JENNIFER ACKER and CURTIS BAUER interview ROSS GAY

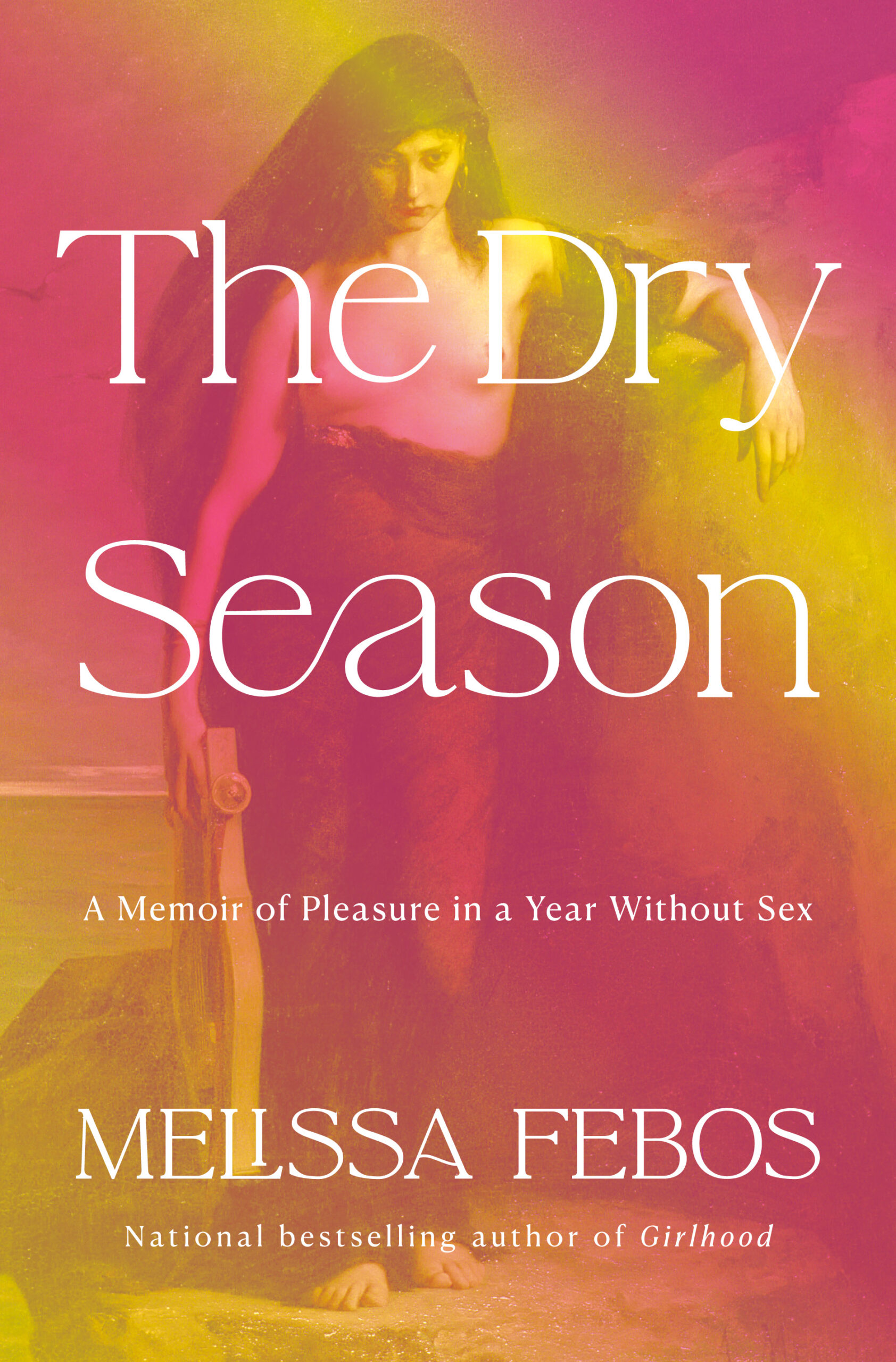

Ross Gay is the author of the poetry collections Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude, winner of the Kingsley Tufts Award and a finalist for the National Book Award and the National Books Critics Circle Award, Bringing the Shovel Down, and Against Which. In February he published his first book of prose, The Book of Delights. At the 2019 AWP Conference in Portland, OR, The Common’s editor in chief, Jennifer Acker, and Translations Editor, Curtis Bauer, sat down with Ross over lunch to talk about his latest book, which has led him to realize his life’s work.

