had left him with his father while they went on their honeymoon, and Matisse had gotten so attached to the dog, whose name he’d Frenchified to Raudi, that he insisted on keeping him. Matisse’s biographer Hilary Spurling tells us Pierre was angry with his father about this, but I wonder how Teeny felt. Was she upset to have her dog taken from her by the demanding artist, did she take it in stride, or—as I like to imagine—was she happy to please her beloved father-in-law?

The clip was sent to the Barnes and the museum in Paris, and it appears in the 2014 Exhibitions on Screen documentary about Matisse’s cut-outs and probably isn’t hard to find elsewhere at this point. But I doubt anyone in the art world knows the film came to light because of a séance.

AGNES MITCHELL SATTLER (MOTHER OF AGNES AND TEENY), ARCHIVAL FOOTAGE OF

HENRI MATISSE AND “THE DANCE,” NICE, FRANCE, APRIL 1932 © ARCHIVES HENRI MATISSE

In the middle of November, I got a call from my mother’s accountant, who explained that, since we had no idea what Donald Trump was going to do with tax laws regarding “noncash charitable contributions,” I might want to be on the safe side and try to wrap everything up by the end of the year and make the Boîte a 2016 gift. This presented a bit of a dilemma. For me, insuring the Boîte’s survival as an unusual relic of modern art, combined with its sentimental value to our family, outweighed the issue of its monetary worth. At the same time, I knew my mother wouldn’t be happy about the possibility of losing the tax deduction, and I didn’t need a séance to feel the spirit of my businessman father exerting some influence from beyond the grave.

Up to that point, we hadn’t been in any hurry. I had been proceeding methodically for almost five months, consulting the experts at each stage before moving forward. But Scott Gerson had already told me he’d probably have the conservation work done by the end of the month, and he was still on track. Once that was completed, Jonathan Rendell of Christie’s could go to Scott’s studio to appraise the fully restored Boîte. There would be forms to fill out and legal documents to complete, and the Boîte would have to be in the museum’s possession by December 31—assuming they wanted it, which was still not clear.

The following week, however, Cameron Kitchin wrote me saying the Boîte from the other collector was a Series F, the edition after ours, and he assured me ours was still “highly relevant and of value to the Cincinnati Art Museum.” Despite that slightly stilted phrasing, this was good news.

When Scott finished his work, Jonathan Rendell was in London, so the appraisal had to wait a week for his return. During that time, my mother, my brother, my sister, and I discussed the phrasing of the credit line for the Boîte, which needed to be part of the Deed of Gift and would appear on the museum label whenever the Boîte was displayed, and in the citation whenever it was reproduced in a publication. We liked the idea of honoring the Sattler sisters, Agnes and Teeny, since they represented this artwork’s main link to Cincinnati, one of them having owned it while the other had been married to its creator. We also wanted the gift to be not only from our mother but from the whole family. The slightly cumbersome final credit line reads: Gift of Anne W. Harrison and family, in memory of Agnes Sattler Harrison and Alexina “Teeny” Sattler Duchamp.

JACQUELINE MATISSE MONNIER, TEENY AT THE GRAVE OF JAMES JOYCE, ZURICH, 1991

I often thought of Teeny and Aggie during this project. Though I never attended a séance to make contact with them, I did have a dream in which I found a letter Teeny had written to Marcel after his death, but I couldn’t remember what it said when I woke up. Then I dug up Teeny’s actual letters in the attic, and was amazed to be reminded how much traveling she did well into her eighties—often to see exhibitions of Duchamp’s work or to watch chess tournaments in European cities. She died in December 1995, almost ten years after my grandmother, just shy of her ninetieth birthday. In one of our photo albums there’s a snapshot, taken by Jackie, that feels like a farewell: Teeny is standing at James Joyce’s grave in Zurich, looking dapper in a khaki-colored summer suit and black dressage hat, like a flat-topped bowler, with her back to the camera and her cane held at a jaunty angle.

I drove down to New York for the meeting at Scott Gerson’s studio in early December, because I wanted to see the restored Boîte before it left the family and to hear in person what Jonathan Rendell had to say about it. My son and daughter, William and Eliza, both living in Brooklyn, came with me. Scott went through the Boîte item by item, pointing out some of the repairs he had made. The green imitation leather covering on the outside of the Box looked glossy and new, and the black paper that held some of the reproductions had been cleaned and now had a velvety richness. Jonathan said the Boîte was in better shape than most of the ones he’d seen, both because we hadn’t handled it much and because of Scott’s restoration. He and Scott were both surprised that the celluloid of The Large Glass replica hadn’t broken down at all, the way it had in other examples they’d seen. Consulting a yellow legal pad filled with notes, and citing the recent “hammer price” of another Series E Boîte, Jonathan gave ours a valuation in the low six figures, and beyond what I had anticipated.

