Tiana Nobile (left) Sarah Audsley (right)

Tiana Nobile (left) Sarah Audsley (right)

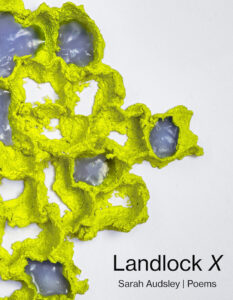

Sarah Audsley’s debut poetry collection Landlock X (Texas Review Press, 2023) is described by Sally Keith as “formally active in its interrogation; it is as if somewhere—in poetry, in art, in translation—there is a combination for righting the painful history of adoption, for learning to live simultaneously with and against.” Audsley has received support for her work from The Rona Jaffe Foundation, Vermont Studio Center, and the Banff Centre. In this interview, long-time poet-friends TIANA NOBILE and SARAH AUDSLEY discuss writing into negative space. Their intimate conversation touches on contending with audience, silences, absence, and writing from the perspective of the adoptee experience.

Tiana Nobile: In Craft in the Real World, Matthew Salesses writes: “‘Know your audience’ is craft. Language has meaning because it has meaning for someone. Meaning and audience do not exist without one another.” Who do you write for?

Sarah Audsley: Thanks so much for starting with this question. First and foremost, I write for myself, for my own way of processing lived experience, for self-discovery, for exploration, for understanding what I really think, and for many more reasons that I can’t possibly name in full. Writing, for me, is a practice, a container for feelings and thoughts. (I started keeping a journal at a young age, which was my first impulse to write). I love poems for how they allow us to engage with language, for capturing emotion, and for how they surprise us in the writing. Additionally, I write for a younger version of myself, who never read or had access to adoptee voices in literature. Finally, I write for someone else like me—another adoptee, possibly living “landlocked” in a rural place.

TN: You write in “Letter to My Adoptee Diaspora,”:

… I wonder if you long

for an unnamed touch or smell, a sense of gnawing

from the inside & if you cannot reach the surface,

then you, dear adoptee, are not alone.

I am lonely, too.

As a fellow adoptee, I’m very familiar with this flavor of loneliness. I recently learned the term, “the whipgraft delusion,” which is “the phenomenon in which you catch your reflection in the mirror and get the sense that you’re peering into the eyes of a stranger.” Does that resonate with you? How do you feel like these kinds of fissures—individual, collective, familial—impact your writing?

SA: This particular poem often makes me cringe because of its confessional moment at the end. I rarely read it in public, but when I was putting the manuscript together I knew I had to include it in the book. I think the risk of writing the sentiment outweighs the possible reward of connecting with a fellow adoptee. (Non-adoptee readers get to listen in on this moment; it’s not necessarily meant for them.) The gesture of saying, “I feel this way, do you feel this way, too?” was important to me.

What gave me courage to write the last line was Jennifer Chang’s poem, “Again a Solstice.” Chang isn’t an adoptee, but her poem resonates deeply with me.

The poem’s last lines are as follows:

What does it even mean to write a poem?

It means today

I’m correcting my mistakes.

It means I don’t want to be lonely.

I had not heard of the term “the whipgraft delusion” but I’m glad to know it now as I definitely experience this phenomenon. Isn’t it odd to have scientific or professional terms? I find it comforting to know I’m not alone, and this fact also saddens me. There are so many of us! The phenomenon is so great that there are terms!

TN: Don’t cringe! I love that moment for its vulnerability. It felt like you were reaching through the page to hold my hand. So many of your poems offer peepholes into deeply intimate scenes and reflections, and as a reader, I felt so close to your speaker, which also made the distance to X that much more pronounced. In “Confessional,” you write, “I am not enough of X.” I’d love to hear you talk about X, the relationship between X and the speaker, and how you envision the future for both.

I wanted to push against my own personal adoption experience and to gesture to the larger adoption industrial complex”

SA: The concept of the X surprised me. I can trace its inception to the poem “When My Mother Returns as X” which is an important early poem that helped me unlock the overall vision and sequencing for the book. There’s also a sentence in “Origins & Forms: Eight Sijos” that closes the sequence, emphatically and metaphorically: “I am all those mathematical distances.” Of course, the obvious reference is that X refers to the mathematical variable, which is something someone can solve for. But how do we solve for the state of adoption, of being an adoptee?

In Landlock X, the X shifts roles and can stand in for a pronoun, a speaker, an individual, an adoptee, the poet-speaker, or a collective. It tries to define itself, to solve for X, but only comes up with more questions. I wanted to push against my own personal adoption experience and to gesture to the larger adoption industrial complex.

