Driving on the Peak to Peak Highway through Colorado’s Rockies with my husband, Bill, and his mountain-climbing friend, Bob, I glimpsed in the valley beyond a cluster of low buildings painted blue, pink, and green. It looked as if a 19th century frontier mining town had been transformed by a happy band of pot-smoking hippies who had journeyed cross-country from Woodstock. The incongruity was so pronounced, I wondered if the air at 8200 feet had thinned my brain cells, causing hallucinations.

“What is THAT,” I blurted to Bob and his wife, Jean, who’ve lived in Colorado for decades. With a strange laugh, he answered, “Nederland.” That brought Neverland to mind, a name that seemed to suit the place perfectly—maybe Peter Pan and the Lost Boys lived there? Bob agreed to stop in the town after our hike.

And so we did, drawn first to the timbered Town Hall. A post outside provided some historical context: Nederland was the name of a Dutch company that owned the nearby Caribou Silver Mine. When the town was incorporated in 1874, it was still serving as a supply center and mill for the booming silver industry. I found it hard to imagine 3,000 residents (double the current population) bustling about these almost preternaturally quiet streets. When the mine closed, Nederland became just another ghost town—that is, until tungsten was discovered, turning the unlikely little hamlet into the world’s largest producer by World War I.

I was disappointed that we had only an hour for Nederland if we were to make our Saturday-night dinner reservation in Boulder. A rushed visit seemed contrary to the spirit of the town, where ZZ Top look-alikes sporting long gray hair and beards and younger, neater versions of themselves ambled along. I consoled myself that this would be an “amuse bouche” taste of the quirky place.

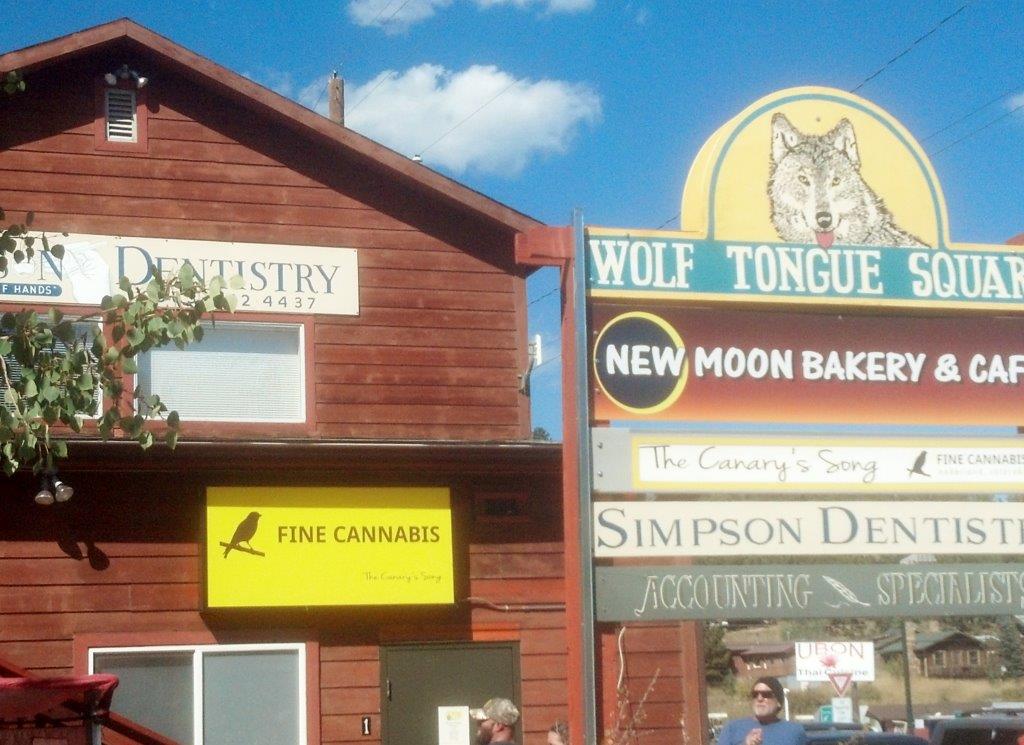

Bob and Jean settled down to wait for us at an outdoor table of the New Moon Café, known for its Chai Organic Latte and gluten-free baked goodies. Bill and I gulped down an espresso before dashing off like some kind of Lewis and Clark duo on speed.