With our business done, everybody loosened up. In reference to Eliza’s internship, Scott called MoMA “the velvet coffin,” saying he was glad he had managed a Houdini-like escape. Jonathan shared amusing stories about auctioning Yves St. Laurent’s collection and Elizabeth Taylor’s jewelry. I recounted the checkered history of the family’s Calder mobile, saying it was probably worthless because of the damage from the BB guns and the repainting. “Oh, no,” Jonathan said with a smile, “everything has a price. And anything can be restored.”

Only after Jonathan left and the banter had subsided did I become aware that my high spirits at the Boîte’s successful restoration and generous appraisal were underscored by a bass note of sadness. I had been too distracted to fully take in the moment. Now, as William, Eliza, and I gathered our things and put our jackets on, and Scott began returning the various items to their places inside the Boîte, I realized it wasn’t just the three of us leaving his studio: the Boîte was leaving the family, being sent off, for better or worse, to its own velvet coffin.

A surprising number of documents needed to be signed and countersigned over the next few weeks. In my mother’s letter officially donating the Boîte to the museum, she wrote, “Although Teeny’s life was more cosmopolitan than that of her sister Agnes, she was always very down to earth. She was a truly amazing person. She had glamour, charisma, and charm, and she was also very kind. She was always interested and engaged with whoever she was talking to.”

Scott Gerson dismantled the main sections of the Boîte and packed them separately to avoid damage, then arranged for the crate to be shipped to the museum. After some delay, the Boîte finally arrived at the museum on December 29, two days before the deadline. The registrar waited twenty-four hours to unpack it, allowing it to acclimatize to the museum’s environment, as though the Boîte were a living creature needing rest and rehydration to recover from its journey back to Cincinnati.

Julie and I celebrated by going to Paul Matisse’s New Year’s Eve party at the church. Round tables with white tablecloths and floral centerpieces surrounded the large space that had once held pews, and a jazz band played on a small stage where the altar had been. The middle of the room was left open so that everyone could dance under Paul’s hanging sculpture Ulysses, a glimmering arrangement of hundreds of metal rings containing small lights suspended at varying heights. At midnight, white paper hearts fluttered down from a secret chamber in the ceiling.

While I was still working on this essay, Jackie died after a long illness. She had been living in her mother’s old house in Villiers since Teeny’s death in 1995. Paul recently turned ninety. At a lunch we had together last year, he read me a list of all the things he still wanted to do. It was a long list—including one of his bell projects and making a kalliroscope for each of his children (and one for me, he said). I hope all the tasks he wants to complete will keep him going for years to come. Nevertheless, I have the sense that something dear to me is slowly fading, like the sound of one of his bells.

In early 2018, the Cincinnati Art Museum had a small Duchamp show centered around the Boîte. My mother and I were invited to the opening reception and to a lunch at the museum the day before, February 14. Without even checking with anyone at the museum, I wrote Anne Goodyear asking if there was any chance she could join us, remembering that she had a sister living in Cincinnati. She enthusiastically accepted, attaching to her email an image of the original version of Fluttering Hearts, from 1936, and pointing out that Valentine’s Day, the day of the lunch, was the perfect time to celebrate our gift to the museum.

Anne arrived at the museum’s restaurant with two red Valentine’s bags full of goodies for my mother and me. After lunch, she joined us for an interview with a reporter from the local arts and culture newspaper. I summarized the family’s history with the Boîte, while my mother inserted humorous asides about how she’d kept the Boîte under my brother’s bed for decades, or how Pierre Matisse must have been an idiot to leave a wonderful person like Teeny. It was no surprise that Anne Goodyear was more articulate than either of us on the subject of Duchamp. “Although we think of Duchamp as an extremely cerebral person,” she said, “something I’ve come to appreciate about him a great deal is that … he had a very strong affinity for family. This particular object provides so much important information about Duchamp, his family, and even the role of Cincinnati in how it shaped Teeny and her sister Agnes.” She added, in a bit of a stretch, “It is obvious that this Box was being well cared-for in the context in which it lived,” but it felt right that it had made “its way from this family into the public arena.”

After the interview, we finally went to see the Boîte, which was displayed in the center of a small gallery, its various elements spread out on a wide stand. There were other Duchamp-related works on the surrounding walls, including an intaglio print of his Coffee Mill and a portrait entitled M.D. that Jasper Johns had created by cutting a slit that traced Duchamp’s profile into a sheet of heavy, cream-colored paper. But the Boîte dominated the room. Fluttering Hearts was prominently featured, with Duchamp’s inscription on the label, and under the museum’s spotlights the alternating red and blue of the outsized heart seemed to throb with life.