For example in “Letter to the Woman on the Plane” the X appears to represent and hold space for the unknown number of fellow Korean adoptees:

You, who transported X number of small

squirming packages from one country to another,

of course, only remember me. I was delightful.

I did not holler the whole way on that long flight.

My intention is not for erasure, but for the variable X to stand in (or take up space) for all the unknowns, for what is undefinable, for the unsolvable. I wanted the book to have an “us” and a “we,” not just an “I.” Lately, I have been thinking about how healing—which I think is every day and on a continuum—happens in the collective.

Here is another example of how the X functions in the poem “Greenhousing”:

(X knows X can’t ask such questions). X knows

father tried to keep X

after she died, but then he put

her somewhere else

where he thought

he could remember

where he left her.

TN: It’s been my experience, too, as an adoptee poet, that searching for answers often leads to even more questions. You gesture toward this kind of historical loss in “Broken Palette :: a retrospective in panels”: “Nothing lasts. This color study is not possible without / negative space, or history”.

SA: Thanks for pointing out some of the work that “Broken Palette” is doing. As a long poem, in the second section of the book, it is a poem that takes up a lot of space. I think it can be read as seven individual poems (or panels) that are in conversation with each other. It has been helpful for me to consider my lived experience in context; my adoption story is one part, one piece of the adoption industrial complex, a system rooted in capitalism and with implications on a large scale. Writing into silences, into history or negative space, is how I tried to grapple with it all. To write a letter to my mother, which is part six of this long poem, I was surprised to find that all I could offer were silences, blank spaces, or even redactions of what phrases did come forward.

TN: How do you reckon with the impossibility of closure, in poetry and life? That is to say, when do you know a poem is “done”? When did you know the book was complete? How do we move on? (Can we?)

SA: Oh! These are great questions. First, I’ll quote Ellen Bryant Voigt who says, “It’s all a draft until you die.” I think knowing when a poem is “done” can be when the writer feels like they’ve resolved the poem’s issues, when there is surprise, or when it just “feels” done. I have been thinking a lot about what poetic closure means and the concept of “the sense of an ending.” I think this feeling of “done” can be developed over time, and also each poem or piece of writing is different and requires varied efforts and attention to its version of an ending. (I think we don’t talk enough, or at all, about how writing can be an intuitive process that one also develops over time.)

What is closure but a stepping away from, a letting go, an ending for a beginning? Perhaps, closure is just an opening”

I knew Landlock X was done when I wrote “We (or in the Blue House).” I have found it incredibly difficult to write from the first person plural, the “we” point of view. It was something that I wanted to do, but I didn’t know how to make that gesture to the collective. I didn’t want to speak for others, but I did want to connect myself to other adoptees. So, arriving at the collective “we” in the third section felt essential to the poet-speaker’s sense of selfhood. The book closes with “When My Mother Returns as X”which very well could have opened the collection. What is closure but a stepping away from, a letting go, an ending for a beginning? Perhaps, closure is just an opening.

In the following lines, I write about the absence of the mother and how she might return:

[…] She is an X

marks the spot where she made me, the hand

that never fed me, imprinting my DNA

a second time. She is a white moon tipped

over, brimming with milk for a body that’s

not there. […]

In fact, how can we resist “closure” as tying up a bow, as providing satisfaction, or as relief? I think we’re conditioned to want a tidy ending, to feel like something has been resolved. But many things never are—I don’t think I am ever going to be “done” with trying to write for my life, to exist as an invented self on the page. (Also, I believe the first-person speaker is a persona). Plus, my poetic obsessions run deep. Even this past year, trying to move past the first book, I felt like I was writing better versions of poems that could have been included in Landlock X. Which, I guess, is normal, right?

You ask: How do we move on? (Can we?) I don’t think I can move on, I don’t know how. I guess I can only write through. What I hope for is more time, more time to write, more time to be joyful. Here’s to the next poem…here’s to moving on, by going on…

Sarah Audsley is the author of Landlock X (Texas Review Press, 2023). A Korean American adoptee, a graduate of the MFA Program for Writers at Warren Wilson College, and a member of The Starlings Collective, Audsley lives and works in northern Vermont.

Tiana Nobile 문영신 is the author of Cleave (Hub City Press, 2021). She is a Korean American adoptee, Kundiman fellow, and recipient of a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award. Her writing has appeared in Poetry Northwest, The New Republic, and Southern Cultures, among others. A founding member of The Starlings Collective, she lives with her family in New Orleans, Louisiana. For more, visit www.tiananobile.com.