JA: It seems to me that your two recent books, the Catalog of Unabashed Gratitude and The Book of Delights, were written in a similar vein and in a similar spirit, even just from the titles. One of the things they’re both doing is thematically trying to draw attention to joy and delight. I wonder if they were consciously part of the same project, different outlets for a similar impulse?

RG: I’m not positive about this, but I do feel with the Catalog book, that after hearing people react to it, I had the opportunity to theorize and think hard about things like joy in a different way than even when I wrote that book. The way that people have responded to that book was not at all expected; I didn’t realize that people would say things like, “It’s so joyful.” I didn’t actually expect that, so I’m glad, I’m really glad.

JA: That wasn’t a conscious part of the writing process, or it was and you just didn’t know if it was going to be noticed?

RG: I was just writing these poems, you know, and then it occurred to me. I think just the fact that there’s celebration in the poems makes people feel a certain way. But I also feel sometimes there’s a misreading or an under-reading, that neglects to pay attention to the fact that the little girl at the end of the title poem says, “The world is about to end.” That’s what she says (chuckles). And the speaker, who is me, says, “I know. I know. That’s why we’re doing this.” So when people are like “Optimism!” I’m like, “Labor!” Like work, gathering.

JA: Do you think that says something about what people are reading for, or what they want out of poems these days?

RG: I think maybe it does suggest something about a kind of bleakness. I think our inquiries most often are about what’s difficult—because we’re really confused by it, as am I. You know, happy shit is awesome, but it’s not particularly interesting to me.

JA: One of the Delights starts out by talking about the winter equinox, and that’s paired with a pretty purple scarf, but those two things are consciously juxtaposed. It made me wonder whether in writing these delights if you think that part of something being a delight is its necessary proximity to darkness or despair.

RG: To me, yeah, absolutely. I’m glad you thought of that one in particular. In thinking of this infinity scarf that my former student and friend Dani made, one of the things I’m thinking about is that the winter equinox is the shortest day of the year in certain parts of the world, especially the Philadelphia area where I’m from. It’s getting to be cold, and that’s the shortest day, and after that the days get longer. And it actually matters. Just because we’re just so absolutely uninvolved in the natural processes of the world does not mean it doesn’t matter. That equinox, and the celebrations of that and all celebrations of earth things, is one of the ways we acknowledge that the earth does not need to provide us anything. And the equinox is this moment: Come back light, you know, come back light. (chuckles) And to me, that’s the first gratitude, that’s the original gratitude, that the earth provides us with anything.

JA: It makes me think about New England seasons, that we appreciate spring so much because we’ve just had winter. (laughs)

JA: It makes me think about New England seasons, that we appreciate spring so much because we’ve just had winter. (laughs)

RG: (laughs) Yeah totally.

JA: If we lived all our lives in southern California, maybe we’d feel differently.

RG: We’d have other systems, like the rains. We’d ritualize the rains, or the end of the rains.

JA: It sounds like darkness and light bumping up against each other was a conscious part of making these poems, but perhaps grew even more conscious in The Book of Delight. Is that fair to say?

RG: I think that it became more intentionally an inquiry because I was able to think about this with other people. This has led me to realize, Oh that’s my work. My work is to think about, study, point to joy. Joy is made of our death and pain and sorrow etc., just as it’s made out of our ability to be with each other and have food, that kind of stuff. So it kind of helped me find out what I want to do with my life.

JA: Wow that’s a really big thing.

CB: It is a huge thing. Do you think this will change how you’re going to go back to writing poems? And is there anything else you’ve learned from writing this book?

RG: This book was more or less written every day. I think I got to the upper two hundreds, maybe three hundred attempts, but nearly every day. That’s something I don’t know that I’ll do again unless I do it as a job. The practice of attending very closely to something that mystified me, that I wanted to think about in a quick, though thorough, way—I definitely think that was a practice that is now informing my other work. I’m now writing a book about the land, a nonfiction book that’s sort of a longer essay. There are these moments in there that feel like delights. There are these little reveries that are asides or parentheticals, and I feel very much like I learned this form through writing these essays.

