By CHARLES YU

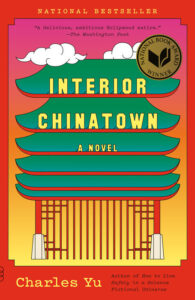

Amherst College’s sixth annual literary festival will take place virtually this year, from Thursday, February 25 to Sunday, February 28. Among the guests are 2020 National Book Award fiction winner Charles Yu and longlist nominee Megha Majumdar. The Common is pleased to reprint a short excerpt from Yu’s novel Interior Chinatown here.

Join Megha Majumdar and Charles Yu in conversation with host Thirii Myo Kyaw Myint (visiting writer at Amherst College) on Friday, February 26 from 7 to 8pm.

Register and see the full list of LitFest events here.

ACT I

INT. GOLDEN PALACE

INT. GOLDEN PALACE

Ever since you were a boy, you’ve dreamt of being Kung Fu Guy.

You are not Kung Fu Guy.

You are currently Background Oriental Male, but you’ve been practicing.

Maybe tomorrow will be the day.

INT. GOLDEN PALACE

Ever since you were a boy, you’ve dreamt of being Kung Fu Guy.

You are not Kung Fu Guy.

You are currently Oriental Guy Making A Weird Face, but you’ve been practicing.

Maybe tomorrow will be the day.

|

You take what you can get.

You try to build a life.

A life at the margin

made from bit parts |

WILLIS WU

(ASIAN) ACTOR

Resume/Skills:

Working on Kung Fu

Proficient in Moderate Asian Accent

Repertoire:

Disgraced Son

Delivery Guy

Face of Great Shame

Henchman

Caught Between Two Worlds

Guy Who Runs in and Gets Kicked in the Face

Striving Immigrant

Generic Asian Man

Your mother has played, in no particular order:

Pretty Oriental Flower

Asiatic Seductress

Young Dragon Lady

Slightly Less Young Dragon Lady

Restaurant Hostess

Girl with the Almond Eyes

Beautiful Maiden Number One

Dead Beautiful Maiden Number One

Old Asian Woman

Your father has been, at various times:

Sifu, the Mysterious Kung Fu Master

Twin Dragon

Wizened Chinaman

Inscrutable Shopkeeper

Guy in a Soiled T-Shirt

Inscrutable Grocery Owner

Inscrutable Grocery Owner in a Soiled T-Shirt

Egg Roll Cook

Old Asian Man

INT. GOLDEN PALACE – MORNING

In the world of Black and White, everyone starts out as a Generic Asian.

You all work at Golden Palace, formerly Jade Palace, formerly Palace of Good Fortune. There’s an aquarium in the front and cloudy tanks of rock crabs and two pound lobsters crawling over each other in the back. Laminated menus offer the lunch special, which comes with a bowl of fluffy white rice and choice of soup, egg drop or hot and sour. A neon Tsing Tao sign blinks and buzzes behind the bar in the dimly lit space, a dropped-ceiling room with lacquered ornate woodwork (or some imitation thereof), everything simmering in a warm, seedy red glow thrown off by the dollar store paper lanterns festooned above, many of them darkened by dead moths, the paper yellowing, ripped, curling in on itself.

The bar is fully stocked with top shelf spirits up top, middle shelf liquor at eye-level, and down at the bottom, happy hour shelf of booze that you will regret for sure. The new thing everyone is excited about is called the lychee margaritatini, which seems like a lot of flavors. Not that you’ve had one. They’re fourteen bucks. Sometimes people leave a sip at the bottom of the glass and if you’re quick, while you go through the swinging door that separates the front of the house from the back, you can have a taste—you’ve seen some of the other Generic Asian Men do it. It’s a risk, though. The manager’s always got an eye out, ready to fire someone for the smallest infraction. People come to Golden Palace for the experience, he says. You have to give them what they want.

You wear the uniform: white shirt, black pants.

Black slipper-like shoes that have no traction whatsoever. Your haircut is not good, to say the least. Turner and Green always look good. It doesn’t seem possible for them to not look good. A lot of it has to do with the light, you understand, but that’s the point. Turner and Green, Black and White, they get the hero lighting. Designed to hit their faces just right. Someday you want the light to hit your face just right. To look like the hero. Or just for a moment to actually be the hero.

