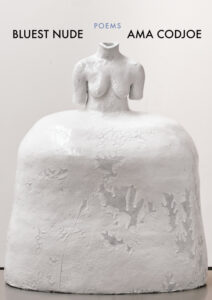

Ama Codjoe is the author of Bluest Nude (Milkweed Editions, 2022) and Blood of the Air (Northwestern University Press, 2020), winner of the Drinking Gourd Chapbook Poetry Prize. Her recent poems have appeared in The Nation, The Atlantic, The Best American Poetry series, and elsewhere. Among other honors, she has received a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writer’s Award, a Creative Writing Fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, a NYSCA/NYFA Artist Fellowship, and a Jerome Hill Artist Fellowship. She lives in New York City.

Table of Contents:

- Of Being in Motion

- On Seeing and Being Seen

- Bluest Nude

Of Being in Motion

There’s a body marching toward mine.

I can feel its breasts and stomach, hot

against my back. Its breath in my hair.

I accumulate bodies—my own.

The tattoo braceleting my wrist.

My earlobe like a pin hole camera.

My vagina, untouched. My vagina,

stretched. So many bodies treading

toward the others. And the bruises I conceal

with makeup and denial. The scars I inflict

on myself, and the ones I contort

with a mirror to see. I didn’t always know

we’d be joined like this—that I couldn’t

leave any of myself behind.

In Trisha Brown’s Spanish Dance

a performer raises both arms like a bailora

and shifts her weight from hip to hip, knee

to knee, ankle to ankle, until she softly

collides with another dancer. The two travel

forward, pelvis to sacrum, stylized fingers

flared overhead, until they meet a third woman

and touch her back like stacked spoons.

Dressed in identical white pants and long

sleeves, the dancers repeat the steps

until, single file, five women shuffle

forward—they go no further.

The dance lasts the exact length of Bob Dylan’s

rendition “Early Mornin’ Rain.”

How many versions of myself pile

into the others, arms lifted in surrender,

torsos twisting to the harmonica?

But the dancers—I’m moved by their strange

conga line. A train of women traversing

the stage, running gently into a wall.

On Seeing and Being Seen

I don’t like being photographed. When we kissed

at a wedding, the night grew long and luminous.

You unhooked my bra. A photograph

passes for proof, Sontag says, that a given thing

has happened. Or you leaned back to watch

as I eased the straps from my shoulders.

Hooks and eyes. Right now, my breasts

are too tender to be touched. Their breasts

were horrifying, Elizabeth Bishop writes. Tell her

someone wanted to touch them. I am touching

the photograph of my last seduction. It is as slick

as a magazine page, as dark as a street

darkened by rain. When I want to remember

something beautiful, instead of taking

a photograph, I close my eyes.

I watched as you covered my nipple

with your mouth. Desire made you

beautiful. I closed my eyes.

Tonight, I am alone in my tenderness.

There is nothing in my hand except a certain

grasping. In my mind’s eye, I am

stroking your hair with damp fingertips. This is exactly

how it happened. On the lit-up hotel bed,

I remember thinking, My body is a lens

I can look through with my mind.

Bluest Nude

1.

When my mother was pregnant, she drove

every night to the Gulf of Mexico.

Leaving her keys and a towel on the shore,

she waded into the surf. Floating

naked, on her back, turquoise waves

hemming her ears, she allowed

the water to do the carrying. It isn’t

true. My mother lived hours inland

and her doctor prescribed bed rest. I want her

to be weightless, belly up and moon-lit

or filling a bathtub with hot water and stepping

gingerly, so as not to slip, easing herself

into the cramped tub, rimmed

with dirt from her husband and son,

soaking for as many minutes as she could,

savoring the water as it turned cold.

2.

In the news, there was another

incident . . . If I describe how

the officer treated

the young woman’s body,

I am also describing

the color of her body.

Let me refuse simile.

I do not wish to write it.

3.

In the flower of my body—

blossoms belonging,

at last,

to me,

sovereign

place, where I am no one

but myself: peony and cracked vase,

weeping beech and spiraled shell,

siren, matron, Jezebel—

a rush of bees enters me,

and I am not stung;

petals unfold in night’s

bluest hymn.

4.

The blue swimming pool. The blue

in a record’s groove, revolving.

The pink hydrangea turned

powder blue. Glory-of-the-snow

blue. Blue-black blue. The blue

of a bruise. Wild blueberry

blue. The blue you pick. The blue

you choose. The blue that bucks us

like a bull. The blue bowl full

of lilacs. The blue that falls

as tufts of hair from the barber’s

chair. The blue sun makes.

The blue shade of a yellow pine.

Television blue. Cadmium blue.

Blue twisted into the spools

of your DNA, forking into two

directions. Blue darkening

your knees. The blue you miss

because—though it almost

killed you—blue was,

for a season, your home.

5.

There was another . . . incident.

If I describe how the officer treated

the young woman’s body, I am also

describing the color

of my body.

6.

Then the last piece, a solemn veil lifted

and tossed to the floor. I know the history

of my body is a pair of hacked off hands

playing the piano. Day after day in the artist’s

studio, I smell the melon’s ripe decay.

I draw a second body, then a third, and so on.

My bodies reveal nothing and conceal

nothing. Pin-up beauty, runaway, Venus

of the Circus Act, nightwalker, wet nurse,

odalisque, reclining nude. The women are me

and are not only me. Ours are the only eyes.

We construct our seeing as clay or wood

into figurines of air. We perceive their shapes

and uses just as wind is seen by watching leaves.

These are the paintings I make of myself.

Art is drawn on the cave of my body.

There are as many walls inside me

as there are bones at the bottom of the sea.

It matters little how small I am in the pool

of another’s eye. It’s awe or indifference

I crave. I want to be seen clearly or not at all.

The moon is an eye flung open, useless

without a pupil. It soothes me, this not seeing.

Painters have gone blind staring at the sun.

At the center of a hurricane is an eye,

in the midst of which one believes

the storm is over. A woman’s face can break,

fall as quickly as night. Sometimes, when I cry,

all of the eyes which are mine—painted, sketched,

photographed—begin to shed blue tears. I catch them

in my hands or with pots and pans. Or let them fall

as drifts of snow. I eat them by the fistful.

When you look at me, in our most intimate

exchanges, you drape my nakedness

in a fabric I neither sewed nor bought. You pin

my beauty with a tack against the wall, or me against

a four-poster bed: thighs splayed, nipples spilling

spoiled milk. In every light, the fact of history

strips me blue. These are the conditions. The point is

to go on. Drawing myself, as water from a well,

I can no longer believe in an innocence

that was never mine. It is impossible to draw

a self-portrait without the other women figured

onto my flesh like barnacles fixed to a gray whale.

I am rough to touch. I am the yellow song

of a blue pain. The women and I walk

a tightrope of night. Our eyes adjust to growing

darkness. We make of our vision: knowingness.

It’s love the women and I make. Love fashions

our sight. We drink from the Waters That Were

Once Snow. We are quenched and we are thirsty.