JA: In the preface to The Book of Delights, you talk about forming a delight muscle, right? Training yourself to look at delight, and how that’s sort of blossomed into a larger purpose. But since you’ve just been talking about the things that go along with delight, the pairing of emotions, did it make you more perceptive to sorrow and pain, a general heightened perception?

RG: It maybe did. I think that sometimes I can neglect to attend to the things I love and adore and want to celebrate, want to preserve and share. I think the practice of writing these delights definitely gave me the opportunity to bring those things into focus. To be able to more precisely articulate, “Oh these are the things that I want to preserve: like public space, or common space, or the ways that people can be kind to each other.” These are the things that I want to exalt. I suspect that in realizing what the things are that I do want to exalt, that the whole time I was also realizing part of why I wanted to exalt them is because I’m aware of their absence. That’s part of the “theorizing”—I put that in quotation marks—I’m doing in the book: Why does that delight me, why is there a deficit of that in my life, or in anyone’s life?

JA: One of the beautiful progressions of the book for me was that it seemed like as we got to the middle there were several little “essayettes,” as you call them, in a row that were speaking particularly to human connectedness. There’s an essay about the train in which you talk about the everyday caretaking, or the ongoing caretaking that people are doing for each other in just little things like holding open doors.

RG: I mean the woman [the bus driver] on the bus today [turns to Curtis]—we messed up, we did it wrong—and she was like, “Just stay on and we’ll circle around.” And she was like making eyes with us in the mirror…And before that we were sitting in the seats that are reserved for handicapped and the elderly. This older woman with a basket got on the bus. I got up to give her a seat, and she touched my arm and said, “No, no, no.” I think she was speaking another language, but she must have been saying “Stay.” She didn’t want us to move, she wanted us to stay with her. (laughs) You know? It’s that kind of daily shit.

CB: I think something for me with these [delights] and with Catalog is that there’s a lot of touch, there’s a lot of human contact. And I think we have a deficit of human contact because of the electronic; we’re somewhere else instead of being in the present right now, right? Drawing attention to this allows us to think about the deficit of touch in our own lives.

RG: And too, this celebration of touch is also an acknowledgement of violence, violent touch. One of the Delights that happens three or four days before the [2016] election is talking about this guy who was a flight attendant. I don’t usually have the experience of flight attendants touching me, but he was another black dude. And he was like, “Hey.” And the feeling of that was feeling beheld. Structurally, historically, we have been touched in other ways, you know. So there is this thing of wanting to attend in some way to both [violent and tender touches], and to be like, the tenderness is the thing that I want to study. I want to know how do that and be with that.

CB: So today we were talking about the gaze, looking at someone, looking at the eyes, holding that, not being afraid. So it kind of goes both ways. As a flight attendant or as a teacher, maybe I’m not supposed to touch you, but there’s a certain need at a certain moment in which you’re aware of that body, and of that person’s need to receive it.

RG: Yeah, yeah, yeah. Yeah.

JA: As I was thinking of this delight muscle, I was thinking about this analogy about taking photographs of something you think is beautiful. One of the things that happens if you’re taking photos all the time is that it takes you out of the moment. Is there any way that noticing, not just noticing but turning the noticing into work, into essays, is it kind of a bummer, or did it take you out of the delight, take the fun out?

RG: Not at all. Nowadays looking at a picture also entails like, being aware of Boop!, here’s this new story. Boop!, here’s this new other thing. But the writing was a kind of meditation, a contemplation. I had this moment, it was amazing, when I was thinking about all the stuff that I had done for the day, like the work on my little checklist. And I was like, oh I did this administrative thing, I got this paperwork in, that person will graduate, blah blah blah. And I was like well, there’s an hour and a half that I can’t account for. What was I doing? And then I was like Oh, I was delighting! I was thinking about delight. And it did not coincide with my idea of labor, of work. My experience was that I could not register delight and work as the same thing. I want my labor to be delightful.

CB: We think about the life of the contemporary poet or the contemporary writer, and how we’re in the academy, and that’s how we’re paying our mortgage or whatever. But the real delight, what keeps us going, is writing that work, right?