First, you have to work your way up. Starting from the bottom, it goes:

5. Background Oriental Male

4. Dead Asian Man

3. Generic Asian Man Number Three/Delivery Guy

2. Generic Asian Man Number Two/Waiter

1. Generic Asian Man Number One

and then if you make it that far (hardly anyone does) you get stuck at Number One for a while and hope and pray that the light will find you and that when it does you’ll have something to say and when you say that something it will come out just right and everyone in Black and White will turn their heads and say wow who is that, that is not just some Generic Asian Man, that is a star, maybe not a real, regular star, let’s not get crazy, we’re talking about Chinatown here, but perhaps a very special guest star, which is the terminal, ultimate, exalted position for any Asian working in this world, the thing every Oriental Male dreams of when he’s in the Background, trying to blend in.

Kung Fu Guy.

Kung Fu Guy is not like the other slots in the hierarchy—there isn’t always someone occupying the position, as in whoever the top guy is at any given time, that’s the default guy who gets trotted out whenever there’s kung fu to be done. There has to be someone worthy of the title. It takes years of training, and even then, only a few have even a slim chance at making it. Despite the odds, you all grew up training for this and only this. All the little yellow boys up and down the block dreaming the same dream.

INT. GOLDEN PALACE

Ever since you were a boy, you’ve dreamt of being Kung Fu Guy.

You are not Kung Fu Guy.

You are currently Generic Asian Man Number Three/Delivery Guy.

Your kung fu is B, B plus on a good day, and Sifu once proclaimed your drunken monkey to be nearly at a level of competence that he could perhaps at some point in the future imagine not being completely embarrassed of you. Which if you know Sifu, well, that’s a pretty big deal.

To be honest, though, it’s hard to tell with Sifu, who is famously inscrutable. If you could show him what you’ve become. If you could make him proud. All you want is for him to make that face, the one that looks like internal distress possibly of a gastrointestinal nature but actually indicates something closer to Deeply Repressed Secret Pride Honorable Father Has For His Young But Promising Son. That’s how you see it in your head: he would make that face, smile, you’d smile back. Credits roll and you’d walk off, arm-in-arm, to the horizon.

Last time you saw him as Sifu was a little over a year ago. Or was it five? You used to mark time by days on the job, but lately they’re all starting to run together.

That morning you showed up a few minutes early for your weekly lesson. Maybe that’s what threw him off. When he answered the door, it took him a moment to recognize you. Two seconds, or twenty, a frozen eternity—then, as he regained himself, his familiar scowl, barking your name

WILLIS WU!

half-exclamation, half-confirmation, as if verifying for both you and himself that he hadn’t forgotten who you were. Willis Wu, he said again, well come on, what are you doing, don’t just stand there in the doorway like a dum-dum, come in, son, come in, let’s get started.

He was fine for the rest of that day, mostly, but you couldn’t stop thinking about the look he gave you, whether it was oblivion or terror, and for the first time you noticed the mess his room had become, not unusual for any other man his age living alone, but for Sifu, who taught and valued order and simplicity in all things, to have allowed his dwelling to reach this state of disorganization was a warning sign, should have been a warning sign to all. Maybe not the first, but the first one that came to your attention.

Fatty Choy went around telling everyone that Sifu was on food stamps, saying how gullible can you be (“You idiots think being Wizened Chinaman pays well? Are you crazy? Why do you think he fishes bottles and cans out of the trash?”) but no one wanted to believe it. At least in public. In private, the thought did occur. Sifu never had the lights on. Said it was to train the senses. He saved everything: disposable chopsticks, free glossy calendars from East-West Bank (“good for wrapping fish or fruit”), packets of soy sauce and chili paste from the dollar Chinese down the street. He’d patched his old fake leather couch so many times there were cracks on the patches. Which of course he also patched. The formica two-top he ate on was the first and only kitchen table he’d ever bought, purchased for seven dollars and fifty cents from the salvage bin at the old restaurant supply warehouse down on Jackson and Eighth, that place long gone now (converted to INT. RAVE/GRIMY CLUB SCENE) but the table still there in the kitchen. An artifact of the previous century, it had worn down to a smoothness so comforting and cool it felt soft to the touch, the patterns of use, hundreds, thousands of meals together in the corner of that small, low-ceilinged room, the surface preserving the teachings of Sifu, wisdom over time recorded in the warp and wear, in the patterns of the modest table itself. Come to think of it, Fatty Choy, despite the fact that he was and had always been a total gasbag, a mostly insufferable close-talking blowhard (made all the more insufferable by the fact that he was not infrequently right about things) was simply stating something you all kinda knew but didn’t like to talk about: Sifu had gotten old.

