“The bunker was the reality of totalitarianism, its hideous remnant and reminder. The beheaded, violated, mutilated ghosts of Nicaragua bore witness, every day, to what used to happen here, and must never happen again.”

—Salman Rushdie, The Jaguar Smile

In the early hours of July 17, 1979, Anastasio Somoza snapped shut the last of his suitcases, preparing to leave. He took one last look at his newspaper; little things like pens, paper clips, and dust lay scattered around the desk, his daily mess. He’d expected this departure for days, yet he was still rushed; he was irritated and scared. In the bunker office, the stiff leather furniture and the leather-covered walls gleamed as the dim ceiling light flickered. Behind him, caught in the somber solitude of that late night of surrender, hung a large relief map of Nicaragua, the country he had “inherited” and ruled, and was now abandoning. The country whose people he had abused, tortured, waged war against. The country that was now aflame at his doorstep.

Anastasio “Tachito” Somoza Debayle was the third in a line of atrocious dictators installed in Nicaragua in the aftermath of a 1936 military coup, with the support of the United States, following their occupation of the country between 1912 and 1933. Like his father and brother before him, Tachito, or “Little Tacho,” ruled by force, tightening his grip on the destitute majority and securing his authority with the aid of the notoriously brutal National Guard. The sixties had seen the rise of various opposition movements, the largest of which was the clandestine Sandinista National Liberation Front (Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, or FSLN), inspired by the heroic deeds of Augusto Sandino, leader of the anti-imperialist nationalist guerrilla movement that combated the U.S. occupation during the thirties. The Sandinistas had taken a strong stand against the Somoza succession. Eventually, the 1978–79 revolution succeeded in bringing together a broad group of allied forces, a coalition that by July 1979 had taken definitive steps toward a transition of power. In these same rooms vacated by Somoza, the new leadership of Nicaragua would come to meet. The Junta of National Reconstruction established its headquarters in the bunker, where now, in the wake of Somoza’s departure, “a cheerful disorder ruled,” as described by writer and former Sandinista leader Sergio Ramírez in his 2011 memoir Adiós Muchachos: A Memoir of the Sandinista Revolution.

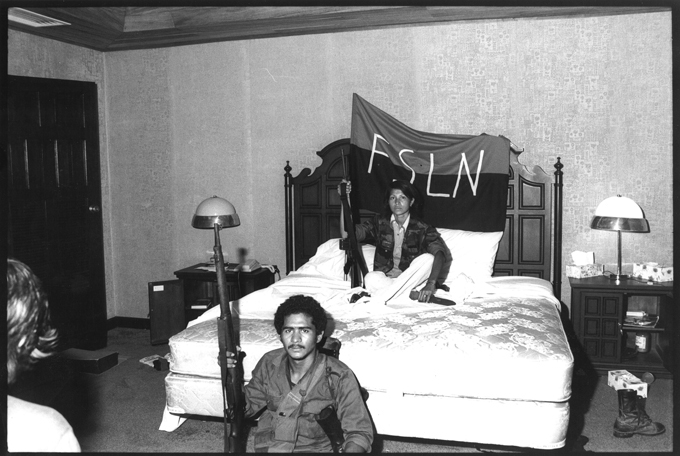

Nicaragua 1979: Sandinisten posieren auf dem Bett von Anastasio Somoza.

Copyright: Perry Kretz/Stern 1979.

Negativdatum: 22.07.1979

Archiv-Nr. 1470-001

Perry Kretz, Sandinistas posing on Anastasio Somoza’s bed, Nicaragua 1979 © Perry Kretz/Stern

El Bunker, as Somoza’s hideout was commonly known, also served as his office and main residence. At this site, two apparently contradictory spaces, domestic and military, coincided. Since it was located in close proximity to the Intercontinental Hotel in Managua, where foreign journalists and correspondents had been based since the beginning of the revolution in September 1978, photographers were close enough to document the taking of the bunker and of the adjacent National Guard headquarters, capturing images of Sandinista troops entering the offices, living rooms, and bedrooms of the dictator. In one of the most striking examples, a Sandinista “couple” pose for the picture— their stance, passionately victorious, “conquers” the bed and picture frame. The woman sits cross-legged, combat attire and shoes still on, her weapon held upright with a triumphant gesture. The man sits at the foot of the bed, repeating her gestures in an eerily exact manner. Perhaps we are witnessing some type of military exercise, a static sequence from a parade, rehearsed onto the soft, white cushion. On the headboard, the red and black striped FSLN flag lays claim to the private innermost quarters of the unseated dictator.