RG: Uh-huh.

CB: But it’s connected somehow to our job.

RG: Yeah, but we’ve been talking too about how teaching is delightful. I think the best teaching comes from wonder, a kind of mutual wonder. And the best writing, at least for me, what feels the most interesting and the most fulfilling, is writing that comes out of wonder. Like I’m curious about something, I want to approach it, but I don’t know how. And I’m gonna do it in a community too, in the community of writers who are in my body and in the community of folks I share work with. Which is what a classroom space is, which is work. (laughs) But once it stops being I gotta do this grading, and you’re with people thinking about shit you don’t understand, it’s actually kind of like the same thing. It’s like writing a poem.

I just had this class that Curtis knows about. In the fall I taught this class that felt like one of the most wonderful classes I’ve taught. I’m figuring things out, I’m learning how to teach a little bit better. And there was just a lot of people being in a room together thinking hard, in care, fully engaging with mystery and supporting each other in doing that. And writing a poem is sort of like that. Anyway, that’s just my way of arguing that the work of being with people that we call teaching is just like the work of engaging with the mystery.

JA: Curtis, fight back! (all laugh)

CB: Yeah, but has that changed because of the attention to the delights?

RG: Yeah, because what I think of as the political vision of the book, the ethical vision, is this process of articulating and discovering how best we can de-alienate ourselves from one another. And that also is what my teaching life hopes to be: how do you make a space that supports everyone, allows everyone to be themselves as much as possible, in a sort of joyful way that also can hold what is painful and difficult and brutal often. That’s the space that I’m trying to make or be with. That’s the space that I value. Is that clear enough?

JA: Yeah, you’re creating that space on the page and in the classroom. And you can use a similar approach to both.

RG: The thing that I think I’m trying to really attend to are these little moments of care and sharing and togetherness and collaboration. Universities mostly do not—aside from the little internal grants that say “If you collaborate…”—value that stuff. They value the same shit as every other world-destroying thing. And so to teach a class that tries to envision this other thing, which is sharing, collaboration, caring for each other, honoring each other’s bodies by bringing food to the classroom, or being like, “Let’s rest now,” or being like, “You all have written really hard for the last three weeks, and maybe now we shouldn’t do so much. We should just talk tomorrow, or just potluck.” That’s a good thing.

CB: You corrected yourself; you said political and then you said ethical.

RG: It’s totally political.

CB: How making these choices, how you’re going to approach teaching a class, not following particular rules like, “This is how the workshop needs to look like” or “You need to have a syllabus for this.” Or loitering. I have a friend who likes to call it “practicing laziness.” To be outside of the system…

RG: Yeah.

CB: That is a real political view and stance.

RG: If a tenth of us were like, “We’re going to share all our shit.” That’s very disruptive, you know. I think it disturbs conventional notions, which are mostly myths anyway, ideas of ownership and property and what is possessed, and what can you possess, and what violence is it to possess? On and on and on, you know, and I do not think we’re taught that in college or university. (laughs) And the grading, the evaluation itself, it feels like a direct connection to so many of the violences, just another iteration of the violences that we could totally hang out over and enumerate.

CB: I’m thinking of the word “rigor,” how often programs are talked about as a “rigorous” program of study. To turn that upon its head and say, “we’re gonna practice rigorous laziness.”

RG: Yeah.

CB: Or be rigorous in how we’re kind to each other, how we care for each other.

RG: Yeah, totally. Those words, like the word “discipline.” “Disciple” means one that follows, so I like the idea of following something, like a calling. I played football in college, and I’ve been a coach. So part of my discipline relationship is a punitive, violent notion of how to get shit done. So I like the idea of practice more, because even the word “rigor,” like when you said it, I was like, “Oh that’s rigor mortis.”

CB:. We’ve shared some teachers. I’m wondering who you were looking at for guides when you wrote this, when you approached the craft of the delight. There are some obvious mentors or teachers who appear in your poetry, but do they carry over to your prose?