It was easy to lie to yourself about it. Although naively you believed he had miraculously never gone gray, in hindsight you remember once seeing an empty box of natural seaweed coloring in his wastebasket, Sifu emerging from his room with the occasional smear where he’d gotten a little careless and ended up painting the top edge of his forehead a swath of kelpish green.

And even if he could still break a cinder block with three fingers, that was nothing compared to back in the day, his younger self, when he could do it with just one finger—a single powerful blow of any digit. You pick! You always picked the thumb and then couldn’t bear to watch, peeking through your fingers when you were little and as you got older still wincing in the expectation of painful failure, but the thing is, he never failed. Never. He always found the necessary reserves of chi, always was able to summon forth from whatever intangible reservoir the required force to smash through it, and everyone gathered around would clap and shout their praise at this demonstration of Sifu’s mind over matter, mental and physical, an impossible feat right there in the alley behind the kitchen in the middle of a Tuesday. You’d uncover your eyes with relief, and exhale, proud, and grateful that he done it once again, hadn’t mangled his hand, and also slightly ashamed that you’d doubted him at all, hadn’t believed in him, his own son having less confidence in Sifu than the assembled friends and strangers.

Your earliest memories of him as a young dragon, a rising star, his thick straight hair the color of night and combed slowly and carefully straight back in a thick, lustrous wave. His forearms like steel barrels lifting you out of the makeshift playpen in the corner of the room and flying you around up above his head, almost crashing into the bed and the lamp and the ceiling as you laughed and laughed until your mother said xiao xin, xiao xin, that’s enough, Ming, please, stop before he gets sick, and then he’d put you down safely, your feet touching the ground, the world still spinning.

Whether we admitted to it or not, and sometimes you did admit it to yourself, right before falling asleep, in the way thoughts like this come to you: your first, best, and only real master, the source of all our kung fu knowledge, was no longer himself. He’d aged out of his role and into the next one, his life force depleting with every exertion. Wisdom and power leaking from him with each passing day and night. He’d played his role for so long he’d lost himself in it, before some separation that happened gradually over decades and then you waking one day to feel it, some distance that had crept in overnight. Some formal space you could no longer cross.

He’d always be Your Father, but somehow was no longer your dad.

No longer running up walls, no more leaping from the curved roof eaves of the Bank of America pagoda. More often found nodding off during a meal, eaten alone, in front of the six o’clock news. Long after you’d graduated into an adult role, you still continued coming to him for these weekly lessons, but the lessons had turned into a flimsy pretense layered atop their real purpose: your delivery of provisions on which your old man depended. A few groceries, toilet paper, his various prescriptions. Putting things out so they’d be easy to access for him, wiping the floor as best you could. There was only so much time. Checking for dampness on his mattress pad, changing it if necessary, picking up laundry, sweeping from his nightstand the accumulation of balled-up napkins enclosing clots of dried phlegm and blood. More napkins behind the nightstand and all around, a half-eaten pear under the formica table, there since the day after your last visit, having dropped and rolled to a stop right in that very spot, left to slowly rot, the gentle descent into squalor not a function of sloth but simple, physical inability.

I’m sorry. I can’t reach. I’m sorry.

No sorry, no need for sorry.

Okay. I’m sorry.

The apologies, broken and small, the true sign—that this was not the same man, not the man you once knew, a man who would never have uttered that word to his son, sorry, sorry, and in English, no less. Not because he thought himself infallible, but because of his belief that a family should never have to say sorry, or please, or thank you, for that matter, these things being redundant, being contradictory to the parent-son relationship, needing to remain unstated always, these things being the invisible fabric of what a family is.

You did what you could despite being generally ignored except for the occasional, mumbled, embarrassed non-apology, Sifu-now-Old-Asian-Man having forgotten not just his kung fu technique but also his most loyal student, regarding you with a blank if slightly wary amiability, as one might endure an overbearing but helpful stranger. Your relationship having turned into a pantomime, a series of gestures in a well-worn scene, played out over and over again, any underlying feeling having long since been obviated by emotional muscle memory, of learning how to make the right faces, strike the right poses, not out of apathy or lack of sincerity, rather a need to preserve what was left of his pride.

