Curated by SAM SPRATFORD

The summer months, with their sprawling days, coax us to explore new literary worlds. If you’re not reading Issue 29—which features short stories from Hawai‘i, Kenya, Baton Rouge, and an Austin boxing gym—these recommendations from its contributors TERESE SVOBODA, NICOLE COOLEY, and BILL COTTER will help to revive the childhood magic of summer reading. Read on to discover poetry and prose titles that give permission, immortalize, and remind us how “fiercely beautiful” words can be.

|

Molly Giles’ Lifespan and Alexis Wright’s The Swan Book; recommended by Issue 29 contributor Terese Svoboda

Molly Giles’ 2024 memoir, Lifespan or the novel The Swan Book published in 2013 by Alexis Wright? The first is a perfectly wrought, very moving series of flash pieces of a life experienced above, under, around, and on the Golden Gate Bridge. The second is a wildly inventive, messy novel about the love of Australian black swans by a rebellious woman abducted from a swamp to be the wife of the Australian president. I won’t choose.

Giles’ witty and witless voice in Lifespan celebrates each of its brief but gripping narrative sections, from ludicrous encounters with wicked hyper-articulate parents, to equally challenging teenage children, to bad matrimonial choices. She faces alcoholism and we don’t blame her; she’s without a shred of emotional support. Unsentimental in the extreme, the book is a delight. Don’t do it! the reader admonishes, fully aware her own biography would never stand up to such pitiless scrutiny. Examined as daughter, wife, mother, and grandmother through the abiding lens of a determined writer, writing is the one constant. She’s so articulate about the demonic urge to write—“I just want to be able to say what I don’t yet know how to say in a way that says it so well even I understand it”—and fully cognizant that writing is what electrifies a memoir, not the events of a life. “I like the way his big hands look on the steering wheel and I like the way he sings to himself underneath the chatter of the radio,” she describes her father when she’s three, before later painful revelations set in: “The parents in my novel were cruel to their children, two-faced to their friends, casually hateful to each other. They were the parents I knew.” The Golden Gate Bridge links everything, even the consoling late relationship setting sail into the sunset below the bridge. Most memoirs are: Read it and sleep. This one will keep you up.

Alexis Wright’s third novel, The Swan Book, is a brutish dystopian fantasy set in the midst of a worldwide climate crisis. An eccentric European exile from the Climate Wars finds Oblivia hiding in the trunk of a eucalyptus after a gang rape which leaves her mute. Oblivia befriends a huge flock of black swans attracted to their shrinking Northern Australian lake, but is abducted by an ambitious indigenous politician. “He was the lost key. He was post-racial. Possibly even post-Indigenous. His sophistication had been far-flung and heaven sent. Internationally Warren. Post-tyranny politics kind of man.” Aunty Bella Donna of the Champions, the Harbour Master, Big Red and the Mechanic, a talking monkey called Rigoletto, and three genies with doctorates who, as bodyguards, come to a bad end, people her narrative. She gets everything almost any Australian girl would ever want: a handsome fairytale prince, wealth, a much-vaunted position in society— but it’s not hers. Oblivia has “a virus lover living in her brain,” meaning her indigenous culture that evokes enormous sensitivity to the ongoing destruction wrought by other cultures. Destroying a climate and destroying a people have parallels. The book reflects the Australian government’s 2007 Intervention, which disastrously changed welfare, support and policing in the Northern Territory, passed in response to child abuse allegations—although none were ever filed. Curse and spell, Wright weaves ancient aboriginal beliefs, swooping and dipping like the swans, with fairytales and ominous “real life,” using time warps and fiercely beautiful language to register the vast environmental and social disaster that we as a people, among all others, are sure to endure.

Monica Youn’s From From; recommended by Issue 29 contributor Nicole Cooley

The book most on my mind right now is Monica Youn’s amazing poetry collection From From, published by Graywolf in 2023, which I taught this month.

We discussed the book in the Queens College MFA Program in Creative Writing and Literary Translation program, in my poetry workshop called “Series, Cycle, Sequence” in which we read and write poems that invoke and trouble the idea of the poetic sequence.

What I love most about the books I teach is when they are permission giving. Youn’s collection gives so much permission. I have now read the book many times, and it continues to be a marvel. The collection offers a wide range of forms, both fixed and invented—including studies, parables, and sonigrams. The poems investigate race and racialized identity and the body through myth and art and personal experience. Many texts and figures scaffold this book: Ovid’s Metamorphosis, Korean films and TV shows, Dr. Seuss, magpies, Crown Prince Sado. A long piece near the end, “In the Passive Voice,” explores anti-Asian hate crimes and the violences of life during the pandemic.