The first stop was right next door: The Canary’s Song Marijuana Dispensary. Bill was reluctant to cross the threshold, but I egged him on, saying, “Think of this as a kind of sociological field trip,” which did the trick. We knew that pot was legal throughout the state, but it wasn’t until we returned home that I learned Nederland had been dubbed “Stonerville U.S.A.” by Rolling Stone. Pot tourism, including America’s first legal cannabis café, brings lots of visitors—and tax income—to the town.

The pungent aroma of unsmoked cannabis filled the reception room, where a pleasant young woman greeted us. After showing our IDs, she opened the door behind her table to the inner sanctum. With its low lighting and hush, the room felt like a church. A slim young guy with a neat beard stood at the glass-topped altar at the far end. “Just browsing,” I wanted to say as I would to a department store clerk, but there was no need to explain our intentions. This mellow fellow was the opposite of an aggressive salesman—in fact, I later read that he’s called a “budtender,” a much-desired job in Colorado.

To educate us, he reached below and placed three locally grown green-gold clumps of marijuana on the glass, naming each one (Jack Flash, Blue Dream, etc.), commenting on their scents as a wine connoisseur might describe a buttery aftertaste or peach undertone. A wall poster listed the percentage of TCP in each product, while another described the benefits of grass for various ailments. The budtender also pointed out Canary’s variety of edibles and “topicals”—gels, massage oils, and lotions. I wondered aloud about the separate medical counter, where marijuana samples lay inside old-fashioned apothecary cases, but was told that area was reserved for people with prescriptions.

Between the powerful smell of pot and séance-like lights, it all felt surreal and brought me back to another, distant time in my life. New York, my state, hasn’t approved medical marijuana, but here we were in a pot store two doors down from Town Hall. According to a brochure, customers could even get discounts through a “Silver Seeds” reward program.

“Enjoy the cooler weather that’s coming,” Bill said as we were leaving. (It was mid-September, and the mountains were dotted with russet patches.) “August is almost here,” the budtender replied, smiling beatifically. Back in the sun, we laughed. But having worked at so many high-pressure, deadline-driven jobs, I half-envied this guy, oblivious to time. Like Las Vegas, there were no clocks in the Colorado Church of Cannabis.

Outside, with the Rockies as backdrop, I felt I was in a cowboy movie. The arid streets were sun-struck, and tumbleweed danced along. Next stop: the pink-and-turquoise Natures Own store, packed with minerals, crystals, fossils, and jewelry by local artisans. I scanned a revolving rack and chose a purple “geode slice” magnet to remind me of Nederland’s early history. In what felt, and was, a whirlwind tour, we took in the Pioneer Inn with its intact hitching post, an artists’ collective gallery, a food co-op where swallows nested on the front porch, an alpaca store, shops stocked with sports equipment for the great outdoors, and several independent bookstores. I noticed that many businesses provided much-used outdoor community bulletin boards—just one detail leading me to conclude that today’s Nederland could have been cute and precious but has instead retained a proud-to-be-rough-around-the edges feeling.

Rejoining Bob and Jean at the café, we wondered how different the vibe might be in winter. The season attracts skiers and snowboarders, they told us—but the bigger crowds converge on Nederland for its Frozen Dead Guy Days Festival every March. The Frozen Dead Guy is a Norwegian known as Grandpa Bredo, who died in 1989. A true believer in cryonics, he was shipped in dry ice to a cryonics facility in California, and then to Nederland, home of his daughter and grandson. They’ve kept him on ice in a shed above the town, assisted since 1995 by a paid “Ice Man” and team of volunteers who haul the 1600 pounds of ice needed every month to prevent Grandpa from thawing prematurely. The Nederland City Council could have ended this but chose instead to change the city code on “the keeping of bodies” to accommodate the unique circumstances.

So everyone is happy: Grandpa Bredo’s relatives; the town, which reaps the economic benefits of the tourist influx; and the visitors, who get to watch coffin races and participate in “Snowy Human Football,” costumed polar plunges, “brain freeze contests,” and other bizarre entertainments.

Checking my watch, I saw that we had to move on. But I’m glad I spent even one hour in this eccentric town. In a way, Nederland is the quintessential American success story, experiencing several booms—gold, silver, tungsten, and now marijuana—and some major busts, but managing a comeback every time.

Maria Terrone is the author of four books of poetry. Her work has appeared in such magazines as Poetry, Ploughshares, The Hudson Review, and Poetry International, and more than 25 anthologies.

Photos by author