The trick was learning what not to say. To enter the theatre of his dotage quietly, sit there in the dark and not ask him any question, however simple, that might cause momentary confusion, might turn your rote interactions into something too raw, remind yourselves or each other of what was happening here, the inversion of the relationship, the care and feeding, the brute fact of physical dependency: if you don’t do this, he can’t do it for himself. If you miss a week, he sits in the dark.

Not that he’ll die. Although there is always that possibility.

But he’ll be lonelier that day, hungrier. He’ll lose something or drop something or break something and have to wait for you to call or come by.

Staying in character avoided all of that, allowed you to prolong your respective roles for just a bit longer, and in a good week, when things were going along relatively well, you could get by, could walk through your blocking and lines, make it to the end of the day. But on bad days or if you’d stay too long, his patience or working memory would reach its limit, and he’d edge into a twilight distrust, fear in his eyes.

Even on the worst days, he never completely forgot you for more than a minute or two—somehow in his paranoia you sensed he always knew that you were someone to him.

In the months since, he eventually settled into a new, diminished equilibrium, even began to work again, as Old Asian Cook or Old Asian Guy Smoking, which was rough, was a hard thing to see for anyone who’d known him back when. Known what he’d been capable of. A new role, a new phase of life, it could be a way of starting fresh, the slate wiped clean.

But the old parts are always underneath. Layers upon layers, accumulating. Which was the problem. No one in Chinatown able to separate the past from the present, always seeing in him (and in each other, in ourselves), all of his former incarnations, the characters he’d played in our minds long after the parts had ended.

In that way, Sifu had gotten this old without anyone noticing. Including your mother—deemed to have aged-out of her Asian Seductress, nor longer Girl With The Almond Eyes, now just Old Asian Women—now living down the hall, their marriage having entered its own dusky phase, bound for eternity but separate in life, the rationale being that she needed to continue to work in order to be able to support him and for that she needed a minimum amount of rest and peace of mind, all true, and that they were better apart than together, also true. The reality being that they’d lost the plot somewhere along the way, their once great romance spun into period piece, into an immigrant family story, and then into a story about two people trying to get by. And it was just that: getting by. Barely, and no more. Because they’d also, in the way old people often do, slipped gently into poverty. Also without anyone noticing.

Poor is relative, of course. None of you were rich or had any dreams of being rich or even knew anyone rich. But the widest gulf in the world is the distance between getting by and not quite getting by. Crossing that gap can happen in a hundred ways, almost all by accident. Bad day at work and or kid has a fever and or miss the bus and consequently ten minutes late to the audition which equals you don’t get to play the part of Background Oriental with Downtrodden Face. Which equals, stretch the dollar that week, boil chicken bones twice for a watery soup, make the bottom of the bag of rice last another dinner or three.

Cross that gap and everything changes. Being on this side of it means that time becomes your enemy. You don’t grind the day—the day grinds you. With the passing of every month your embarrassment compounds, accumulates with the inevitability of a simple arithmetic truth. X is less than Y, and there’s nothing to be done about that. The daily mail bringing with it fresh dread or relief, but if the latter, only the most temporary kind, restarting the clock on the countdown to the next bill or past due notice or collection agency call.

Sifu, like many others INT. CHINATOWN SRO, had without warning or complaint slid just under the line, so quietly, so casually, it was easy to minimize how painful it must have been. The pain of having once been young, with muscles, still able to work. To have lived an entire life of productivity, of self-sufficiency, having been a net giver, never a taker, never relying on others. To call oneself master, to hold oneself out as a source of expertise, to have had the courage and ability and discipline that added up to a meaningful, perhaps even noteworthy life, built over decades from nothing, from almost nothing, and then at some point in that serious life, finding oneself searching for calories. Knowing what time of day the restaurant tosses its leftover pork buns. Not in a position to turn down any food, however obtained, eyeing the markdown bins in the ninety-nine cent store, full of dense, sugary bricks and slabs and disc-sized cookies, not food really, really only meant for children, something to fill the belly of a person who once took himself seriously.

And then buying this food, without hesitation, necessity overcoming any shame in simply eating it, and not just eating it, swallowing it down more quickly than intended, a young man’s dignity replaced by a newly acquired clumsiness, the hands and mouth and belly knowing what the heart and head had not yet come to terms with: hunger. Real hunger. Not metaphorical, not existential. Animal hunger. Empty stomach hunger.

