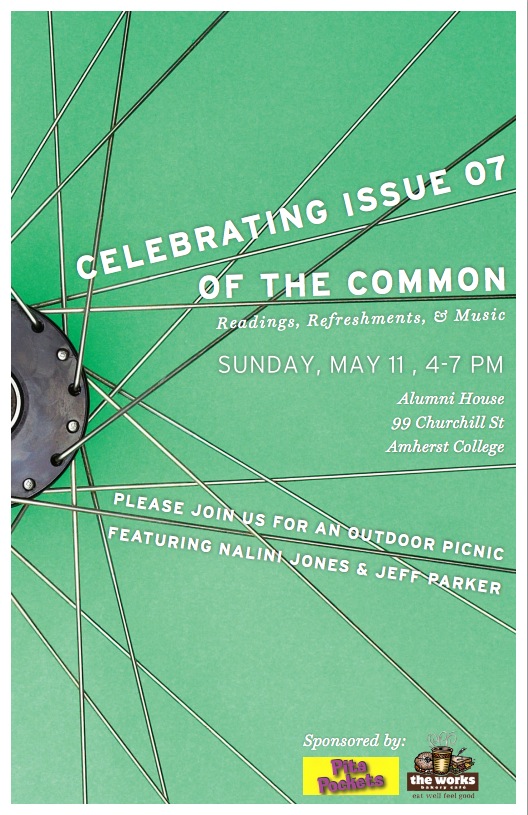

Today, we are publishing excerpts from contributors Nalini Jones and Jeff Parker in anticipation of the Issue 07 Launch Party this Sunday. Join us for a Spring fete of live literature and music featuring readings by Jones and Parker!

BUD

by Nalini Jones

for Cliff and Pete

Somewhere in the attic I have letters from Bud, typed on a real typewriter and sent to me when I was in high school and college. The letters chronicle the adventures of his terrier and on occasion were written in the dog’s voice. The dog used to wait for his chance—when the man was sleeping or when he took up his guitar in a corner of a room with a bottle and some cigarettes, maybe the beginnings of a tune. Then the dog would leap to the typewriter and start tapping the keys with small white paws.

Many of these letters were signed Bud, by the dog. My friend did not really have a dog at that time, and even the dog he imagined had some layers to him, some secrets. The imaginary dog’s real name, for example, was Rico; only his friends knew him as Bud. My friend wasn’t really named Bud either. But both were Red Sox fans, a point that is emphasized in the letters. It was well known by man and dog that my father was a Red Sox fan too.

Surely I could find these letters, if I looked, tucked into stacks that are sorted by year or gathered into a bundle of Bud correspondence, tied, perhaps, with ribbon or string. They began when I was thirteen and Bud was in his thirties, shortly after I heard him play three songs in a revolving-door set with some other folk musicians, old and new. My dad was one of the older ones; he no longer played anymore, except to us, his family. Bud was one of the new ones. I can’t believe I pissed my twenties away, he sang. When the concert ended, he went back to writing songs, and I went back to middle school, and we wrote letters across those twenties. He couldn’t believe his were over; I didn’t think mine would ever arrive.

There was a lot for a bookish kid to admire in those letters. I was delighted by the connection between Rico’s paws on the keys and the literary efforts of Archy the cockroach and Mehitabel the cat. Had Bud read those poems too? I never asked. I think I assumed he’d read everything, knew it all. Descriptions of Rico, drunk with sensation at the wheel of Bud’s car in Harvard Square, seemed uncannily like Flush first encountering the scents of Italy. But if the idea of Bud curling up with Virginia Woolf strained credulity, it was easy to associate Rico’s doleful wisdom with the giants of Russian letters, whose staunch sadness found an unlikely echo in Red Sox fans of the early 1980s. I also appreciated the dog’s Yankee spirit, his get-rich-quick schemes, his plans to support the struggling folk singer by conceiving of celebrity endorsements for him. Bud obliged. “Vodka,” he liked to intone. “It’s not just for breakfast anymore.”

Best of all, the deft wit of the letters was a beacon of possibility in my world, where humor was broadly understood as a collective agreement to laugh when, light as a feather, stiff as a board, someone at Peggy Ryan’s slumber party could be induced to kiss a pillow, or when our chorus teacher, Miss Luttenegger, was suspected to have a boyfriend.

Since I myself was never the subject of such speculation, I was painfully alive to the generosity of Bud’s letters. I knew who I was, with my stick limbs and thin hair and all the wrong clothes, or the wrong way of wearing them. Why did he befriend me? Did he make a habit of being nice to kids? Was he trying to keep in touch with my dad, who would soon bring back the big Festival? Was he already lonely? I just set off down the road alone, but it’s always gone that way.

“He liked smart people,” his friend C. said. “He liked to surround himself with people who were smart. He did it all his life.”