AGNES HARRISON, RUFFMUNG FARM HOUSE

I thought about the long journey the Boîte had taken, of all the rooms and spaces it had spent time in, beginning with the chambre de bonne in Paris where Jackie had assembled it, and where Julie and I had later stayed, not yet aware of the connection. Then, in my grandparents’ yellow farmhouse in the countryside outside of Cincinnati, now long gone, the Boîte had been surrounded by other art: the drawing of Teeny by Matisse, the Calder mobile, the otherworldly stone mask from Teotihuacan that they’d bought from Pierre Matisse, and all of my grandmother’s paintings. Later, the Boîte spent its Rip Van Winkle-like hibernation under my brother’s old bed in the big brick house where we’d grown up, followed by its brief oblivion in the attic. Next, it took a summer vacation to a cabin in the Adirondacks, had a short layover in my own house outside of Boston, and underwent a rejuvenation in Scott Gerson’s studio in New York. A box full of miniature artworks, the Boîte had spent most of its life as an artwork among other works of art, in spaces that were themselves like larger versions of the Boîte, some of whose chambers can be opened and panels pulled out only in memory. Now it had returned to Cincinnati, its former home, to join another space, taking its place among thousands of other works on public display. It was literally on a pedestal, and it felt like an honor—not for us, but for the Boîte itself and, because of our dedication, for Aggie and Teeny.

As we left the room, I looked back to see two museum preparators lift a large, aquarium-like, plexiglass vitrine that had been removed for our visit and lower it onto the broad stand, encasing the Boîte so that it now felt out of time, like an ancient kit of ritualistic objects and totemic images.

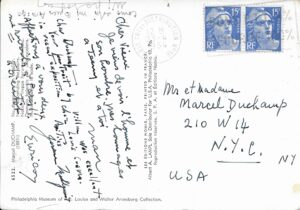

POSTCARD OF NUDE DESCENDING A STAIRCASE, FRONT AND BACK

During that same trip to Cincinnati, my sister asked me to go through some boxes of my stuff that were still in what was now her attic and either take them or get rid of them. One of the cardboard boxes, labeled CANTALOUPES, was full of old art books our grandmother Aggie had owned. I vaguely remembered packing them up in the early eighties when she moved from her house to a retirement community, then stashing the box in my parents’ attic to be dealt with (like the Boîte) later. Now, going through the books after more than thirty years, I came to a catalogue of a show of etchings by Jacques Villon, Duchamp’s brother. When I opened the book, a postcard slipped out and fluttered down, landing faceup on the attic floor’s rough boards: Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase. Postmarked April 23, 1954, from Paris, the card was addressed to “Mr. et Madame Marcel Duchamp” in New York, and bore handwritten messages from four people in three languages: English, French, and Spanish. One note was clearly signed “Man,” and my heart quickened as I realized it had to be Man Ray. The other signatures were harder to make out. On the front, in the white margin next to the image of his painting, Duchamp had inscribed the card to my grandmother: “Pour Agnes toute affection Marcel.”

Later I deciphered another of the signatures as “Wifredo,” and surmised it was the Cuban artist Wifredo Lam. I scanned both sides of the postcard on a printer at my mother’s house, where I was staying, and emailed the images to my cousin Antoine and my friend Charlie Brock. In no time Charlie recognized the signature of Jerome Mellquist, an American art critic of that era, and Antoine identified Enrico Donati, the Italian American surrealist. Clues in the messages indicated the four of them had gone to a Jacques Villon show together before writing the card.

By signing the card himself, Duchamp had shown that he knew it was more than an ordinary postcard. And like the postcard of the Mona Lisa he had adorned with a mustache and goatee, he had turned this one into “a Duchamp.” Finding this artifact transformed by time and the hand of an artist felt like a sign, a gift sent by the guardian angels of art, by the sister spirits of Agnes and Teeny, or by Duchamp himself.

Jeffrey Harrison is the author of six books of poetry, most recently Between Lakes. His poems have appeared in Best American Poetry, the Pushcart Prize volumes, and many magazines, including The Common.

Footnotes

1 Some of the biographical facts in this essay come from Duchamp: A Biography, by Calvin Tomkins.

2 It should be noted that Paul broke this pattern by encouraging his children to become makers.

3 The details about Albert Barnes—and, below, about the dog—come from Hilary Spurling’s Matisse the Master: A Life of Henri Matisse.