Monica Youn’s poems are vivid and richly imagined. And constantly surprising. In the book’s first poem, “Study of Two Figures (Pasiphae/Sado),” Youn writes: “To mention the Asianness of the figures is also to mention, by implication, the Asianness of the poet. // Revealing a racial marker in a poem is like revealing a gun in a story or like revealing a nipple in a dance.”

I love what Monica Youn’s poems reveal and also what they don’t. I love the way this book confronts the reader.

Teaching a book like From From at our current moment feels more important than ever. Higher ed is under attack, immigrants are being deported, and on my own campus, as part of the City University of New York system, students are terrified for their safety and that of their families and friends. More than 168 languages are spoken on our campus. Many of our students are undocumented. Posters about how to keep ICE off campus are being distributed. None of this is distant; it is a close reality for our campus community.

So now the idea of permission—and permission giving—takes on a different valence. Yes, this book gives enormous formal permission, but also I am thinking about something more. Something I learned from talking to my students in class about the book. Monica Youn’s poems give young writers permission to speak about the worlds around them, to write about what matters, to let a poem be a space in which anything can happen.

At this terrible moment in our history and our country, our voices and our truth-telling and our poems mean more than ever. From From is essential reading.

|

Photos courtesy of Bill Cotter. |

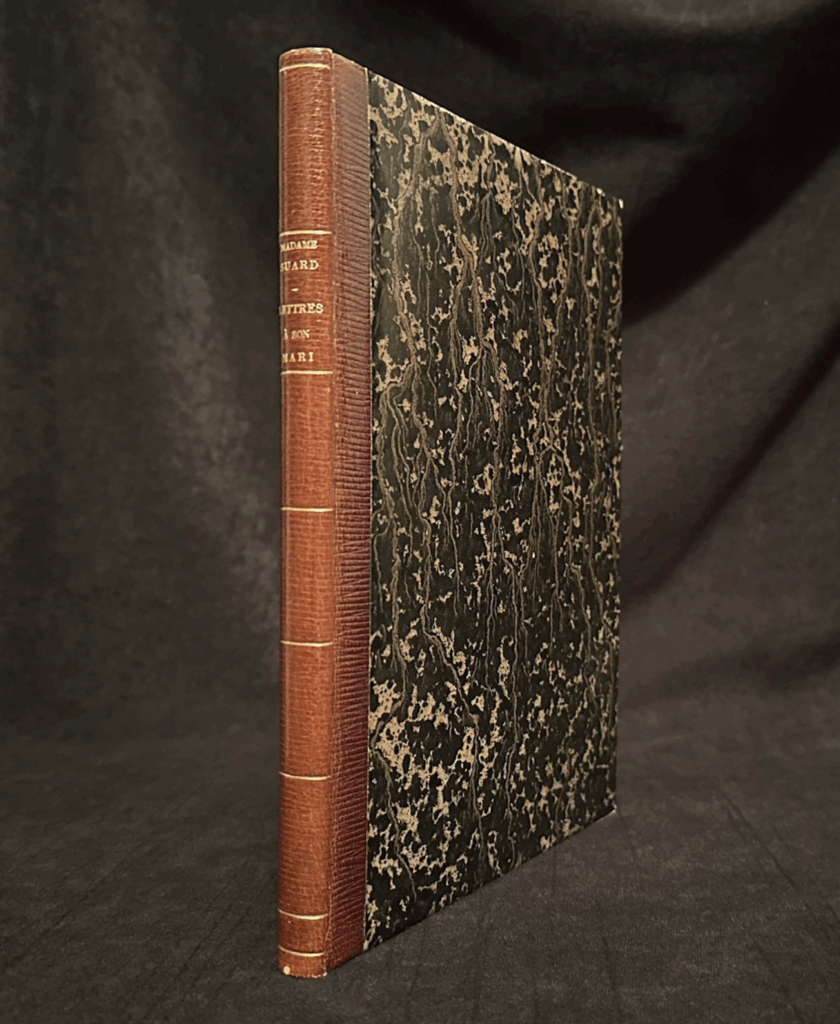

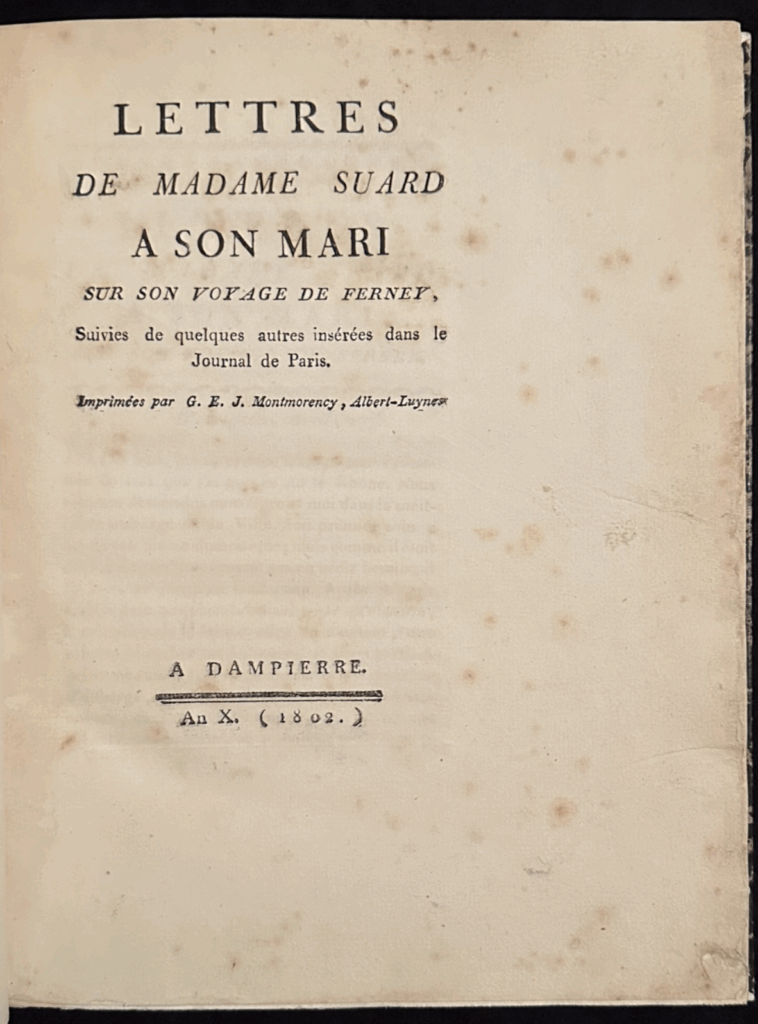

Amélie Suard’s Lettres à son mari; recommended by Issue 29 contributor Bill Cotter

One of the perks of laboring in the antiquarian book trade is the occasional opportunity to read something that hasn’t been read in a while. There are plenty of editions of Don Quixote and Fiore di virtù and Shahnameh that appear and reappear in this strange business of buying and selling old books, but now and then something truly forgotten turns up. In the last year several oddballs have come over the transom: an illustrated handbook for servants in royal