But I have no idea what a kid could have written that was smart enough to interest him. I think what mattered most to Bud is that I liked him. He didn’t have to wonder if I’d write back. I was a spindly little bookworm with glasses. What else did I have going on?

My guess is that Bud also appreciated what I already knew. I’d spent years trailing after my father, backstage at stadium shows, in the wings of jazz festivals, folded into poky corridors of folk clubs. I knew what Bud and his friends were trying to do, and I knew it wasn’t easy: the long hours, the bad meals, the hard chairs when you needed to nap, the hand towels when you needed a shower. They worked hard, and their work was fractured into pieces so contradictory that it sometimes seemed crazy to try to gather all those jangling parts back together into a single person. They had to make money, and they had to make art. They had to cope with isolation on the road and with the constant churning upheaval of meeting new people. They had to find solitude to write, and they had to court audiences to play. They had to win fans, and they had to hold fans at bay. They had to navigate a ruthless business, and they could not afford to seem too slick. They had to write and they had to sing and they had to play an instrument and they had to record. They had to find a way to be funny while they tuned their guitars. And their ambitions had to be crafted as carefully as their songs: a better advance, a major label, some radio play—maybe a song that caught the public unaware. They were dreamers who couldn’t dream too big.

When I met Bud and his friends, they were all surge and courage. They were smart and funny and present; they wrote with care and passion; they had the beginnings of a following. They weren’t all going to be stars, but their endeavor moved me, the same way I was moved by the Ray Charles Band, arriving on a low-budget bus hours before Ray himself swept onsite in a town car. I’d been raised to champion the ones who weren’t stars. I was ready to make Bud a hero.

Bud was in no state to object. Confidentially, Rico conceded, there was a downside to Bud’s impending divorce—it darkened the mood, though he himself, a spry terrier, was too lively to succumb to low spirits. And Bud was not the only one who’d suffer. Sure, she’s the one walking out the door, he conceded. But you don’t think she’ll miss the big time? The tuning, the trail mix, the single-drink ticket. Once you get used to that life, it’s hard to give up. In the end, Rico took the long view, a managerial squint in his terrier eye. Songs were gathering like storm clouds, and everyone knew the power of a divorce album.

I’d met the first wife. I sat next to her at a concert once and watched her face when Bud sang, Hey, my little darlin’—a song for her. Round and round and round we go. It was as lively as Bud could be, but his wife didn’t move; she didn’t even smile. Why? I wondered, feeling she ought to. She sat, hardening like poured cement, and the song ended. A new one began. I stopped thinking about her. And if it hadn’t-a been for whiskey, I never would’ve made it through our first few years. I was a kid, not always alive to subtext. It didn’t occur to me she was in that song too.

Bud’s friend P. has unearthed the letters Bud wrote to him, letters in the voices of two old blues guys, Lemon and Bud (in which P. is Bud and Bud is Lemon). P. transcribed the whole correspondence, scathingly irreverent, and forwarded me a copy. P. said, “I don’t think I can really show this to people.”

I have not yet gone into the attic to look for my bundle of letters, undoubtedly preserved—among the yearbooks and old festival programs—through the nine times I have moved since our correspondence began. I have not unearthed the photos of Bud singing the first song at my wedding, which someone has surely recorded, though we were not the types to hire a videographer. And maybe this is that town where there’s no goodbye. I have not yet erased Bud’s number from my phone.

FROM SANKYA

by Zakhar Prilepin

Trans. Jeff Parker

That winter they hired a small bus—Mother had suggested that Father should be buried in the village. Where he was born.

Sasha hadn’t argued.

“What do you think, son?” asked Mother in a completely unfamiliar tone. Until then, there had always been a man’s voice that had the final word in the house. Now, that voice was dead.

“We’ll get there somehow,” Sasha answered, though he was almost certain that they would not be able to get there. Anyway they couldn’t bury Father in this decrepit town, a place that Sasha had always loathed.

And Sasha couldn’t imagine telling his grandparents in the village of his father’s death, knowing that not only would they be unable to travel to the funeral, they would be unable to visit their son’s grave until the spring came.

They didn’t properly explain anything to the driver—had he known where they were going, he would have said no right away. He was told, “Just head out of town…. We’ll show you the way….” He didn’t ask, “Out of town where exactly?” He was a modest type of guy and seemed, at first, even-tempered.

Father’s friends, a few professors, and some students came to say goodbye. Every single one of the well-wishers offering their condolences made Sasha want to hurl them down the stairs. To hell with your condolences. You don’t understand anything.Sasha avoided all of them, didn’t want to see a single one.

He happened to hear his mother ask: “Maybe someone would like to come to the funeral with us?”

The silence that followed was nauseating.

Somebody said apologetically, “Work….”

“I will,” one man said. It was Bezletov.

Nalini Jones is the author of a story collection, What You Call Winter, and other short fiction and essays.

Zakhar Prilepin was born in 1975 and is one of Russia’s most acclaimed and widely translated contemporary authors.