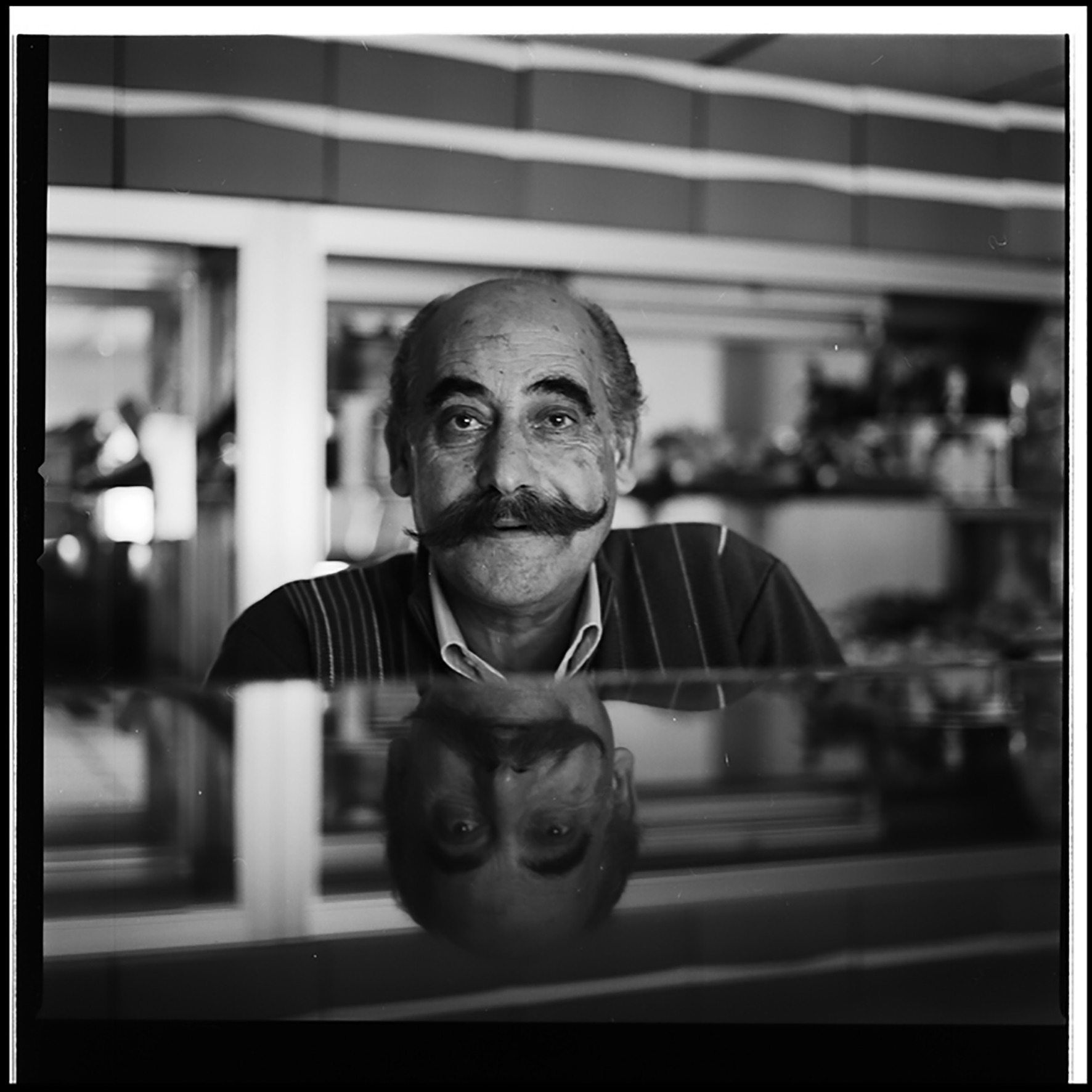

The masculine and feminine revolutionary figures stand in for the missing Somoza and his wife (or mistress), their bodies enacting the symbolic transference of legitimacy from the disgraced leader to the oppressed, power finally returned to the righteous. Taken by photographer Perry Kretz, a correspondent for the German magazine Stern, the picture appeared on the cover of Descalzos a la victoria; Barefoot to Victory, his book of photographs of the revolution published in 1980. Kretz had visited Somoza on several occasions throughout 1978–79. With every visit, he notes in his memoir Augen auf und durch! Mein Leben als Kriegsreporter (2010), the dictator—who was constantly exercising, carefully monitoring his health after an earlier heart attack—became increasingly paranoid. In the later part of the revolution, he barely left the bunker, fearing for his life. While the bedroom tableau illustrates the final overthrow of power, it also serves to articulate a powerful, iconic gesture, demonstrative of the will of a people in arms, located within a long history of imagery reaching back through the Cuban, Mexican, and French revolutions—small yet impactful gestures that would otherwise have easily gone unnoticed, as more dramatic events were taking place outside. The photographer in turn also performs a rhetorical gesture, his camera used as a weapon, communicating dissent. There it was, “the killer’s” bed, Kretz told me, sipping his espresso in the busy cafeteria at the Stern offices in Hamburg in May 2012—as if the scene was still right in front of his eyes. Similarly, Nicaraguan photographer Margarita Montealegre mentioned a few months later, in an interview we conducted in Managua, that the bedroom in disarray was one of the first, and most striking, sights she encountered upon entering the bunker, the bed and Somoza’s personal items, cosmetics, clothes, all left behind, scattered.

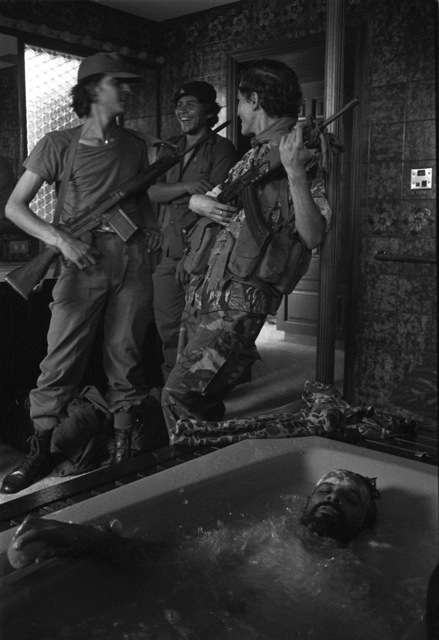