RG: Well, Tom Lux, who was our teacher, died about halfway through [my writing the delights]. There was a delight about Tom but I couldn’t figure out how to write it. But he has a spirit about him. He has that one quote, “On one hand the rapture and on the other the rage,” something like that, I think it’s a prayer for his daughter [“For My Daughter When She Can Read”]. He is someone whose spirit I see in that. Gerald Stern for sure. Toi Derracotte. She’s a writer who I just adore. She can hold so many things at once. There were a lot of people I was reading when I was writing these things. Rivka Galchen has this little book [Little Labors], it’s physically just such a beautiful little book. Renee Gladman’s book [Calamities]. Maggie Nelson’s Bluets. Brian Blanchfield’s book [Proxies]. Blanchfield has this relationship to knowledge, which is basically that he doesn’t check anything while he’s writing these essays, he just says stuff. And then at the end, there’s this beautiful essay called “Corrections,” I think, where he fixes everything that he got wrong. (laughs) And I was like, that’s the best. So I was starting to do it, but I wasn’t doing it very well, and my editor was like, “So why wouldn’t you just Google that?” (laughs) And I was like, “Good point.” I did not pull that off like him. So it’s just that spirit of that way of thinking that was so in the book. This writer Sara Ruhl who’s a playwright mostly, she has these essays that were really, really important to me. Margo Jefferson’s work, all of these essayists that I was reading like crazy, and who I feel like I can see their work in here.

JA: And your revision process? You said you wrote about two hundred delights, or you’re writing them over the course of the year, so you had maybe not quite three hundred and sixty five of them, but then what was the winnowing and revision process?

RG: I wrote them all by hand, so I had these notebooks and periodically I would transcribe them into the computer, not changing them at all. If they were terrible I wouldn’t transcribe them. I’d just leave them out. There were a lot like that. Then I would read them out loud, and that was the first real revision process. Hear what they sounded like and hear how people heard them and then go back in and work on them. Probably by the end I typed up two hundred and some. I lost a notebook too, one of the best ones in the book, I left it in the airplane. (laughs) It was really so good!

CB: It’s gonna come out, The Lost Delights.

RG: I actually wrote the airline and was like, “Hey.” They did not give a shit. So we finally got it down to around one hundred and forty, one hundred and forty-one. I have a great editor, Amy Gash at Algonqin, she’s really wonderful, she’s just sort of saying, “Oh, you’re repeating yourself,” or “There’s an awful lot of babies, Ross.” I was like, “Alright, I’ll take a couple babies out.” (laughs)

JA: There aren’t that many babies in the book. I guess you took them all out. (laughs) A lot of redbuds.

RG: A lot of redbuds! Yeah, that’s another thing she said. I probably cut out two redbud ones. (all laugh) It was either redbuds or, you know, hugging.

JA: Another thing that comes up in the Delights and then I saw you mention this in an interview as well, and I thought “Wow he really must think this all the time,” which is just looking at bodies, and the fascination of bodies, and how they move. That observation is often in proximity to the thought, “Someday, that body is going to be dead.”

RG: Yeah. I was just thinking that on the bus.

JA: See? You do think it all the time. (laughs)

RG: Yeah, I was sort of thinking, what will it be like when we’re all gone? On the bus there was something that made me think that.

JA: As in all society or those sitting on the bus right now?

RG: No, I was thinking about all of us.

JA: The end of the world.

RG: Yeah.

CB: But you were looking out the window…

RG: No, I was looking at us.

Curtis Bauer is the author of three poetry collections, most recently American Selfie (Barrow Street Press, 2019). He is also a translator of poetry and prose from the Spanish; his publications include the full-length poetry collections Image of Absence, by Jeannette L. Clariond (forthcoming from The Word Works Press, 2018), Eros Is More, by Juan Antonio González Iglesias (Alice James Books, 2014) and From Behind What Landscape, by Luis Muñoz (Vaso Roto Editions, 2015). He is the publisher and editor of Q Avenue Press Chapbooks and the Translations Editor for Waxwing Journal. He is the Director of Creative Writing Program and teaches Comparative Literature at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas.

Jennifer Acker is founder and editor in chief of The Common. Her short stories, essays, translations, and reviews have appeared in the Washington Post, Literary Hub , n+1, Guernica, The Yale Review, and Ploughshares, among other places. Acker has an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars and teaches writing and editing at Amherst College, where she directs the Literary Publishing Internship and organizes LitFest. She lives in western Massachusetts with her husband. The Limits of the World is her debut novel.