Kyōto households in 1712; a four-page pamphlet recounting atrocities in Poland-Lithuania in 1561; an eyewitness account of an outbreak of plague in Piacenza in 1486; a book about werewolf attacks near Geneva in 1598. But the one that has really stuck with me is a book of letters, written by a woman upon meeting Voltaire in 1775, when he was almost 78 years old. The letters are all addressed to the writer’s husband. The first begins:

At long last I have reached the goal of my desires, and of my journey: I have seen Monsieur Voltaire. Never could even a vision of Saint Theresa surpass those what the sight of this great man made me feel: I felt I was in the presence of a god; but a god long cherished, adored, to whom I was finally given a chance to reveal my gratitude and my respect. If his genius had not led me to this illusion, his face alone would have: it is impossible to describe the fire of his eyes, nor the grace of his demeanor. What an enchanting smile!

The writer was Amélie Suard, a Paris salonneuse. Suard’s husband’s responses are not recorded, and Suard’s letters may have met with oblivion, too, had she not sought out, in 1802, her great friend, the translator and belletrist Guyonne-Élisabeth-Josèphine Montmorency-Albert-Laval, and asked her to print them. G.É.J-M.A.L, a former dame de palais at the court of Marie Antoinette, had retired to her château in the Yvette River Valley after The Terror, where she set up a handpress and a cabinet of type. Over the next eight years, she singlehandedly printed 17 books, all in very short press runs. One of the last works she printed was her friend Amélie Suard’s letters. Suard goes on to provide a unique glimpse of Voltaire as seen nowhere else, with asides on his generosity of spirit, brilliance, and probity. But Suard is no fool, and starstruck only momentarily— she expresses her wholesale condemnation of Voltaire’s misguided and extemporaneous passions, his loathing of Jews, and his stinking addiction to coffee. G.É.J-M.A.L, for her part, was obliged to stop printing in 1810, when an imperial decree outlawed private presses, bringing to an end one of the most unique printing houses in Europe, without which the letters of Mme. Suard would never have been read again.