A group of pictures by photographer Pedro Valtierra, who was working on assignment for the Mexican magazine unomásuno, shows Sandinistas casually at rest on a four-poster bed in another room in the bunker, and later gathered in one of Somoza’s several luxuriously marbled bathrooms. The contact sheet shows one of theguerrilleros undressing and then soaking in the Jacuzzi tub as his companions look on.1 The later scene reminds one of the better-known photographs of Lee Miller in the bathtub in Hitler’s Munich apartment in April 1945. One might argue Miller used both the camera and her own body as a weapon, taking possession literally and figuratively of the dictator’s most private, most intimate domain. There she is, the bather, triumphantly alive, sensual, a counterpart to the classicized figurine over on the side— the scene more impactful for Miller herself, who had been a model and a muse, photographed almost obsessively by Man Ray in the nude in those abstract light-and-shadow studies from before the war. In staging the scene, Miller and fellow war correspondent David E. Scherman, who took the pictures, must have paid attention to the smallest details—how else to explain why every single one appears equally significant? From Hitler’s portrait leaning on the corner of the tub to Miller’s gaze, and from the washcloths to the monotonous patterns created by the ceramic tiles, the setting composes itself into a disconcertingly ordinary one.

Pedro Valtierra, Anastasio’s bathtub, Nicaragua 1979 © Pedro Valtierra/Cuartoscuro

Click here to view Lee Miller in Hitler’s Bathtub, via GettyImages.

Marin Raica, Nicolae Ceausescu’s former residence, Bucharest 2008 © Marin Raica.

Courtesy of the artist and Raapps Romania (Regia Autonoma Administratia Patrimoniului Protocolului De Stat).

Richard Mosse, Pool at Uday’s Palace (From the Breach Series), 2009 Digital C-print mounted to dibond.

Dimensions variable © Richard Mosse, courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York.