Doing this alone in a crowd, living solitary but cramped, yards away from neighbors. Just down the hall, well-meaning others who in theory could help, but in practice somehow never manage to, a failure arising not out of apathy or lack of compassion. Rather, surprise—as if everyone were paralyzed at how things had turned out, that even for the best, the decline always comes and sooner than you think. Not quite believing, friends and relatives and everyone else in the building spending months or even years in a sort of slow-motion denial, gossiping (“Sifu has trouble getting down the stairs” or “the other day I saw him eating day old discounted lunch meat by himself on a bench outside the market”), taking their time adjusting to the idea. No one knowing how to deal with it until it was a little too late to properly deal with it, least of all the person it was happening to.

To be fair, it wasn’t as if anyone in Chinatown was in a great monetary position to be helping Sifu. Old Asian Woman did what she could, but as work slowed down, was having enough of a challenge trying to take care of herself. And you just starting out, contributing what you could manage, a bag of food or medicine, once in a while a piece of fish or meat. That’s what you tell yourself anyway. The truth being that if each of you had done a little, together it might have been enough.

Then again, collection would only be one part of it, however. The easy part. The hard part would require a feat even more impossible than defeating Sifu in combat—convincing him that he needed help, to find a way he could accept charity while allowing him to retain his dignity.

Some say that the person who should have helped the most, was in a position to help the most, having been Sifu’s number one-most-naturally-gifted-kung-fu-superstar-in-training-pupil all those years and thus having reaped the greatest benefit from Sifu’s teachings, was Older Brother.

The prodigy. The homecoming king. Unofficial mayor of the neighborhood. Guardian of Chinatown.

Once the heir apparent to Sifu, the two of them even starring together in a brief but notable project about father and son martial arts experts (Logline: when political considerations make conventional military tactics impossible, the government calls on a highly secretive elite special ops force—a father-son duo among the best hand-to-hand fighters in the world—in order to get the job done, Codename: TWIN DRAGONS).

Older Brother who never had to work his way up the ladder, never had to be Generic Asian Man. Older Brother who was born, bred and trained to be, and eventually did become, Kung Fu Guy, which meant, of course, making Kung Fu Guy money, which is good for your kind but still basically falls under the general category of secondary roles.

But Kung Fu Guy money certainly would have been enough to keep a hundred and eight pound Wizened Chinaman in rice and pickles and the occasional bottle of beer for a few golden years of retirement. The idea of Sifu taking charity—taking groceries—from anyone would have been hard to swallow, but if someone could have done it, it was the chosen one, the golden boy of Golden Palace.

Older Brother.

Like Bruce Lee, but also completely different.

Lee being legendary, not mythical. Too real, too specific to be a myth, the particulars of his genius known and part of his ever-accumulating personal lore. Electromuscular stimulation. Ingesting huge quantities of royal jelly. And with his development of his own discipline, jeet kune do, the creation of an entirely new fighting system and philosophical worldview. Bruce Lee was proof: not all Asian Men were doomed to a life of being Generic. If there was even one guy who had made it, it was at least theoretically possible for the rest.

But easy cases make bad law, and Bruce Lee proved too much. He was a living, breathing video game boss-level, a human cheat code, an idealized avatar of Asian-ness and awesomeness permanently set on Expert difficulty. Not a man so much as a personification, not a mortal so much as a deity on loan to you and your kind for a fixed period of time. A flame that burned for all yellow to understand, however briefly, what perfection was like.

Older Brother was the inverse.

Not a legend but a myth.

Or a whole bunch of myths, overlapping, redundant, contradictory. A mosaic of ideas that never quite fit together, a thousand and one puzzle pieces that teased you, let you see the edges of something, clusters here and there, just enough to keep hope alive that the next piece would be the one, the answer snapping into place, showing how it all fit together. Bruce Lee was the guy you worshipped. Older Brother was the guy you dreamt of growing up to be.

[Buy Interior Chinatown here.]

Excerpted from Interior Chinatown by Charles Yu. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

Charles Yu is the author of How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, Sorry Please Thank You, and Third Class Superhero and worked as a storyboard editor on Westworld. He received the National Book Foundation’s 5 Under 35 Award and was a finalist for the PEN Center USA Literary Award. His work has been published in The New York Times, Playboy, and Slate, among other periodicals. Yu lives in Los Angeles with his wife, Michelle, and their two children.