The strategy is reminiscent of the carefully constructed tragic interiors in the photographs of Thomas Demand, handmade scale models that reproduce architectural settings where events of historic importance, often disturbing or even atrocious, have taken place—there too the weight of the picture, content-wise, hinges on the specificity of the seemingly ordinary yet entirely piercing detail. Left by the side of the tub, Miller’s boots stain the small white rug with the mud and dirt of the devastated world outside. There are numerous examples, throughout the history of photography, devoted to the macabre subgenre of dictators’ private spaces, instances where the grand, sumptuous styles employed in the decoration of their militarized domestic interiors were exposed. Aside from the horror, there is also an uncomfortable sense of ridicule and of the absurd that comes forth so strongly through the taste for excessive decor. Whether presented in an official setting for propagandistic purposes or clandestinely obtained, such photographs continue to fascinate and appall. Newer and more easily accessible photographic technologies have brought large crowds to these sites, and have as a consequence led to the proliferation of this genre of images. A taste for the spectacular, for the fetishization of atrocious interiors and the ordinary, everyday items they contain, seems to bring together the interests of these newer publics with the dictators’ tastes. The 2011 raid on Muammar Gaddafi’s Bab al-Azizia palace and military compound in Tripoli was a powerful illustration. Upon entering the residence, opposition forces discovered one of the bedrooms that was partially destroyed during the 1986 U.S. bombing, where Gaddafi’s adopted infant daughter was killed. Like museum objects, carefully preserved, the furniture and items from the room were enclosed in glass cases. Former Sandinista Vice President Sergio Ramírez, who visited Libya in 1986 seeking support for the revolution then caught in the midst of the U.S.-supported Contra War, writes about the “tour” he received of Gaddafi’s recently destroyed house, and about seeing the bedroom in the exact condition it was left in following the attack. Among the most recent examples of dictatorial exuberance cut open for display were Saddam Hussein’s approximately eighty-four palaces in Iraq, repurposed to serve as bases for the U.S. military. Photographer Richard Mosse documented several of these spaces as part of a greater photographic project on the U.S. occupation, while embedded in 2009. Striking disruptions appear, as we notice the presence of the military scattered throughout the magnificent, opulent spaces and the lavishly decorated surfaces. We see soldiers at duty and at rest, the traces of their daily activities, screens dividing office and sleep areas, an improvised gym, barbecue grills. In one photograph, a solitary figure in uniform looks out through an oversized window frame toward a landscape flanked by the decaying, or unfinished, palace façade. In yet another scene, a squadron in full gear rests by the side of the large blue pool of the Hussein palace in the Jebel Makhoul mountains, now filled with rubble and dust. Some of the soldiers lean back, while others look out over the vast landscape in front as the Tigris River radiates toward the horizon.

Among the most powerful memories from my childhood are TV reports that featured the homes of Nicolae and Elena Ceau escu publicly exposed after their fall. Many Romanians looked in disbelief as crowds stormed the streets of Bucharest in December 1989. For years Nicolae Ceau escu smiled contently, reassuringly, from the front pages of books, on the front façades of buildings. His picture was the first to greet visitors as they entered any government or public institution. In addition, the “presidential” couple was ever present in the history textbooks, on the radio, in the newspaper, on TV. They had attempted an escape in the last days of the Revolution, but were captured and summarily executed on Christmas Day. Their residences were found to contain what at the time were described as immeasurable riches, which contrasted starkly with the overall cold, starvation, and poverty endured by the majority of the population: what further proof to seal the fate of a tragic, atrocious regime? They say Ceau escu’s rococo tastes, which combined traditional Romanian folk aesthetics with vague orientalist fantasies (Turkish baths, Persian carpets, and animal pelts), intensified after his visits to China and North Korea in 1971. Some of these belongings were most recently auctioned off in 2012.

As these views into the private quarters of dictators show, terror often lies in the most unexpected, most banal details. In an alternative reading, these common, everyday spaces and objects are transformed, haunted, by the histories that unfold around them. With the fall of authoritarian regimes, we see attempts from the public sphere (or from contending factions) to reclaim these spaces or repurpose them, taking ownership, “inhabiting” and later destroying them and the ostentatious symbolic artifacts they contain. When totalitarian regimes fall, often a purge ensues. One common strategy is the spectacular and by necessity ritualistic destruction of the captured effigies and images of the unseated rulers—markers that previously confirmed their authority. Architecture can equally become exemplarily symbolic in such dramatic conversions of power, whether spaces are transformed or destroyed. But can structures that previously served as sites of torture, suffering, abuse, incarceration, and murder ever be erased? How are traces of trauma to be finally and irrevocably removed? How far and deep do those traces go? And finally, should all traces of dictatorships be destroyed? One hopes that photography may serve not only to document but also to open up spaces for memory, for commemoration, and eventually even healing.

Ileana Selejan received her PhD from the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University, and she is currently the Linda Wyatt Gruber ’66 Curatorial Fellow in Photography at the Davis Museum, Wellesley College. Selejan wrote her thesis on thesis on the Sandinista revolution in Nicaragua, war photography, and the documentary at the turn of the eighties.

[Purchase your copy of Issue 09 here.]